Written for TimeTravelRome by Michel Gybels

Description of Mithraeums – Michel Gybels & TimeTavelRome

Who was Mithras and why was this outsider in the pantheon of gods so widely venerated throughout the Roman Empire? In this article, we examine this mystery cult, which initially became popular among the legionnaires during the Roman Imperial period and how the cult forged close alliances of loyalty and brotherhood among its members.

Roman Worship of Gods

Roman worship of gods consisted of a mutual agreement between the celebrant and his or her chosen god. Offerings to the gods were made according to the do ut des principle, in other words, I give you something in the expectation that I will get something from you in return. For example, an offering of food to a god automatically brought with it the worshipper’s demand for health, prosperity and happiness. With this in mind, the construction of a temple guaranteed positive and benevolent feelings of the god, to whom the temple was dedicated, towards his worshippers. In order to ensure the flourishing of the relationship between the people and the gods, the population inside and outside Rome was also prepared to embrace any foreign deity insofar as that god could contribute to the welfare of the city, the military garrisons, the families living there and even individuals. Each section of society had specific favoured gods who could help them in case of need. Throughout the Roman Empire the people worshipped a pantheon of gods imported from other cultures. However, despite their ‘foreign’ origins, these gods were considered an essential part of the cult of the gods in the cities of the empire and were worshipped in the temples erected for them in the way that was customary for the ‘indigenous’ cult.

The Origin of Mithraism

Recent researchers, including Roger Beck, assume that the mystery cult was created in Rome by someone who had knowledge of both Greek and Oriental religion and they also assume that several principles of the religion originate from Hellenistic kingdoms where Mithras was identified with the Greek sun god Helios, one of the deities of the syncretic Graeco-Iranian royal cult founded by Antiochus I, king of the small but prosperous buffer state of Commagene in the middle of the first century BC.

The German historian Reinhold Merkelbach, on the other hand, suggests that the cult of Mithras in Rome was created by certain persons from an eastern province or border state of the Roman Empire who were clearly familiar with the Iranian myths, several details of which were woven into new degrees of initiation, and that these persons had to be of Greek origin because elements of Greek Platonism were simultaneously woven into the cult. At the same time, he suggests that the myths were probably created within the milieu of the imperial bureaucracy and were exclusive to its members.

Archaeological research also shows that only three Mithraea were discovered in Roman Syria, in contrast to the more widespread cult sites in the west. According to archaeologist Lewis Hopfe, this is clear evidence that Roman Mithraism had its epicentre in Rome, and that the fully developed religion was spread towards Roman Syria only later by soldiers or traders from Rome.

Marble Statue of the god Mithras immolating a bull 100-200 AD. Place of discovery is unknown. From the British Museum. Photo by TimeTravelRome. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The first significant expansion of Mithraism in the empire occurred quite rapidly during the reign of Antoninus Pius and under Marcus Aurelius. The cult reached its popular height during the second and third centuries of our era, the period when the religion of Sol Invictus also became part of the state religion. In this period a certain Pallas devoted a monograph to Mithras and later a certain Eboulus wrote his History of Mithras. Both works have been lost.

According to the fourth-century Historia Augusta, Emperor Commodus also took part in the mystery cult, although Mithraism never became part of the state religion.

A Mystery Cult for the Legion Soldiers

The god chosen by the Roman legionaries was Mithras. The London Mithraeum, located in Wallbrook in the financial heart of the city, was rediscovered in 1954 and is now open for visits. The original construction of the temple was a gift to the god and the followers of the Mithras cult from Ulpius Silvanus, a retired Roman officer from the third century, and remained in use for over 60 years. The remains of the temple, with numerous well-preserved statues, show that Mithras was an important deity for those who lived in what was then Londinium.

London Mithraeum. Photo by TimeTravelRome. CC BY-SA 2.0.

It was not easy to become a follower of the Mithras cult. You had to agree to follow a mystery cult anyway, which meant that the ways of worship were shielded from outsiders who were not initiated. To become a full member of the temple you had to go through seven initiation rites in the form of tests of knowledge. A potential follower also always had to be male. The final initiation baptism consisted of bull’s blood.

Membership of the mystery cult consisted of a well-defined hierarchy divided into degrees: the first degree was Corax or Raven. Ravens appear in Greco-Roman mythology and were traditionally messengers of the gods in various religions, including Mithraism. That rank was followed by that of Nymphus or the groom; Miles, the soldier; Leo, the lion (a virile motif within the hierarchy of soldiers); Perses, the Persian and Heliodromus, the messenger of the Sun. The highest position one could attain was that of Father.

The Mithraeum of Felicissimus in Ostia Antica (Reg. V, IX), Italy, contains a floor mosaic dating from the first century of our era, consisting of seven panels, one for each level of initiation. Each panel links the initiate to a specific god and a series of actions that had to be performed as part of a secret ritual.

