Written for TimeTravelRome by Kieren Johns.

All roads lead to Rome, or so the old proverb goes. For those of us with an interest in the ancient world, it’s a saying that still very much rings true to this day. Whether it’s a chance to explore the remains of the ancient city itself in the Forum, or the opportunity to get up close and personal with the masterpieces of ancient art in the city’s many museums, there is more than enough to keep you interested for days and weeks – and probably longer!

We’ve previously explored 5 of the best sites in the north of Italy, so now we turn our attention to the south. Away from the ancient capital of Empire, there was an eclectic mix of cultures in Italy, as expanding Roman influence mingled freely – though not without controversy and conflict in some instances – with the Hellenic cultures that had been brought to Italy via Greek colonisers, whilst the influences of the Near East and North Africa were never far away either.

Below are 5 of the best sites to explore in the south of Italy.

1. Capua

Just to the south of Rome in the Campania region, the ancient city of Capua was founded – at best estimates – in around 600 BC. This is based on assertion of Cato the Elder, the staunchly conservative senator of the 3rd century BC, who also claimed that the city was founded by the Etruscans. Roman influence in the region began in earnest in around 424 BC, when the Etruscans settled here sought Roman assistance against the invading Samnites.

This connection was confirmed by 312, then Capua was connected to the city of Rome itself by the Via Appia, which leads south-east out of the capital. The prominence of the city grew significantly, and by the period of the Second Punic War (218-201 BC) it was able to put significant forces into the field for battle. Originally allied to Rome, the great victory of Hannibal at Cannae in 216 BC – in which he inflicted one of the worst defeats of Roman history – prompted the Capuans to renege on their oaths to Rome and ally with Carthage. Such was the prominence of the city, that Hannibal and his men actually wintered in the city.

Of course, the Romans eventually drove the Carthaginians out of the Italian peninsula, and after this war of attrition, those who had allied with Hannibal were punished severely. Capua was no different, and following a length siege, the city was captured by the Romans in 211 BC and made an example of; its magistrates were abolished, the lucky inhabitants who survived were deprived of their civic rights, and its territory was declared to be a Roman possession.

Despite these political hardships, Capua remained wealthy. This was in part thanks to agriculture – the region was excellent for growing spelt, which had a variety of uses – whilst it was also a centre for the manufacturing of bronze. Historians, including Cato the Elder and Pliny the Elder have attested to the quality of the Capuan wares in the highest terms. Accordingly, the city remained a by-word for opulence. It features scarcely in the historical record of the imperial period; it expanded as a colony from Julius Caesar onwards, growing in size again under Mark Antony, Augustus, and Nero. It evidently remained significant, if inconspicuous, in the late antique period, with the 4th century poet and rhetorician Ausonius including the city as part of list of major Roman cities in the Ordo urbium nobilium.

DID YOU KNOW?: The poet Ausonius, who lived during the 4th century AD, produced a poem – the ordo urbium nobilium – to commemorate a journey he had taken through the Roman empire in around AD 390. Listing the top 20 most important cities in the Roman Empire, it places Rome as number 1, with Constantinople and Carthage tied in second. Capua comes in at number 8, whilst, of course, Ausonius’ native Burdigala (Bordeaux) has a place in the list, finishing at number 20. We wonder how many stars Ausonius would have given the cities on the TimeTravel Rome app?

Visitors to the modern city of Capua are unfortunate in that there are no pre-Roman remains to explore. However, a wealth of smaller material from this era has been recovered, notably from tombs that date from the 7th to 5th centuries BC. These have included frescos, bronze artworks, and even in some instances, inscribed votive offerings that have preserved Etruscan script! Across the city, evidence of Roman antiquity is everywhere visible, including the remains of the so-called Arch of Hadrian. This originally marble clad, 3-bayed arch (now, only two survive), spans across the route of the Via Appia itself.

The Arch of Hadrian spanning the Appian Way, Northern side, Capua. By Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0,

Elsewhere in the city are the remains of the thermae and an Augustan era theatre. For those interested in the syncretism of Roman religion, it is possible to visit the city’s mithraeum, a subterranean place of worship, dedicated to the eastern deity Mithras (identifiable by his pointed Phrygian cap, and known to have been worshipped all over the Roman Empire from the 3rd onwards).

