Domitian was the younger son of Vespasian, and brother of Titus – he inherited power after the death of his brother in AD 81. Domitian is remembered for his strong tendency toward absolutism: he obtained full control over the Senate, reducing its role to the administrative one. Demonstrating his disdain for the Senate, Domitian used to come there in the garb of a triumphator, with a laurel wreath, a scepter and a crown, accompanied by 24 lictors. Domitian was the first to call himself “dominus et deus” (lord and god) and he strongly reinvigorated the imperial cult.

Despite his disdain for the aristocratic elite, Domitian was an able administrator: during his early years he governed the State with prudence and intelligence, while the taxation was strict but fair. Domitian’s foreign policy was also prudent: after military campaigns led earlier by himself and by his father, he strive to protect and consolidate existing borders. Until AD 88 Domitian internal policies were moderate, but after a failed revolt of AD 89, Domitian began to pursue a very harsh policy. In the last three years of his reign, from 93 to 96, real terror reigned in Rome: trials for state crimes were revived and the property of those executed went to the treasury.

Domitian had no children, which further increased his suspicion. Each failed conspiracy was followed by new executions, which in turn generated new plots. Eventually the emperor’s wife, Domitia, sensing the danger to herself, conspired with two prefects of the Praetorian Guard, which led to Domitian’s death.

During the later years of his reign Domitian conducted costly military campaigns, but he also undertook the construction of major structures in Rome, including the Capitoline Temple of Jupiter, the Temple of Jupiter the Guardian in the Quirinal, and his own magnificent Villa Alban near Rome.

In this post we will review some of the major building projects of Domitian in Rome – information about these monuments comes from our TimeTravelRome Mobile App. We will also make a virtual tour of an exceptional exhibition dedicated to Domitian, which can be visited now at the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden. The review of the Exhibition was prepared by Michel Gybels who attended the exhibition in early March 2022.

1/ Domitian and Rome

- Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus

The presence of a temple to Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the southern peak of the Capitoline Hill can be traced all the way back to the time of the Tarquins in the sixth century BC. The first, Etruscan style temple was dedicated in the hope it would soon become Rome’s foremost cult centre. To this end it didn’t disappoint; for it was at the Capitoline’s Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus that the Romans performed some of their most important religious rites and rituals.

It was here that magistrates would come to divine whether or not it was auspicious to undertake an upcoming military campaign. Should it be deemed so, and should they be successful in their undertaking, it was here they would return at the climax of their triumphal procession to offer sacrifice to their chief god. The texts known as the Sibylline Oracles were also kept here until they were mostly destroyed—along with the temple that housed them—in the fire of 83 BC. After that, Augustus had them copied and transferred to his Temple of Apollo on the Palatine.

La maquette de Rome à l’époque de Constantin (306-337) réalisée par Italo Gismondi entre 1933 et 1937. By Jean-Pierre Dalbéra from Paris, France – Maquette de Rome (musée de la civilisation romaine, Rome), CC BY 2.0.

Quintus Lutatius Catulus rebuilt the temple in 69 BC, earning himself the nickname “Capitolinus”. And he rebuilt it well enough that Caesar’s assassins were able to barricade themselves inside it 25 years later on the Ides of March 44 BC. The temple wasn’t strong enough to survive the fire of 69 AD, however, when clashes from the civil war known as the Year of the Four Emperors spilt over into the city’s streets. The war’s ultimate victor, Vespasian, rebuilt the temple in 75 AD. But five years later, during the reign of his son Titus, yet another fire consumed it along with many of the city’s structures.

Titus’s brother, the Emperor Domitian (81 – 96 AD) rebuilt a fourth and final Temple of Jupiter that would last for the rest of antiquity. Its material outlasted its purpose, however; and Christianity’s rise and paganism’s fall culminated with Theodosius’s edict closing all pagan temples in 392 AD. From this time on, the temple’s structure was opportunistically picked at and recycled until the sixteenth century, when Giovanni Pietro Caffarelli built his family palace in situ, using all remaining material possible.

What little that survives of this monumentally important temple, namely its foundations and part of its altar, can be seen behind the Palazzo dei Conservatori, within the Museo Nuovo Capitolino, and on the Via del Tempio di Giove. Remarkably, however, these are the cappellaccio base remains of the sixth century original rather than any of the subsequent reconstructions. Using these as a basis, we can estimate its size to have been around 53 by 63 metres.