Mithreaum of Felicissimus. By Liberliger. CC BY-SA 4.0.

The first panel, near the entrance to the entrance hall, is for the degree of the Corax. That panel shows a raven, a small bowl and a caduceus, a magic wand wrapped in a serpent like the one worn by the god Mercury. The Nymphus wears a crown in the shape of the rising moon, which links him to Venus, as well as a lamp. Miles wears a military helmet, which links him to the god of war Mars, a lance and a bag.

3rd panel – Miles. By Kharmacher – Own work, CC0.

Leo is depicted with a thunderbolt, the crest of Jupiter, a spade and a sistrum, a kind of Egyptian musical ratchet.

Mithraeum of Felicissimus – 4th panel. By Marie-Lan Nguyen. CC BY 2.5.

Perses has a rising moon, an Asiatic sword and a scythe.

5th panel. By Marie-Lan Nguyen. CC BY 2.5.

Heliodromus wears a crown with ribbons, a whip and a burning torch.

6th panel. By Marie-Lan Nguyen. CC BY 2.5.

Finally, at the end of the cult space, there is the mosaic of the Pater with a patera or small bowl for making offerings to the god, a magic wand for guiding the initiates, a Phrygian cap and a sickle.

7th panel. By Marie-Lan Nguyen. CC BY 2.5.

The initiates were collectively known as the syndexiol, which translates as those united by the handshake. The idea behind it is that that handshake seals the link between the individual and the god and his followers.

A Unique Male Alliance

This unique male alliance can be considered an extremely positive feature of the Mithras cult. It was built around the existing feelings of professional military loyalty and promoted an ideal of brotherhood between individual members and their military colleagues of equal rank. More or less the same thing we see in the Middle Ages in various military religious orders such as the Knights Templar, the Knights of St John, the Teutonic Order, the Order of Malta, etc.

By making entry to the covenant difficult and the various degrees of initiation, which raised the status of its members, it was a great honour for many to be allowed to participate in the mystery cult, which also raised their social status in society.

Remains of the Brocolitia Mithraeum at Carrawburgh on Hadrian’s Wall in northern England show that a well was built in the centre of the main building, which may have been used for the initiation of potential new members of the cult. The neophyte descended into this well where he “cast off” his former life and then “resurrected” as an initiate.

Temple of Mithras, Carrawburgh. Photo by Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Depictions of Mithras travelled with the Roman troops throughout the empire from Germany to Syria. In England alone there are three sanctuaries dedicated to Mithras on Hadrian’s Wall, namely the earlier mentioned mithraeum of Brocolitia (Carrawburgh), that of Borcovicium (Housesteads) and that of Vindobala (Rudchester). In the temples of Vindobala and Brocolitia, inscriptions in the walls show the generosity of gifts to the deity by various commanders of the regiment.

As far as Rome is concerned, the emperors Diocletian and Lucius are also known as members of the Mithras cult. This clearly indicates that high-ranking persons also joined the cult and, moreover, they considered it expedient to invest in images of Mithras (statues, frescoes, etc.) to embellish the interior of the temples. Six mithraea in England were found in military zones; the example of Londinium is therefore the only complex so far found in a civilian environment.

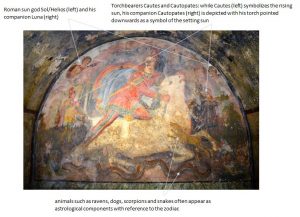

The Images of Mithras

There are numerous depictions of Mithras that have survived in Roman temples. Many show the so-called tauroctony or killing of the bull. The various elements of such tauroctony, whether depicted in stone reliefs or in frescoes, always focus on the same act whereby Mithras overpowers the bull and drives a dagger into its neck. In this heroic act, he is never alone but is always accompanied by his dog, who is often depicted on the back of the bull and at the same time biting the animal’s throat. At the same time, we also see a scorpion sticking its claws into the bull’s testicles. These two motifs are linked to the Persian god Arimanius, the bringer of death. He was the gatekeeper between the earth and the underworld and prevented the dead from gaining access to Mithras. The dog and the scorpion, in turn, ensured the quick death of the bull. In some versions, ears of corn or vines grew from the bull’s wounds. In a hymn to Mithras, found on the walls of a temple in Rome, we read among other things “you have redeemed us by shedding eternal blood”.

Marble statue depicting the tauroctony. From Rome, Sala dei Animali, Vatican museums, Rome. Photo by Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The sacrifice of the bull can therefore be seen as an act of life renewal carried out so that society would survive the winter. Remnants of paint on wall paintings of the scene have shown that the bull was white. This leads to the claim that Mithras was the sun or the representative of Sol Invictus, the sun god, who was responsible for the murder of the ever-renewing moon that took the form of a bull. During the sacrifice, the bull’s head is always turned to the right in all the images, but whether this is significant cannot be determined. Mithras himself looks at the bull and sometimes turns his gaze away over his shoulder to an image of the sun with which he seeks the approval of the sun god Sol for his act. Between Sol and Mithras also moves a raven, which can be seen as the deliverer of a message to both. The Roman version of Mithras is always a young clean-shaven man wearing a Phrygian cap, the Persian symbol of freedom, which confirms that he was born a free man and not a slave. The priest in the Mithras cult wore the same hat to emphasise his status as senior or eldest. Mithras also always wears a cape that fans out behind him. All these images were always placed or painted at the far end of the worship space in the sanctuary.

