Author: Kieren Johns.

The Romans first made direct contact with Britain in the middle of the 1st century BC, when Julius Caesar invaded in 55 and 54 BC. Rome’s most famous general believed that the island’s native Celtic people had been providing support to the Gauls in France, against whom he was waging the war that would secure his fame. Within a century, Britain itself would go from being shrouded in mystery to invaded by the Roman armies and incorporated into the Empire.

The century between Julius Caesar’s first invasion and the Emperor Claudius’ decisive imperial invasion in 43 BC, much of the Roman world had undergone tremendous change. The Republic was dead, ended by a period of protracted civil wars and the vast territories of Empire, from northern Europe to the edges of Asia Minor, were now ruled by a single emperor. Nevertheless, aspects of Roman society and culture endured and evolved, untroubled by these blood-soaked political turbulences.

The general appearance of Roman civilisation, how the empire looked to the people that called it home, was remarkably similar across its enormous expanse. The Roman villa, the opulent country adobe, was to be found right across the Roman territories. Even in Britain, on the very edges of the Empire, the countryside was dotted with these icons of Roman civilisation.

Here are 7 of the best Roman villas that you can still explore in Britain today:

1/ Chedworth Roman Villa – Home of the Nymphs

Found in the county of Gloucestershire in western England, the Roman villa at Chedworth is actually one of the largest ever discovered in the country. Believed to have been built in around about 120 AD, as the Roman Empire was entering its Golden Age under the auspices of the Five Good Antonine Emperors, archaeological work shows that the villa was built up in stages. The occupants of the villa, as well as being wealthy, would likely have been well connected with Roman Britain: the villa is situated just a little way from the main Roman road in Britain, the Fosse Way, whilst it is close to both the city of Corinum Dobunnorum (modern Cirencester) and the town of Glevum (Gloucester).

Chedworth Roman Villa -View from northeast. By Pasicles – Own work, CC0.

The villa reached its peak in the 4th century AD, at which time it appears to have fully embraced the trappings of an aristocratic residence. As well as the already large bathing complex (built in the 3rd century), during this time a significant portion of the northern wing was converted to become an additional bathing suite (including laconicum, or dry heat baths), whilst the triclinium (dining room) was at this point ornamented with the fantastic mosaic decoration that one can still see today despite the villa falling into ruin in the 5th century.

Any villa that has two bathing complexes clearly has exceptional water access, and Chedworth was actually built on the site of a natural spring. This appears to have become a central feature of the site, and a Nymphaeum – a pool and fountain complex – was built in the northwest of the villa. This was originally dedicate to the water-nymphs who dwelt in the spring waters, but over time its function appears to have changed as a Christian chi-rho symbol was discovered scratched into the rock here.

Today, visitors can explore the remains of the nymphaeum and villa, which are well maintained and presented. The mosaics in particular are well worth exploring, and information about the villa is presented in the excellent Visitor Centre on site. You can further explore Roman Chedworth too – less than 1km from the villa the foundations of a large Romano-British temple have been uncovered. Some of the smaller finds contained at the Villa’s museum come from this site, including a stone carving of a hunting deity accompanied by their dog and stag.

Link to some official information: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/chedworth-roman-villa

2/ Great Witcombe Roman Villa – Home is where the Bath is

Also located in Gloucestershire in the west of England, Great Witcombe villa is believed to date to the 1st century AD, making it slightly earlier than its Chedworth counterpart. It too, however, appears to have been destroyed or abandoned in the 5th century. This is where the similarities end however, as Great Witcombe Villa is markedly different to other contemporary structures. For one it was built over four terraces to offset the challenges presented by the awkward terrain. This may have impacted the layout of the villa too, which is highly irregular for a residential building.

Roman Villa, Great Witcombe. By Robert Powell, CC BY-SA 3.0.

The villa is recorded as being in excellent condition upon its first excavation in the 19th century. However, modern visitors have been somewhat let down by the poor conservation practices of the Victorians, which means that the heavy English rains have washed away many of the plastered walls that were originally still standing. Nevertheless, the low walls and foundations that are still standing give a good impression of the shape and size of the complex, whilst certain features in particular remain very interesting. For one, the villa was – like Chedworth again – well serviced by water. The remains of both the bath house and parts of its marine-life mosaic decoration, and the latrine are excellent here, with the hypocaust heating system notable for its state of preservation. A small room with niched walls is believed to have fulfilled a religious role, perhaps as a shrine. Also of note is the Octagonal room, an unusual feature dating to the 4th century AD.

3/ Littlecote Roman Villa – A home for Orpheus

Found in the village of Ramsbury in the southern county of Wiltshire, the Littlecote Roman Villa appears to have been a site of profound change over the course of the Roman occupation of Britain. The settlement likely began as a small, temporary military encampment, located to guard the River Kennet. Over the years of occupation however, and the gradual decrease in need for military presence (in the south of Britain at least), it developed into a more peaceful site, with evidence of food manufacturing found here, including baking ovens and grinding stones from around 70 AD to 120 AD.

Littlecote Roman Villa, the Orpheus mosaic. By Przemysław JahrAutorem. Public Domain.

Over the course of the 2nd century however, this small site developed again, becoming a large two-story villa, with the typical wings and bathing suite. For some reason that is not clear, a major rebuilding was required in the late 3rd century – perhaps in relation to the chaos that afflicted the western empire more generally at this time. Regardless, the mosaics that can still be seen in the villa remain some of the best to be seen in Britain; colourful, ornate, and rich in narrative details.