Mithraeum – Santa Maria Capua Vetere. By Danilovarphotos – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Located outside of the modern city, the standout monument of Capua is the ancient amphitheatre. This arena, originally built by Augustus but restored by Hadrian and dedicated by Antonius Pius, was the second largest in the Empire, behind only the Colosseum itself. It should come as no surprise to hear that Capua was famous for its gladiatorial training schools, and indeed, it was here in 73 BC that the revolt of Spartacus first started! Although much of the building material has since been spoliated (reused) in the medieval period, visitors today still gain a great insight into the size of the arena and a sense of the spectacles that must have unfolded here.

Inside the amphitheater of Santa Maria Capua Vetere. By Dom De Felice e Carla Nunziata – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

2. Sperlonga

Located just to the south of Rome (but still in the Latin province), the coastal site of Sperlonga is a by word for imperial opulence. Located between the Via Appia and the Pontine Marshes. It was originally the site of a sprawling Republican-era villa but the land soon came into the possession of the emperor Tiberius, who also took ownership of the famous grotto at this site. It was inside this grotto that the emperor Tiberius – known for his appreciation of fine art, as evidenced by the infamous Apoxymenos anecdote (see Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 34.61-2) – created perhaps the most elaborate dining room in Roman history. The emperor converted this natural opening in the coastal cliff as a magnificent triclinium, or dining room.

Villa of Tiberius (Sperlonga). By Sailko – Own work, CC BY 3.0.

The most famous feature of the emperor’s dining room decorative scheme were the Sperlonga sculptures. These sculptures, in the ‘Baroque’ Hellenistic style but believed to date to the early imperial period, depict scenes from Homeric mythology. Perhaps the most iconic statuary group from Sperlonga, the Blinding of Polyphemus, shows the hero Odysseus and his trapped men driving a red hot spear into the eye of the cyclops Polyphemus.

The Blinding of Polyphemus, cast reconstruction of the group, Sperlonga. By Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

It was not merely the artworks here that offered drama. In AD 26 the grotto collapsed, almost crushing the emperor to death. The historians Tacitus (Annals, 4.59) and Suetonius (Tiberius, 39) both provide narratives of this imperial near-miss. According to Tacitus, the emperor’s life was actually saved by the courage of Sejanus, who would go on to wield terrible influence over him. Similarly, not all who were present in the grotto were fortunate enough to escape unscathed; several died.

Sperlonga ruins of the Tiberius villa. By steveilott – Flickr: Sperlonga, CC BY 2.0.

Visitors to Sperlonga today are presented with the opportunity to explore the wealth of this former imperial residence thanks to the museum that now occupies the site of the former villa. Within the museum there are, of course, the remains of the statuary groups. Naturally, the statues suffered significant damage during the collapse of the grotto in antiquity, so elements are missing in places. Nevertheless, they remain inescapably dramatic and a must-see for those interested in ancient art and mythology.

3. Minturnae

Situated in southern Lazio, straddling the Liris river on the coast between Rome and Naples, the town of Minturnae (now, Minturno) was a prominent ancient settlement on the ancient Via Appia. The site was originally settled by the Ausones, a native people who inhabited the central and southern regions of the Italian peninsula. During the last decade of the 4th century BC, the site came under the influence of Rome. First described by Livy (ad Urba Condita, 8.10), it was captured by the Romans in 313 BC after a particularly violent confrontation, and a mere two years later it was connected to the nascent imperial capital by the Via Appia. By the year 296/5, a full Roman colony had been established here.

Overview of Minturnae, Minturno, Italy. By Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The colony grew in stature and significance, and archaeological evidence indicates that it underwent a process of fortification that coincided with the Second Punic War in the late 2nd century; it appears a great tufa wall was built around the site to protect it from Hannibal’s armies. The city appears to have remained prominent throughout the imperial period but lacking political importance. It developed over the course of the imperial period, with Augustus and Tiberius settling additional veterans here, whilst the emperors were also responsible for furnishing the city with several of its most notable monuments, the remains of which continue to be impressive to this day.