Tauroctony relief from the Mithraeum at Neuenheim near Heidelberg, with framing panels depicting the life of Mithras, Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe. Photo by Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The Anatomy of a Tauroctomy

To clarify the preceding presentation visually, here is a picture of a tauroctony, a fresco from the mithraeum of Santa Maria Capua Vetere in Italy that dates from the second century of our era. This work gives a good idea of the scenes with their various symbols and elements.

Tauroctony fresco in the mithraeum of Capua, 2nd century. Picture by Carole Raddato. Annotations by Michel Gybels.

Mithraism and Christianity

It is believed that Mithras was born from a rock, a process known as petrogenesis. His birth date was set for 25 December, around the time of the traditional celebration of the winter solstice. On the 6th January following his birth, he was visited by wise men to begin his education. The day of his worship is Sunday. Mithras lived a celibate life and was primarily concerned with hunting and battle tactics rather than family or amorous affairs, and he was also the god of light. One of his altars, at Brocolitia (Carrawburgh), shows a half figure of him with a round crown or halo on his head.

Brocolitia (Carrawburgh) Mithras altars. By Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

When we put all this information together, it is not difficult to understand why academics made numerous links with the Christian religion. It was even postulated that Christianity was responsible for the end of Mithraism. Unlike Mithraism, which was open only to male adepts, Christianity also welcomed women for the shared experience of the rite of celebrating the bread and wine, which could explain its success and certainly bring about the disappearance of the Mithras cult.

The Archaeological Evidence for Mithraism

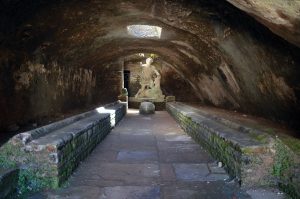

The archaeological evidence for Mithraism is mainly determined by the many depictions of Mithras found in third-century Europe. Mithraea, the temples where Mithras was worshipped and commemorated, were always rather small buildings, probably due to the exclusivity of the religion which was only for initiates. They were only big enough to accommodate a maximum of ten to fifteen men per worship. One of the few written references to Mithras can be found in the work of Porphyrius (234-305), a Neo-Platonic philosopher who was born in Tyre (present-day Lebanon). In his work On the Cave of the Nymphs he states that another name for the initiates of the cult was Persian, thus referring to the origin of Mithras, the creator and father of all things, who, according to him, was born in a cave in the mountains on the outskirts of Persia. As a result of this birthplace, it is not surprising to note that the majority of the mithraea are located in underground chambers, often with roughly hewn sections reminiscent of the rocky formations of a cave. Public events were completely forbidden in these temples, not only because of the lack of space but certainly because of the fact that only initiates of the cult were allowed to enter the sacred spaces. Even processions or offerings outside the temple were strictly reserved for the initiates and were always shielded from the general public. In short, everything happened behind closed doors. It is known that at regular intervals of the year celebrations were also organised within the Mithraic calendar.

The centre of the Mithraeum is always rectangular with a row of benches on each side. During feasts, the participants at those benches would line up for the banquet which was organised for a limited number of pre-selected people. The lowest in rank, the corvus, was the one who had to serve. In the mithraeum of Doura-Europos in present-day Syria, graffiti have been found on the walls of the temple giving an indication of the expenses of feasts, with an indication of the products used such as wine, meat and the famous garum or fish sauce to flavour the meals.

From rubbish found in a pit of the Mithraeum in Flemish Tienen, where troops were stationed, it can be deduced that chicken, lamb, pig and wild boar were also on the menu. Most of these feasts took place in June around the summer solstice. In the mithraeum of Lentia in Austria, mainly fruit pits were found. From this we can deduce that the festivals there took place during the harvest season, i.e. in June, July or August. The initiates most likely prepared their own food, as evidenced by the remains of a kitchen found in the mithraeum of Brocolitia on Hadrian’s Wall.

The cult of Mithras therefore created a unique bond between the Roman soldiers with an emphasis on like-mindedness and comradeship in places that were sometimes far from home. Throughout the Roman Empire, members of this mystery cult came together to live and share the religious experience within their community of initiates. The popularity of the cult lived on for many years until it died out in the late fourth and early fifth centuries of our era.

There is indeed no evidence for a possible continuation of the Mithras cult in the course of the fifth century. The cult therefore disappeared earlier than that of the goddess Isis. That goddess was still known in the Middle Ages as a pagan deity while Mithras was already forgotten in late antiquity.