Cockerell, C.R.; Imaginary view of the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, Rome; Credit line: (c) Royal Academy of Arts / Photographer credit: Prudence Cuming Associates Limited

Each within a separate cella in the temple would have stood ornate enormous statues of the Capitoline triad: Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva. Unsurprisingly none of the originals have survived the centuries. But the Jupiter of Otricoli in the Vatican Museums offers us a good idea of what the gold and ivory (chryselephantine) statue of Jupiter might have looked like.

- Rome Domus Augustana – Palace of Domitian

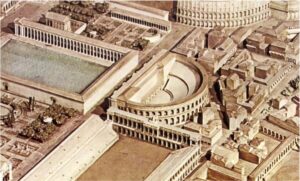

Serving as the emperor Domitian’s private (as opposed to official pubic) palace, the Domus Augustana formed part of an enormous 40,000 square metre palace complex covering the entire south-eastern side of the Palatine Hill. The complex, which we now divide up as (from West to East) the Domus Flavia, the Domus Augustana and the Stadium, was designed by Rabirius: Domitian’s prized architect and the man who deserves most of the credit for the emperor’s impressive and prolific architectural legacy. In antiquity, the complex as a whole was known as the Domus Augustana. It derived its name from Domitian’s wish to establish continuity to the first emperor Augustus. But it’s more than likely that it also comes from the original modest House of Augustus being subsumed within the Domus Flavia. The complex was completed in 92 AD—four years before Domitian’s assassination.

Palatin, localisation des différentes sections du palais impérial, By Cassius Ahenobarbus – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

The interior décor made a dramatic break from past tradition. Domitian manipulated space within the Domus Augustana to create a more sensory experience, pouring light from different directions into rooms of various shapes and sizes to disorientate his visitors. Among its many rooms were many private ones for the emperor’s sole use. To these the emperor would often retreat, according to Pliny the Younger, driven “by his fear, pride, and hatred of mankind”. In fact, such was Domitian’s paranoia towards the end of his reign that he lined the walls of the palace’s portico with the selenite (phengites lapis), allowing him at all times to see the reflection of whoever might be approaching him.

Fresco with scenes from the Trojan myth. Domus Transitoria, under the triclinium of the Flavian palace. By ArchaiOptix – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

One visitor to Domitian’s palace was Apollonius, whose biography vividly describes the Hall of Adonis where he was greeted. The passage describes baskets of brightly coloured flowers growing in abundance, and the walls of the palace painted with garden scenes. Trajan would inherit the palace once the Flavian dynasty came to an end with Domitian’s assassination. He would make it, according to his panegyrist Pliny the Younger a “safer and happier place” (tutior… securior). After Trajan, it would go on to be the residence of almost all successive emperors.

Ruins of the Domus Augustana on Palatine Hill viewed from the Piazalle Ugo La Malfa, By Jean-Pol Grandmond – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Though little of the palace’s former splendour remains, there’s still enough to see. You can’t get down to the lower level, but from the floor above you can see the peristyle courtyard with fountains and crumbling walls that would have once been awash with coloured marble. In 2007 a vaulted cavern was discovered beneath the palace which some are calling Lupercale: supposedly where the she-wolf suckled Romulus and Remus.

- Rome Domus Flavia – Flavian Palace

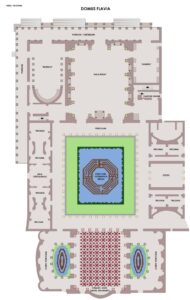

As part of Domitian’s enormous Domus Augustana complex, the Domus Flavia served as the public (as opposed to private) area of the emperor’s residence. It stands at the northwestern section of the palace complex—connected to the emperor’s private Domus Augustana to the southeast—and was the first part of the palace to be completed in around 92 AD. The Domus Flavia is made up of several large sections. The poorest preserved is the Basilica, a reception area in which the emperor would attend to his judicial duties and which also housed a detachment of Praetorian Guard. North of the palace’s peristyle is the aula regia, or regal hall, where the emperor would receive his guests and petitioners while sitting, resplendently dressed, in his apse. Then there is the cenatio: the second largest room in the palace where the emperor wined and dined his guests in an incredibly luxurious setting amongst friezes, statues and even an underground heating system. We can attribute the design of the Domus Flavia to Rabirius, the foremost architect at Domitian’s court.