DID YOU KNOW?: According to the ancient biographer Plutarch, the Republican general Marius had a lucky escape from the agents of Sulla at Minturnae. In his Life of Marius 37-40, there is a description of the hero’s flight, naked through the muddy marshes nearby, his plight in the town which condemned him to death, and his eventual escape to the island of Aenaria.

The remains of antiquity at Minturnae testify to a wealthy and prominent ancient settlement. Today, visitors can explore an excellently preserved theatre, which once would have seated around 4,600 spectators. Intriguingly, the northern wall of the ancient Forum of Minturnae appears to have served as the scaena of the theatre, whilst it archaeologists have discovered that the cavea – the seating area – was built seemingly atop the defensive walls built to confront the Hannibalic threat. The substantial remains of an aqueduct from the 1st century, with its distinctive opus reticulatum brickwork, are also impressive.

The Roman theatre, view on the temples and Republican & Imperial forums. By Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

4. Tauromenium

In the east of the island of Sicily, the ancient settlement of Tauromenium (Taormina) – situated between Messana to the north and Catana to the south – predates the arrival of the Greek colonists to the island. Greek colonists arrived on the island in the latter decades of the 8th century BC, establishing a city named Naxos; it is believed that Tauromenium was founded by colonists from his city, as is described by the 1st century AD geographer Strabo.

Unlike other Greek colonies on Sicily, Tauromenium was notable for the good governance it reputedly enjoyed. Andromachus, who was the father of the historian Timaeus (whose work has survived only in fragments unfortunately), was notable for the clemency and good governance of his rule. Andromachus is known to have welcomed Timoleon into the city when he arrived on the island in the mid-4th century BC (ca. 345). This proved to be a sensible choice by Andromachus; after Timoleon had expelled the other tyrants from Sicily, the ruler of Tauromenium was allowed to retain his authority, which he did until his death.

Passing into Roman control with the subjugation of the island, a suggestion gleaned from Appian, Sicily and the Other Islands, 5 is that the town submitted readily on favourable terms to the Roman general Marcus Marcellus. Accordingly, it enjoyed a favoured status in Roman politics. It enjoyed the privileges of a civitas foederata – an allied city. This meant that it enjoyed a degree of independence and escaped the burden of furnishing the fledging Empire with ships when obliged (the fate of Messina for instance). Nevertheless, the city suffered extensively during the Sicilian Servile War (134-132 BC), when it endured a lengthy siege. The city remained sizable though largely unimportant during the imperial period.

DID YOU KNOW?: During the imperial period, Tauromenium became famous for the quality of its produce. Pliny the Elder reports on the quality of its wines (Natural History, 14.6.8), whilst the satirist poet Juvenal, writing in the late 1st century AD records that that coastal waters at Tauromenium offered up some of the choicest mullets for the dinner tables of Roman elites. The late 2nd century rhetorician Athenaeus similarly records that the city was valued for a particular type of marble. Tauremenium evidently enjoyed a long-standing reputation as a place for life’s fineries!

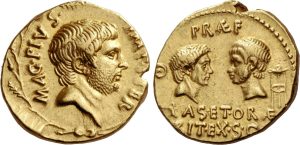

The city played a prominent role in the wars of Sextus Pompeius, the son and heir of Pompey the Great and adversary of Octavian as he sought to cement his rule over the Roman world. The strength of the city’s fortifications prompted the renegade admiral to make this one of his main defensive locations. It was also one of the sights when the future emperor took to the field himself; in a naval engagement here Octavian and Sextus engaged in a battle that resulted in the almost total annihilation of the latter’s forces. Following his defeat, Octavian nominated Tauromenium as one of the cities to receive a Roman colony, a clear precautionary tactic.

Sextus Pompeius. Aureus, struck in Sicily 37-36. Obv: Bearded and bare head of Sextus Pompeius. Rev: Heads of Cn. Pompeius Magnus on l., and Cn. Pompeius Junior on r., facing each other. Numismatica Ars Classica Auction 99. Picture used by permission of NAC.