The Archaeological Heritage

Over the years, a lot of archaeological research has been done on mithraea and several of these cult sites have been found, restored and opened to the public. Here is an overview of some sites related to the Mithras cult:

GREAT BRITAIN

- Londinium (London) Mithraeum

The temple of Mithras was built around AD 240. It would have originally been located on the east bank of the River Walbrook. It measured 18 x 8 meters and was constucted in ragstone, Roman brick

and tile. It was rendered with a smooth plaster which was likely painted. The floor was made of timber, over beaten earth and gravel, with stone stairs. Entrance was through a narthex and via stairs which led down to a central nave and then up to an apse at the rear which contained the altar. Two rows of seven columns created aisles along each side of the nave. A timber-lined water vessel was located in the southwest corner. The temple was found during construction of Bucklersbury House in 1954. Initial excavations found fine quality, 3rd century Carrara marble statues of Minerva, Mithras, Serapis, Bacchus and Mercury, as well as courser local clay religious figurines. To allow continued construction on the site in the 1950-1960s, the entire temple was relocated by 100 metres and installed in Temple Court along Queen Victoria Street. Following demolition of Bucklersbury House in 2010 the temple was returned close to its original location. Excavations in 2010 and 2014, led by Museum of London Archaeology, recovered over 14,000 artefacts from the site, including tools, pewter vessls, footwear, a large number of ancient Roman writing-tablets

Visitors in the mithraeum of London. Photo by TimeTravelRome. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The temple has been reconstructed 7 metres below street level as part of an archaeological exhibition within the new Bloomberg building. In order to preserve walls of the original temple which have not been excavated, the reconstructed temple is about 12 metres west of its original location. The temple as displayed reflects the first building phase dating to AD 240 prior to later Roman modification. The reconstruction uses the original stone and brick, however modern timber, lime mortar, and render have been used based on samples of the original Roman materials. A number of artefacts are also on display here and in the Museum of London. Additional information on the website www.londonmithraeum.com

- Mithraea on Hadrian’s Wall – Northern England

At Hadrian’s Wall in northern England, remains of three different mithraea were also found. Detailed information is available on the English Heritage website.

GERMANY

- Riegel am Kaiserstuhl

A rather modest mithraeum temple was discovered here in the twentieth century. Riegel am Kasierstuhl was the site of a Roman garrison in antiquity, with the site occupied the junction between two important routes. Considering this military presence, it is perhaps unsurprising that a mithraeum was built here; the cult, much of which still remains unknown, appears to have been particularly popular with the Roman army.

The mithraeum was built in the late second century AD, with a timber frame atop sandstone foundations. The tauroctony relief scene typical of a Mithraeum has been lost, but an altar of red sandstone was discovered, bearing an inscription to DEUS INVICTUS, the “invincible god”.

Based on archaeological evidence, the site was evidently not destroyed but rather abandoned. This itself is quite significant, as many of these temples were reused by later Christian worshippers. In Reigel itself, one can visit the site of the mithraeum, where the foundations of the temple are still in place and clearly marked out. A replica of the altar is also positioned here. Unfortunately, the tell-tale mark of a Mithraeum, the tauroctony relief showing Mithras (in distinctive pointed Phrygian cap) slaying the bull has been lost.

The small artefacts recovered from the site, including the original red sandstone altar, recovered from here are now displayed in the Archäologisches Museum Colombischlössle in Freiburg im Breisgau.

Mithras altar in Riegel. By Dr. Eugen Lehle. CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Mithraeum in Neustadt an der Weinstraße

The temple of Mithras in Neustadt was, according to an inscription found here, constructed in AD 325, making it possibly the last Mithraeum to be erected anywhere in the Roman world. Ultimately, it was largely destroyed when replaced by a Christian church.There is little to see at the site itself, apart from a replica of a Mithras cult relief, but important relics recovered from the temple, including an altar, are now preserved in the Historical Museum of the Palatinate in Speyer.

Mithras relief, now in the Speyer Museum. Photo by Von Haselburg-müller. CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Mithraeum in Königsbrunn

Various Roman structures have been identified in the Bavarian town of Königsbrunn, including a Mithraeum that was originally part of a rustic villa complex. It appears to have been made largely of wood and to have had painted walls. The foundations of the structure have survived and are now protected from the elements in their own building. On one of the walls is a Mithras stone recovered in the sixteenth century from a cave in the South of Tyrol. Nearby, stones laid on the ground indicate the layout of a public bath. Smaller finds from these sites and others in the region can be seen in the local archaeological museum in Königsbrunn.

Mithraeum in the Königsbrunn Museum. Photo by Von Flo Sorg. CC0.

