Those who travel to Venice do not necessarily have in mind that Venice is home to several masterpieces of ancient art. In particular, Venice has – and exhibits – the famous Grimani Collection, whose magnificent ancient sculptures are displayed in the Archaeological Museum of the city.

In 2019 a very special event took place: an exhibition called “Domus Grimani”. At this date, part of the Grimany collection joined for a short period the palace of its former owner – the recently restored Palazzio Grimani. For the first time in 400 years the ancient marbles could be seen again in their original setting, and they were exhibited according to the tastes of the time.

I visited this beautiful and unique exhibition – unfortunately finished for a while – and I have the pleasure to share below some photos and memories from my visit. But first, I would like to say a few words about the family of Grimani, their palace and their Collection, which gave birth to the first public museum in Venice.

Palazzo Grimani – Entrance to the Museum. Photo by Timetravelrome.

The Palace of Grimani

The Grimani Palace in Santa Maria Formosa was built in the Middle Ages at the confluence of the canals of San Severo and Santa Maria Formosa. The palace, originally constructed on a Venetian-Byzantine plan, was modified and enhanced during the fifteenth century, becoming residence of the doge Antonio Grimani – a skilled spice merchant and first doge of the family. Antonio donated the palace to his sons (Domenico, Girolano, Pietro, Vincenzo and Marino), but the palace decorations were achieved by song of his son Girolano, his nephews Giovanni (1506-1593), Patriarch of Aquileia, and his brother Vettore. Until 1865, the palace remained the property of the Grimani family. By our time, and after several changes of owners, the palace was in an advanced state of disrepair – in 1981 it was acquired by the city of Venice. After a long restoration, it opened to the public in 2008.

Photo of the Grimani Palace before restoration. Source: “The restoration of Palazzo Grimani di Santa Maria Formosa in Venice”, Loggia N27, 2014.

The centerpiece of the Grimani palace is the Tribuna – a room that once housed dozens of statues and busts, the most beautiful of the Grimani collection. The room is unique in Venice, as it was inspired by the ancient Roman domus mixing roman style with the cultural climate of the Renaissance. Embellished with ancient and precious marbles such as yellow alabaster, green serpentine and red porphyry – from the eastern Mediterranean where the doge Antonio Grimani made his fortune as a spice merchant and military – the space was conceived as a spectacular reception hall, where part of the family collection was exhibited.

Tribuna East – view during the “Domus Grimani” Exhibition. Photo by Timetravelrome.

Grimani Family and their Collection

The story of the Grimani collection began with the death of Domenico Grimani (1461 – 1523) – the Venetian Cardinal and son of the doge Antonio. Domenico has accumulated valuable antiquities during his life in Rome – his workers found many ancient statues while building his villa and working in his vineyards located on the Quirinal – there were vineyards in Rome at this time as the city had lost many inhabitants in the Middle Ages. Stricken by an illness in the Roman summer of 1523, Domenico Grimani composed his last will: at his death, a collection of Flemish paintings and some 20 classical sculptures in storage in Venice were to become property of the state.

Cardinal Domenico Grimani – After Lorenzo Lotto – UK Royal Collection. Public domain.

These paintings and antiquities had to be arranged in a room in the donor’s honor. This first collection remained in the Palazzo Ducale until 1586, when antiquities were entrusted to Giovanni Grimani, the Patriarch of Aquileia, pending the completion of the new public museum. A few months later, following the example of his illustrious uncle, Giovanni has decided to donate his own collection of 150 antiquities to the state. So, the collection was first started by Domenico Grimani and was subsequently extended by one of his four nephews – Giovanni.

Giovanni Grimani was the youngest among four brothers and he lived the longest live – he has inherited or purchased the assets of his brothers, including the collection of his brother Cardinal Marino. By 1586, when Giovanni Grimani took over the collection of his uncle Domenico, the octogenarian Patriarch of Aquileia was the most knowledgeable collector and connoisseur of antiquities in Venice. Disappointed in middle life in a bid to follow his uncle and brothers Marino and Marco to a cardinal’s honours in Rome, he had contented himself with the patriarchate and retiring to the family palace at Santa Maria Formosa – transforming it into a vast and famous museum of art.

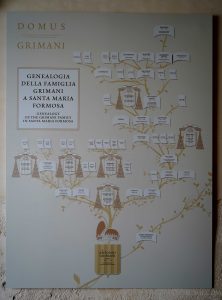

Family tree of the Grimani. Photo by Timetravelrome.

Giovanni Grimani had no direct heirs and he was concerned that his collection would be dispersed after his death. So, in February 1587, he announced that he wished to offer his collection of antique sculpture to the Republic, provided it could be displayed in a “permanent setting”. Giovanni died in October 1593 but the chosen “permanent setting” for his collection at the Biblioteca Marciana was still no ready. The death of Giovanni forced the Signoria of Venice to accelerate the works on the “Statuario Publico” – they were overseen by the Procuratore di San Marco, Federico Contarini, who added to the Grimani collection some 17 sculptures he owned himself. At last, in the summer of 1596 the Statuario Publico at the Biblioteca Marciana was completed. This collection comprising antiquities from collections of Domenico Grimani, Giovanni Grimani and Federico Contarini became the nucleus of the National Archaeological Museum of Venice, where it is still on display until now.