Domus Flavia in Palataine Hill in Rome. By Krzysztof Golik – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Centuries of exposure to plunderers and the elements have reduced this once magnificent palace to a crumbling shell of its former self. That said there’s enough to get a sense for what it was. The peristyle that makes up the centre of the Domus Flavia and surrounds the restored octagonal fountain might be a modern restoration, but it does retain traces of white and Numidian marble on its columns and porticoes. The vaulted ceilings of the Aula Regia might be gone, along with magnificent statues that would have lined the room’s niches, but the sheer size of the room pays testament to the number of visitors the emperor would have been expected to receive. Artefacts found on the site of the Domus Flavia (and on the Palatine in general) can be found inside the Palatine Museum.

Pianta della Domus Flavia di Domiziano. By Cristiano64 – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Rome Ludus Magnus – Gladiators Training School

“Built by the Emperor Domitian (81 – 96 AD) while the finishing touches were being put to the Colosseum, the Ludus Magnus was the largest of four training schools situated in the vicinity of the enormous Flavian Amphitheatre. Though dwarfed by the structure it served, the Ludus Magnus was a huge facility: even its relatively modest amphitheatre as big as any other in the Empire.

The Ludus Magnus was a truly multipurpose facility. Not only was it the place where the Colosseum’s gladiators would train, but it was also where they resided. Along each of its sides were fourteen cells, each of which would have been the living quarters of anywhere up to five men. Considering that the structure was probably three-storeys tall, this shows just how many gladiators it was built to accommodate.

But more than just its gladiators, the Ludus Magnus was also the workplace of administrative officials, trainers, and cooks, as well as the place where gladiators would receive (rather primitive) medical care or—if that didn’t work—be stripped of their armour and possessions and prepared for burial. The Ludus Magnus led to the Colosseum through a large tunnel, parts of which were discovered during excavations of the site.

Roma, Museo della Civiltà romana: plastico del Ludus Magnus. By Lalupa – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

The Ludus Magnus was only rediscovered during the time of Benito Mussolini in 1937. The Second World War got in the way of its excavation, and the surviving northern part of the complex wasn’t brought to light until 1961 (the southern section, which we can reconstruct using the marble Severan Plan, still belies the area between Via di San Giovanni and Via dei SS. Quattro Coronati).

The most visibile remains of the three-storey brick building are the fourteen rectangular rooms on its northern side, originally used to house the school’s gladiators. You can also make out the unusual presence of a small amphitheatre where the gladiators used to train, the other half of which continues beneath the modern street level, and remnants of its cavea (seating area), big enough for around 3,000 spectators.

The Ludus magnus in Rome: barracks for gladiators built by Emperor Domitian (81–96 CE), view from Via Labicana. By Jastrow – Own work, Public Domain.

- Stadium of Domitian

Built around 86 AD by Emperor Domitian after the devastating fire of 79 AD, the stadium virtually occupied the heart of the Campus Martius and was the first permanent location for athletic competitions after the Greek models. With its typical U-shape, the stadium was 275 m long, 106 m wide, and 30 m high and its terraces could seat around 30.000 people. The inner structure was built with bricks and concrete while the exterior was in travertine, the arches rested on travertine pillars with Ionic semicolumns. Entrances opened in the middle of each long side but the triumphal gate was on the curving short end, preceded by a colonnade with marble columns. In the thirties, excavations also brought to light some of the magnificent marble decoration of the stadium. Mostly used for the athletic contests during the first centuries of the Empire, the stadium lost its function in Late Antiquity, and its arcade began to provide shelter for the poor. Gradually new buildings grew on the Roman structures incorporating them yet preserving the U-shape.