- Col Aug. Treverorum (Trier) Mithraeum

The cult temple to Mithras was built within the Sanctuary of Altbachtal in the 4th century. The Mithraeum was built into the basement of a private home of an elite cult initiate, Martius Martialis, who held the rank of pater. The site was excavated between 1926 and 1934. Excavators found a large number of terracotta and stone votives dating to the 4th century. In particular, a famous stone relief depicting Mithras’s rock-birth was found at the site in 1928. It was found in-situ at the west end of the Mithraeum between two limestone altars and served as the main cult image for the temple. The relief measures 94 x 50 cm with a thickness of 15cm. It shows two temple columns supporting a tympanum. In the centre of the columns, Mithras is shown being born from the rock and surrounded by the four winds. He carries a globe and a circle showing the six signs of the zodiac. Looking on are Sol, Luna, a lion, raven, serpent, and a dog. The stone altars are inscribed with dedications by Martius Martialis.

There are no visible remains of the Mithraeum or the surrounding Sanctuary of Altbachtal. The Mithraeum was destroyed during the late Roman period. The stone relief of Mithras’s rock-birth and other cult images from the temple are on display in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum.

Mithras relief from Altbachtal now in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum. Photo by TimeTravelRome. CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Halberg Mithraeum

Situated on the Halberg slopes on the German border with France (near to the city of Saarbrücken), there are the evocative remains of one of the ancient Roman mystery cults. This is a Mithraeum (a Mithrasgrotte or Heidenkapelle in German). The Roman residents of the area, which was formerly in the area below the Halberg, carved this sanctuary into the rock face here, where they worshipped the god Mithras. Usually associated with the soldiers of the empire, Mithras was typically worshipped in secluded, subterranean places such as this.

This mithraeum follows the plan of many of the Mithraea known throughout the Roman world: a three-aisled space, with benches for worshippers on both the left and right. At the end of the central aisle there would have been a depiction of the tauroctony, the iconic scene of Mithras (identified by his pointed Phrygian cap) slaying the bull.

The Mithraeum in Halberg near Saarbrücken. Photo by Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Archaeological evidence from the site suggests that this Mithraeum was used predominately during the second half of the 3rd century. This mithraeum is, likely due to its rather secluded location, not the most well-presented Roman site. The course of the structure is still preserved and the three aisles are delineated with some modern columns. A course etching of the tauroctony is presented centrally. Nevertheless, it remains one of the more evocative, atmospheric ancient sites one is likely to encounter.

SPAIN

- Augusta Emerita, Mérida

Established by Emperor Augustus in 25 BC, Augusta Emerita became an encampment of military personnel (indeed, the name of the settlement refers to the veterans of Augustus). The camp grew rapidly into one of Rome’s key capitals of the region then known as Lusitania. Unlike many Roman towns, Augusta Emerita by all counts continued to prosper despite the influx of Visigoths. The city landscape began to change somewhat, however, when it fell under the control of Arab Musa bin Nusair in the eighth century. Modern Merida offers one of the most substantial collections of ancient Roman structures outside of the Italian peninsula. So vast are its holdings that UNESCO named it a World Heritage Site in 1993. Among the highlights are a Roman theater originally dedicated by Marcus Agrippa in the late first century BC that is one of the best-preserved examples of such architecture today. There is also a Roman circus as well as a bridge built over the Guadiana River during the reign of Emperor Augustus. Added to the visit can be views of two Roman aqueducts, a temple originally dedicated to Diana, an elaborate mithraeum house and several columbaria as part of the funerary district just outside the original city’s border.

Mithraeum House, Augusta Emerita. The house was given its name on account of its proximity to the ruins of a sanctuary dedicated to Mithras. Photo by Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Els Munts Mithraeum, Mitreo dels Munts

The Roman villa complex of Els Munts at Altafulla just east of Tarragona dates from the first century AD and is a sprawling site that incorporates a number of features. These include a temple, baths and a colonnade. The owner of the villa around the middle of the second century was a local administrator called Caius Valerius Avitus, who lived here with his wife Faustina.

The substantial ruins of the villa have been conserved and visitors may also visit a small museum detailing the history of the site. Points of interest include stretches of painted wall and well-preserved mosaic flooring.

Roman Villa del Munts – remains of the mithraeum. By Enric – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

- Fuente Álamo Mithraeum

The Roman villa at Fuente Álamo north of Puente Genil was the property of a wealthy landowner. He adorned his rural home with such lavish features as private baths and geometric and figurative mosaics. He even had a temple dedicated to Mithras erected in its grounds.

The villa and its temple are now preserved as an archaeological site, complete with a small museum. The mosaics, which include a depiction of the Three Graces and scenes from the life of Dionysius, are considered among the most important in Spain.

Archaeological site at the Fuente Álamo, Puente Genil, Spain. By Rafael Jiménez from Córdoba. CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Igabrum (Cabra) Mithraeum

“Known as Igabrum or Licabrum in Roman times, Cabra was a strongly fortified and prosperous town. There were temples dedicated to Fortuna and Apollo and, in addition, a Mithraeum. This is famous for a marble statue called the ‘Mithras Tauroktonos of Cabra’, the only example of a statue on this theme to have been found in Spain.