Today, the ancient city of Tauromenium has been incorporated into the modern town of Taormina. Scattered remains of antiquity are present all over the site. The most prominent site remains the ancient theatre. The remains of this structure are mostly brick-built, indicating that they are Roman in date. However, the plan and arrangement are Greek in style, meaning that it is highly likely that the structure standing today was built atop the remains of a much older theatre complex. The theatre is actually the second largest of any in Sicily, further indicating that Tauromenium remained a site associated with luxury and good living in the imperial period.

The ‘Teatro Greco’ at Tauromenium. The Roman-era brick work is identifiable here in the scaena frons, whilst the Sicilian vista beyond is beautiful. In the background, the slopes of Mt Etna are visible.

Greek Theater – Taormina. Looking toward the south over Gardini-Naxox. By Evan Erickson – Own work, Public Domain.

5. Amiternum

Located in the Province of Abruzzo in the east of the Italian peninsula, the site of Amiternum was once a thriving Sabine city. Its location at the head of the upper Aterno valley meant that it was one of the most important cities in Sabinium. Although details of its Sabine history are hazy at best, it was obviously well known in Roman antiquity. Virgil, in his Aeneid, described it as one of the most powerful Sabine cities (7.710), whilst it is also referred to in the works of Varro (Lingua Latina, 5.28), Pliny the Elder (Natural History, 3.12) and the geographer Ptolemy (3.1.59).

Amiternum amphitheater. By Ra Boe / Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0 de.

The city fell under Roman control in 293 BC, and it appears to have occupied a strategically significant location. It was once situated at the junction of four of the most important Roman roads: the Via Caecillia, the Via Claudia Nova, and two branches of the Via Salaria. It should thus come as no surprise that the city was involved in the wars of the Roman Republic, and indeed, the 1st century geographer Strabo records the city as having suffered severe damage during both the Social and Civil Wars throughout the 1st century BC. This appears to have taken its toll on the city, as the geographer suggests that it was still reeling from these damages during his own period. However, it evidently recovered. It was colonised, likely at the behest of Augustus, and grew once more in significance.

DID YOU KNOW? Amiternum was the birthplace of the Roman historian Sallust. Born in 86 BC, Sallust wrote histories that covered some of the most turbulent and important events of the 1st century BC as the Republic gradually splintered. These include The Jugurthine War, detailing Rome’s war against the Numidian King, Jugurtha, from 111 to 105 BC, and Catiline’s War, which provides the narrative of Catiline’s attempted conspiracy in 63 BC.

The remains of ancient Amiternum that are still visible attest to the significance of the city. The most impressive of these are the remains of the amphitheatre and theatre, both structures dating to the imperial period. Above these colossal edifices of Roman culture, on the hill where the village of San Vittorino now stands, there are also some walls that are believed to date to the earliest periods of Amiternum’s history, the site’s Sabine past. Here, there are also a number of early Christian catacombs.

Picture below: the 1st century BC Amiternum tomb shows the funerary procession of a former resident of the ancient city. The deceased, the central reclining figure, is mourned by his wife and children to the left, whilst trumpet and horn players to the right announce the funerary procession, the pompa.

Plate with a funerary procession, now in Museo nazionale d’Abruzzo. By Sailko – Own work, CC BY 3.0.

Excavations of the site of Amiternum have returned a wealth of smaller finds. Many of these pieces are now displayed in the archaeological museum of nearby Aquila. The most impressive find remains the Amiternum Tomb. This 1st century BC sarcophagus is known for its celebrated relief decoration that shows the Roman funerary procession – the pompa – that was so evocatively described by Polybius (History, 6.53-4).

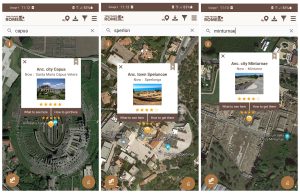

The top 5 of Southern Italy on TimeTravelRome

The TimeTravelRome mobile app features all 5 ancint sites descried above, and alse thousands of other Roman sites and monuments in Italy, Europe, Asia and Northern Africa.

Header image: Santa Maria Capua Vetere. Anfiteatro. By Miguel Hermoso Cuesta – Own work,CC BY-SA 4.0.