Maßstabgetreues Rekonstruktionsmodell (1:100) vom Stadion des Domitian (Nordseite) um 86 n. Chr. By Rabax63 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

The modern “Piazza Navona” sits exactly over the arena of the Roman stadium, reflecting its peculiar outline. The travertine arches of the curving end are still visible under the I.N.A. Palace, but other remains of the stadium could be seen in the basements of the private buildings overlooking the Piazza. Part of the underground archaeological area is now open to the public at given hours (https://stadiodomiziano.com). The ninth-century church of “Santa Agnese in Agone” was also built over the stadium, allegedly on the very spot where the Christian woman died as a martyr in 304 AD. The famous “Pasquino”, now set at the corner of “Palazzo Braschi” in the near “Piazza di Pasquino”, was probably one of the sculptures adorning the stadium. It is a copy of a Hellenistic statue group representing Ajax carrying Achilles’ body.

Piazza Navona Underground: Ruins of Stadium of Domitian. By Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China – Piazza Navona Underground: Ruins of Stadium of Domitian, PDM-owner.

- Rome Odeum – Odeon of Domitian

“Inaugurated around the same time as the Certamen Capitolinum (quadrennial games in honour of Jupiter) Domitian’s Odeon was the first of its kind in Rome, and was built in close proximity to his famed Stadium, the shape of which is now taken up by Piazza Navona. The Odeon’s chief architect, Apollodorus of Damascus, designed it to accommodate up to 10,000 spectators, who would come mainly to watch musical performances but would also play audiences to concerts, lectures, and political meetings. Its structure was semi-circular, resembling a Greek theatre. And it was the object of admiration for contemporaries and later visitors alike: the fourth century AD writer Ammianus Marcellinus counted it among the architectural wonders of the city (alongside the Pantheon, Pompey’s Theatre, and Domitian’s Stadium) while a fourth century writer described it as one of the seven wonders of the ancient city.

Campus Martius – Odeum of Domitian. Public Domain.

Sadly all that remains of Domitian’s magnificent structure is a single cipollino column that perhaps formed part of the scaena. It’s a sorry sight: standing in the centre of the cramped Piazza dei Massimi and almost permanently surrounded by cars. But you can at least make out the shape of the stadium’s stands from the façade of the sixteenth century Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne’s that now stands atop the Odeon’s former site on Corso Vittorio Emanuele.

- Castra Albana (Albano Laziale) – Domitian Villa

The Villa of Domitian is a palace built in the Alban Hills just outside Rome by the emperor Domitian in the first century AD. This vast and luxurious villa was the grandest of many lavish homes built by Roman patricians around Lake Albano on the site of the legendary city of Alba Longa. Domitian completely remodelled existing imperial residences visited by previous emperors and combined them into one huge new estate. New features included a nymphaeum, a racecourse and a theatre. Another feature was a long tunnel excavated to allow the emperor an easy walk to enjoy a fine view of the lake below.

Ruins of the ancient Roman theatre (part of the villa of Emperor Domitian). By Gugganij – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

The villa was little used by Domitian’s successors, although some alterations were made under Trajan and Hadrian. Marcus Aurelius stayed at the villa for several days during a period of civil unrest in AD 175. The villa was abandoned by the fourth century, when the property is reported to have been donated to the Church.

The ruins of the villa, which are located on three terraces, are today mostly enclosed within the Castel Gandolfo estate. Among the best preserved structures are the nymphaeum, the cryptoporticus (a long stone passageway that served to support the front of the terrace above) and the theatre, which still bears much of its stucco decoration.

The cryptoporticus of the Villa of Domitian in the gardens of the Papal summer residence of Castel Gandolfo. By Gugganij – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

2/ Domitian Exhibition

The exhibition in the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities (Leiden) is open until the 22th of May 2022 and it is called “God on Earth: Emperor Domitian”. The exhibition is exceptional by the quality of artefacts on display. Many objects were contributed by such major institutions as JP Getty Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Vatican and Capitoline Museums.

We present below a few highlights from this exhibition, illustrated and commented by Michel Gybels, who attended the exhibition in early March 2022.

- Portrait bust of Domitian

This realistic portrait of Domitian shows the emperor with a youthful appearance, although it was probably made late in his reign. Domitian looks with a serene gaze and has a long neck. His receding hairline is covered by a tight line of neatly styled curls.

Collection: Capitoline Museums (Rome), Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali, inv. MC 1156. Dimensions: 53 x 26 x 21 centimetres. Material: Pentelic marble. Period: 81-96 A.D. Location: Rome, Esqueline, Via Principe Amedeo. Photo by Michel Gybels.