Virtually no trace remains of the Mithraeum today, but the statue is preserved in the Archaeology Museum in Cόrdoba.

Mithras of Cabra found in 1952 now in the Archaeological Museum of Córdoba. Photo by Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

ITALY

- Ostia House of Diana, Casa di Diana – Mithraeum

The House of Diana (Reg I, Ins III, 3-4) is a well-preserved four-storey apartment with shops and a Mithraeum. The building was likely used as the seat of a guild. It is named for a relief depicting Diana found in the courtyard. The building was first constructed during the Hadrianic period. A number of polychrome mosaics and brick stamps have been found dating to this earlier phase of construction. The entire building was rebuilt in yellow opus latericium around AD 130 to 150. This new construction roughly followed the original layout and was done at a slightly higher level so that the whole building was a step above ground level. On the south and west facades, a series of shops opened onto the streets, each with a mezzanine window. A decorative balcony ran above the shops overhanging the streets.

An elaborate water feature in the middle of the courtyard consists of a rectangular basin with a central raised fountain designed with semicircular and rectangular stepped niches around its perimeter. Water from the fountain cascaded down a series of shallow steps into the basin. Several large, well decorated rooms opened off the courtyard. The southern room originally had a plaster ceiling decorated with polychromatic geometric shapes, and wall paintings featuring Medusa heads, dolphins, and winged animals. This room was later converted into a stable with a basalt floor and fitted with a trough. At the same time, two rooms in the far north-east corner of the building were turned into a Mithraeum. These rooms would have been quite dark, with the altar lit by a skylight. The building remained in use until the 4th century.

Mithraeum on the House of Diana, Ostia. Photo from the www.ostia-antica.org website.

Although the upper levels have not survived, the House of Diana is known for its well-preserved multi-storey façade with windows and balcony overhang. The ground floor can be explored and its arrangement is clear. Visitors can see the fountain in the courtyard, as well as some wall decoration in the street-front shops.

- Ostia Baths of Mithras, Terme del Mitra

The Baths of Mithras (Reg I, Ins XVII, 2) was built in opus latericium during the Hadrianic period, and modified during the Severan period. The main entrance is from the east and leads onto an apodyterium (changing room). Bathers would then move into two large halls lined with decorative niches. To the south was the frigidarium (cold baths) which were decorated with a mosaic of Ulysses and the Sirens. Further south were two heated rooms without baths, one of which was a sudatorium (sweating room) with a basin in an apse. The southern-most bathing room was the caldarium (hot baths) with two pools. The service area further south contained a water-wheel that was operated by slaves to lift water to the various levels. The wheel had a diameter of over 7 metres, and delivered 1,000 litres of water each hour.

In the most northerly room of the bathing complex, an underground shrine of Mithras was found in the bath’s service areas. The shine was accessed via a narrow brick staircase whose entrance was between two walls that extended from a curved feature. The mithraeum was built as a long, low corridor with vaulted ceiling. Overall, it measured 15 metres long, 4.5 metres wide and only 2 metres high. Two small skylights are positioned so that sunlight would highlight a large marble statue of Mithras poised to kill a bull. An inscription in Greek records that is was made by the sculptor, Kriton the Athenian, during the 2nd century AD. Behind the statue, and concealed by a small cross-wall, was a door leading onto the service areas. The statue was found in pieces and discarded in the sewers, likely by the Christians who reused the baths in late antiquity.

The mithraeum of the Baths of Mithras in Ostia Antica. Picture by Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The structure of the baths are well preserved, and visitors can see the arrangement of the various rooms. Some decoration is still visible, including the mosaic of Ulysses and the Sirens, columns, and other architectural elements. Wear marks can be seen on the corridor walls where the water-wheel operated. The service tunnels and the dramatic underground mithraeum can also be explored. A plaster cast of the statue of Mithras and the bull has been placed in-situ.

- Vulci Mithraeum

It is uncertain when the Mithras temple was built, but the cult must have been strong in the city of Vulci since the temple, even if small, was decorated with rich statues of a type only wealthy people could afford. Although the temple is not exceptional in terms of its decoration or architectural design, it remains interesting for its function, while the statues found inside are of historical significance. Two of them are still located on the site, representing Mithras killing a bull. The temple is enclosed in the Vulci archaeological park and is open to visitors.

Mithraeum in Vulci. Photo by Mararie.

- Rome San Clemente Basilica and Mithraeum (Church of San Clemente al Laterano)

Dedicated to Pope Clement I, Bishop of Rome from AD 88 to 99 and one of the first Apostolic Fathers, this basilica actually presents 3 distinct layers of Roman history, with a complex history of use and reuse marking it out as a palimpsest of public and private, and pagan and Christian architecture.