Anton Maria Zanetti il Giovane, Statuario Pubblico della Serenissima, parete d’ingresso, Venezia, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana. Source: “Immagine originaria e stratificazione di identità mutate“.

Many pieces of the initial collection – busts of Apollo and Caracalla, head of Aphrodite and Dionysus – have been exhibited at the Biblioteca Marciana for 400 years, until the library’s had to undergo a restoration: in 2019 they were moved to the Palazzo Grimani for a temporary exhibition – the “Domus Grimani”.

‘Domus Grimani’ exhibition

The Tribuna, an actual “chamber of antiquities”, is the inner sanctum where Giovanni Grimani received his most illustrious guests. Illuminated from above and inspired by the Pantheon, it constitutes the pivot and the final destination of the itinerary along the rooms that precede it. It was originally accessible through a single doorway, but some small modifications have been made over the centuries—such as the installation of a large window and a second doorway leading to the Neoclassical room, which was used as a bedroom in the late eighteenth century. Visitors to the Domus Grimani exhibition have seen the Tribuna as it was in Giovanni’s day, thanks to the installation of two temporary architectural niches.

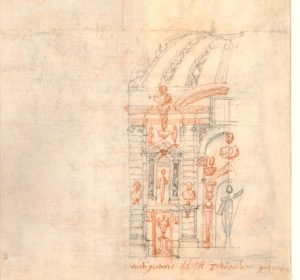

Verso of a drawing by Federico Zuccaro, circa 1582: study after part of the Tribuna of the Palazzo Grimani adorned with antique sculpture. Source: British Museum.

Tribuna South – during the “Domus Grimani” Exhibition. Photo by Timetravelrome.

Tribuna South and West – during the “Domus Grimani” Exhibition. Photo by Timetravelrome.

Exhibition highlights

At the center of the Tribuna one could see the “Rapt of Ganymede”, a roman copy made after a Greek Hellenistic original. In mythology, Zeus wanted to kidnap Ganymede and take him to Mount Olympus, where he would be the ‘cup holder to the gods’. Zeus disguised himself as an eagle, sweeping down from the heavens to carry Ganymede away. According to a legend, this sculpture would be a gift from Suleiman the Magnificent…

Rapt of Ganymede under the ceiling of the Tribuna. Photo by Timetravelrome.

Rapt of Ganymede – close up. Photo by Timetravelrome.

Another highlight of the Exhibiton was Aphrodite, AD 150-200: the sculpture was strongly restored in the Renaissance by Tiziano Aspetti. A hand of Aphrodite was added, as well as its head and the cupid besides…

Statue of Aphrodite or Capitoline Venus AD 2nd c. Head and bust restored by Tiziano Aspetti. Photo by Timetravelrome.

The next bust is probably the most enigmatic one: According to some attributions, it is a portrait of Antinous as a priest of Isis from Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli. As other busts of Isis priests, there is a cross-shaped mark on the skull of this portrait, but it is hard to say – despite some resemblance – whether the artist has indeed represented Antinous.

Antinous (?) as a priest of Isis. Photo by Timetravelrome.

My personal favorites of the exhibition include some anonymous portraits, such as this male bust dated to the 3rd century AD and a woman marble portrait, dated to the first half of the 3rd century AD.

Portrait of a man 3rd century AD with a Renaissance bust from Luni marble. Photo by Timetravelrome.

Portrait of a woman 205 – 235 AD bust and neck added during Renaissance. Photo by Timetravelrome.

Imperial portraits were represented by a portrait of Caracalla, a 16-century portrait of Hadrian, a marble bust of Aelius (?) and this well preserved bust of Commodus.

Bust of Commodus as a youth 175-177 AD. Photo by Timetravelrome.

Two masks of Pan were part of the Tribuna decorations.

Mask of Pan – middle of the 2nd c AD. Photo by Timetravelrome.

But the main focus attention at the Exhibition was obviously the Tribuna itself: restored to its original beauty, the Tribuna offered a rare glimpse into the artistic taste of the Renaissance collectors of antiquities. Unfortunately, after the end of this temporary Exhibition in May 2021, the Tribuna returned to its beautifully restored but still less spectacular state.

Tribuna North. – during the “Domus Grimani” Exhibition. Photo by Timetravelrome.

Sources:

https://www.venetianheritage.org/project

Cardinal Domenico Grimani’s Legacy of Ancient Art to Venice, Marilyn Perry, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 41 (1978), pp. 215-244

The Statuario Publico of the Venetian Republic, Marilyn Perry, Saggi e Memorie di storia dell’arte, Vol. 8 (1972), pp. 75-150, 221-253

The restoration of Palazzo Grimani di Santa Maria Formosa in Venice, Loggia N27, 2014.

Immagine originaria e stratificazione di identità mutate“. Massimiliano Ciammaichella and Gabriella Liva. 2° Convegno Internazionale dei Docenti delle Discipline della Rappresentazione Congresso della Unione Italiana per il Disegno.