- Relief from tomb

This fine relief decorated a tomb that was discovered in 1848 on the Via Labicana, near Rome. It belonged to the family of Quintus Haterius Tychicus, a public building contractor under Emperor Domitian. His work is proudly displayed on the relief: five Domitian buildings immortalised in stone. They were all built or restored by Tychicus.

Collection: Vatican Museums, Gregoriano Profano Museum, Vatican City. Dimensions: 43 x 163 x 24 centimetres. Material: marble. Period: 100-120 A.D. Source of the photo.

From left to right:

– A three-arch arch, probably the monumental entrance to the sanctuary of Isis on the Campus Martius (Iseum Campense), restored by order of Domitian after the fire of 80 AD.

– The three levels of the Flavian amphitheatre

– A second and a third arch, of which one is not sure which ones they are: they may be the Arch of Titus in the Roman Forum and an arch at the end of the Via Sacra, which would have marked the entrance to Domitian’s palace.

– On the far right is the temple of Iupiter Stator, also placed on the slopes of the Palatine.

- Bracelets

Suetonius wrote biographies of the first twelve Roman emperors in 120 AD. They are depicted on the coins in this bracelet from the 19th century. On one side, you can see Julius Caesar and the Julian-Claudian emperors: Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula and Nero. On the other side are the emperors of the ‘four emperor year’ 68-69: Galba, Otho, Vitellius and the Flavian emperors: Vespasian and his sons Titus and Domitian.

Collection and photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, gift of C. Ruxton Love Jr., 1967). Dimensions: 19.7 x 2.4 centimetres. Material: gold, amethysts. Period: ca. 46 B.C.-96 A.D. Source of the photo.

- Julia Titi

Julia was Domitian’s mistress and is depicted here with her typical hairstyle: an upturned head of curls. The deeply drilled holes create a light-dark effect in the marble: typical of the Flavian sculpture style. Minuscule traces of paint suggest that the curls may originally have been coloured red, but they may also have been a red undercoat for gilding. The statue was decorated with gold earrings and a diadem, inlaid with gold, silver or precious stones. A chain was attached to the small holes next to her neck.

Collection: The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu. Dimensions: height: 33 centimetres. Material: marble with paint residues. Period: 90 A.D. Source of the photo. Own work by Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Soldier

This soldier belongs to the twelfth legion: XII Legio Fulminata, which gave Titus the victory in Judea. It was part of a relief with soldiers, from the first ‘Arch of Titus’, on the Circus Maximus. It was paid for by the Senate and inaugurated in 81 AD, after Titus’ death.

The Arch of Titus was the first to be built not as a passage through the city walls, or as an entrance in a fortress wall, but rather as a picturesque setting on the axis of the Circus Maximus. It was the first arch with four fully rounded columns at the front.

Collection: Rome, Capitoline Museums, Palazzo Nuovo (depot). Dimensions: 22 x 14 centimetres. Material: marble. Period: 61 A.D. Location: Rome, Circus Maximus, excavated remains from the arch of Titus. Photo by Michel Gybels.

- Wheat measure

This corn measure (a modius) was found in the Roman fort at Carvoran, along Hadrian’s Wall. The object was used to measure grain for tax purposes. The indicated capacity (the weekly grain ration of a soldier) was smaller than what actually went in, so the taxpayer was in fact cheated. It is an extremely rare find: not only in the province of Britannia, but in the entire Roman Empire.

The inscription on the modius should read: “In the fifteenth consulate of Emperor Domitianus Caesar Augustus, Germanicus tested the capacity of 17 ½ sextarii; weight 38 lbs”. The name ‘Domitian’, however, was erased after the death of the emperor and his damnatio memoriae in 96 A.D. In about forty per cent of the four hundred surviving texts and inscriptions on Domitian, such a thing happened.

Collection: Chollerford, Hexham Clayton Museum, Chester’s Roman Fort and Museum Hadrian’s Wall. Courtesy English Heritage Trust/ The Trustees of the Clayton Collection. Dimensions: height: 29 centimetres, diameter at bottom: 30.5 centimetres. Material: copper alloy. Period: 90-91 A.D. Location: Carvoran (England), Roman fort. Photo by Michel Gybels.