The present basilica dates to medieval period, having been built in 1100 under the direction of Cardinal Anastasius. However, this structure –one of Rome’s most richly decorated basilicas (a surprise considering its rather reserved external appearance) – was built atop an earlier 4th century basilica. The motivations for rebuilding remain unclear. This first basilica is known to have been in use from at least the year AD 392 thanks to the writings of St Jerome.

The layers of history do not stop at the 4th century however. This early Christian basilica was built atop a conglomeration of much older buildings. These included some kind of industrial space, which may well have been the imperial mint (dating to the Flavian era), a hypothesis prompted by the representation of a similar building from the Severan Marble plan (a 3rd century map of the ancient city). There was also an insula, an apartment block here, adjacent to the mint. Further back through the archaeological levels, there are even traces of a much older place of residence here; the remains of a possibly Republican-era villa that some have speculated may have been destroyed by the Great Fire in AD 64.

Paganism was also discovered in the archaeological layers beneath this church. The site of a Mithraeum, a subterranean place of worship for followers of the eastern god Mithras, was discovered on the site of the former insula.

The Basilica of San Clemente al Laterano is without doubt one of the most fascinating, and often overlooked, archaeological experiences available in the ancient city. Visitors to the Basilica are able to explore not only a glorious example of early Christian art and architecture, but they can then descend through the layers of history to see what lies beneath. Within the present Basilica, alongside a host of spoliated ancient material put to use in new, decidedly Christian contexts, there are also exceptional examples of medieval artwork, including the 12th century mosaics in the apse and the exuberant Cosmatesque flooring. Christian artwork is also evident in the first subterranean layer, with the first basilica being the home of some of the best early medieval wall paintings to be seen in Rome.

Further still below ground, where it gets noticeably cooler and damper, one is able to explore the foundations of the earlier, ancient structures. The highlight of this subterranean tour however is certainly the Mithraeum. The highlight remains the speleum, or cave, the central worship space. Here an altar was excavated, featuring the iconic scene of Mithraic worship: the tauroctony, showing Mithras (identifiable with his peaked Phrygian cap) slaying the bull. There was also a bust of Sol, the god of the sun and the fragments of statues of Cautes and Cautopates (the torch bearers), two other prominent figures within Mithraic religion. All of these remains are still presented at the site today.

- The Mithras Temple under the Santa Prisca Basilica on the Aventine Hill – Rome

The monks of the neighbouring monastery dug under the church for years, hoping to find the old Christian meeting place. They were unsuccessful, but in 1934 a Mithra Temple or Mithraeum was discovered. This would only be excavated in the period 1953-1966. This was done under the supervision of two Dutch archaeologists, M.J. Vermaseren and C.C. van Essen. The Christian oratory from the end of the second century was also uncovered then.

As often happened, the Christians triumphantly built the apse of their new church right over a Mithras sanctuary. When they got hold of the mithraeum, they smashed the statues and chopped down the wall paintings with axes.

When, in the late 1950s, archaeologists carefully sieved the earth that had filled the Mithraeum, they found fragments of the stucco statues of Mithras and Serapis, which had been preserved underground for many centuries. The pieces were collected and pieced together and the damaged wall paintings restored.

Like other similar sanctuaries in Rome, this mithraeum is integrated into a house, the underground part of which extends under the northern part of the church and the surrounding courtyard. According to stamps and indications on the bricks, the original house was built in 95 BC and was rebuilt several times in the course of the second century AD.

There is discussion about the owner of the house. The theory that the house was occupied by senator Lucius Licinius Sura, a good friend of Emperor Trajan who became consul three times, is not shared by everyone. Some scholars state that this is the house in which Trajan lived before he became emperor.

In any case, at the end of the second century, the underground complex was expanded, no doubt to honour the Mithras cult, which was still very widespread at the time. The mithraeum certainly still existed in 202, which is shown by an inscription of a believer, who was ‘reborn’ on 21 November of that year through his initiation into the mysteries. A small museum has been set up here, the antiquarium. In addition to the objects from the Roman house, some fine statues are on display, such as a sun god and Serapis, originally an Egyptian deity that brought luck and healing to the people.

In this fairly well-preserved mithraeum we can distinguish a vestibule with a small room in the corner where the sacrificial animals were slaughtered, then the large triclinium, a room where the supplies for the service were kept, and finally the baptismal room.

In the niche at the entrance to the triclinium were statues of fertility and infertility, the torch-bearing twin brothers Cautes and Cautopates. The statue of Cautes has been preserved. Here too, there are rows of seats on both sides of the triclinium. In the niche on the back wall, we see a bull’s-eye of Mithras and Saturn. Saturn’s body is made up of amphorae covered in stucco. The walls of the triclinium are decorated with impressive frescos.

On the right, you see the ‘seven degrees of initiation’ depicted. To each degree of initiation corresponds a planet. Next to each degree of initiation is an inscription, starting with the Persian word ‘nama’ (honour); then follows the name of the degree of initiation, the word ‘tutela’ and the planet. For example ‘nana leonibus tutela Jovis’ which means ‘honour to the lions protected by Jupiter’. The degrees of initiation with the planets from low to high: corax (raven) – Luna (moon); nymphus (bridegroom) – Venus; miles (soldier) – Mars; leo (lion) -Jupiter; Perses (Pers) – Mercury; heliodromus (sun runner) – Sol (sun); pater (father) – Saturn.

In this mithraeum the planets belonging to Corax and Perses have been exchanged. Next to the degrees of initiation on the right wall, a procession of lions is depicted, continuing on the left wall. They carry a bull, a cock, a ram, a mixing barrel and a pig. At the end of the procession on the left wall, a cave with four persons is depicted. Mithras on the right and Sol on the left are served by two figures, one of whom wears a raven mask. This is the sealing of the covenant between Mithras and Sol. During the ritual meals, Mithras and Sol were represented by the priest and heliodromus. They were dressed alike and had the same attributes as Mithras and Sol.

A corridor leads to a crypt from the period between the seventh and ninth centuries. From here, a staircase leads to the ancient titulus located under the floor of the present church. Here you can see the remains of the ancient frescoes mentioned earlier.

The underground Mithraeum of the Santa Prisca is open to the public on a limited basis and only by reservation or appointment. It is open every second and fourth Saturday of the month for individuals at 4 pm and for groups at 3 pm and 5 pm.

Mithraeum of Santa Prisca. Picture from the website of the Soprintendenza di Roma.

- The Temple of Mithras under the Baths of Caracalla – Rome

The fossa sanguinis in the Mithras sanctuary under the Caracalla baths has now also been restored. Work on the actual temple has been intensive over the past ten years. This brings to an end an extensive restoration period of this magnificent underground complex.

This is the largest Mithras sanctuary ever discovered and it is possible that it was the largest the empire had ever known. The fossa sanguinis is the large hole in the floor through which the blood of the sacrificed holy bull flowed. The whole system, with the accompanying tunnels, has been reconstructed in recent years.

Very soon after the inauguration of Caracalla’s enormous thermal baths in 216, a considerable part of the underground space was reserved for the construction of a huge sanctuary for the cult of the god Mithras. Today, all debris, waste and excess stone have been removed from the so-called sacred hall (measuring over 25 x 15 m). Part of the mosaic floor is still visible, inlaid with black and white tiles. In the middle of the floor is a deep hole in the ground of more than 2.5 m. It is the original fossa sanguinis, the system in which the sacrificial blood was collected.

An ingenious drainage system connects the hole to various underground tunnels. At certain times, these provided light. All open tunnels and connecting pits were investigated. This led to the discovery of many new underground spaces from which Caracalla’s baths were kept running. This is an almost intact system of passages, ovens and fireplaces that provided hot water for the baths. Sanitary facilities from ancient times were also discovered. A fresco showing the god Mithras was also restored. It has an unusual blue colour, but also shows chisel marks, as if the face had been chiselled away, perhaps as a result of a damnatio memoriae from the Christians, who wanted to erase all memories of what they considered a pagan cult.

- The Mithraeum of Santa Maria Capua Vetere – Rome

The mithraeum of Santa Maria Capua Vetere dates back to the second century AD, and contains one of the best preserved frescoes of a tauroctony. It has been restored and is open to the public. All useful information on the website of Atlasobscura.

Mithraeum in Ancient Capua. By Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Featured image: Mithras relief in the Musée de La Cour d’Or of Metz. By TimeTravelRome. CC BY-SA 2.0.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Turcan, Robert, Mithra et le mithriacisme, Paris, 2000.

Ulansey, David, The Mithraic Lion-Headed Figure and the Platonic World-Soul.

Méndez, Israel Campos, In the Place of Mithras: Leadership in the Mithraic Mysteries.

Mastrocinque, Attilio, Des Mystères de Mithra Aux Mystères de Jesus.

Turcan, Robert, The Gods of Ancient Rome: Religion in everyday life from archaic to imperial.

Hutton, Ronald, The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles:Their Nature and Legacy.

Sauer, Eberhard, The end of paganism in the north-western provinces of the Roman Empire:the example of the Mithras cult.

Walters, Vivienne J., The cult of Mithras in the Roman provinces of Gaul, Brill

Bivar, A. D. H., The personalities of Mithra in archaeology and literature

Lane Fox, Robin, Pagans and Christians.

Mary Beard, John A. North, S. R. F. Price, Religions of Rome: A history.

Marleen Martens, Guy De Boe, Roman Mithraism, (2004).

Clauss M., Gordon R. The Roman Cult of Mithras; the God and his Mysteries, Routledge, 2001.