Numismatic evidence from the site indicates that in the mid-4th century underwent its most profound change; agricultural production appears to have ceased, with the site acquiring a religious function. One of the original barns from the agricultural villa was converted into a courtyard whilst an exceptionally early triconch hall – a space for religious worship – was built next to the bathing complex and ornamented with the villa’s famous Orpheus mosaic. Interpretation of the mosaic remains contested – and frequently includes not only Orpheus, but figures such as Bacchus and Apollo. This would place the mosaic seemingly out of time in a rapidly Christianising empire, leading some to suggest that the mosaic belongs to the era of Julian the Apostate, the notorious last pagan emperor, who attempted to motivate a pagan revival (361-363 AD).

4/ Brading Roman Villa – Home of the Cockerel Conundrum

Off the southern coast of Britain is the Isle of Wight, and here one can explore the site of Brading Roman Villa with its excellent modern museum and visitor centre. Although not as big as other villas on this list, the example at brading displays many of the typical features of Roman villa architecture, including the central courtyard.

Brading Roman Villa. By Nilfanion – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

The Isle of Wight was brought under Roman control by the future-emperor Vespasian in the years of the Claudian invasion (ca.44 AD), and the first phase of the villa dates to around this time. This would suggest that Roman cultural values and styles found a ready audience amongst the natives. Over the coming century, the villa would be developed substantially into an impressive and opulent example of Roman residential culture transported to the edges of the Empire. Despite a devastating fire in the 3rd century – possibly linked to raids during the 3rd century crisis – Brading remained occupied well into the latest periods of Roman control in Britain. For instance, coins have been found that indicate that it was occupied until at least the reign of the Emperor Honorious in 395 AD.

Although it collapsed in the 5th century AD, the remains of the villa are still in reasonably good condition and are today expertly maintained undercover at the on-site Exhibition and Visitor Centre. The overall size and layout of the villa remains readily identifiable, whilst the real attraction of the site is undoubtedly the exquisite mosaic decorations. These include subjects as diverse as Orpheus, Bacchus, gladiators, and the mystery of the cockerel-headed man. Quite who this chicken headed figure is meant to represent remains contested with theories as diverse as the gnostic deity Abraxas, a gladiator called Gallus, or even the Emperor Constantius Gallus! Away from all of these, of course, it could just be nonsense, but this would somewhat detract from the richness of the other decoration.

5/ Fishbourne Roman Palace – A Home fit for a King?

We’ve covered Fishbourne Palace here at TimeTravel Rome before: it really is one of the best Roman sites that can be explored in Britain today. This palatial complex can be found in Chichester, West Sussex, on Britain’s south coast. Dating to around 75 AD, Fishbourne Villa is the largest residential building from the Roman era to have ever been uncovered in the UK, and indeed, it is the largest ever found north of the Alps – whoever lived here was seriously rich!

The garden at Fishbourne Roman Palace in Sussex. By mattbuck – Own work by mattbuck., CC BY-SA 4.0.

When it was originally excavated, it was suggested that this was once the home of the pre-Roman chieftain Tiberius Claudius Cogidubnus. King Cogidubnus would likely have been allowed to remain in his esteemed position in the south of Britain by becoming a client-king for the Romans. Although recent archaeological debates have focused on whether the villa actually belonged to Sallustius Lucullus – a governor in the late 1st century AD who would be murdered by Domitian – this sprawling residence is certainly fit for king.

The famous Cupid mosaic at Fishbourne Roman Palace in Sussex. By mattbuck – Own work by mattbuck., CC BY-SA 4.0.

The design and decoration, which features some exquisite and well-preserved mosaics, indicate just how quickly a recognisably Roman residential culture was adopted and expanded in Britain. Indeed, in both scale and shape, the villa at Fishbourne actually closely resembles contemporary imperial palaces in Rome, including the Domus Aurea of Nero, and the Domus Flavia of Domitian. Britain was clearly not the provincial backwater that some would have you believe!

Link to official information: http://sussexpast.co.uk/properties-to-discover/fishbourne-roman-palace

6/ Bignor Roman Villa – Gladiators and Gorgons

Just to the north east of Chichester (called Noviomagus Reginorum by the Romans) in West Sussex, one can explore some of the UK’s most excellently preserved and intricate ancient mosaic decoration at Bignor Roman Villa. Although smaller than the nearby Fishbourne Villa, the typical courtyard villa at Bignor is still well worth discovering.This villa appears to be quite a bit older than its neighbour at Fishbourne. Whilst the larger villa dates to the second half of the 1st century AD, the earliest structural finds from Bignor date to the last decade of the 2nd century (ca. 190 AD). At this point in time, the structure was a simple timber farm dwelling. It wasn’t until the mid-3rd century that the site appears to have undergone development, with the construction of a larger stone building. This more permanent structure was developed over the course of the century, with the additions of new rooms, a portico, and a hypocaust system to provide heating to the structure.

Bignor Roman Villa. By Poliphilo – Own work, CC0.

Bignor however is best associated with its mosaic ornamentation, and these date to the last phase of construction detectable at the site, in the first half of the 4th century (300-350 AD), by which point the villa is believed to have had some 65 rooms. The mosaics are located in these most recent structures which comprised an expansion of the northern wing of the villa. The subjects of the mosaics vary, acting almost as a who’s who of the ancient imagination with gladiators and gorgons amongst the characters depicted. There is also a simple geometric patterned mosaic in the northern corridor – featuring a Greek-key pattern – that measures 79ft, making it the longest mosaic in Britain. One thing that can be said with certainty is that whoever commissioned these scenes for their home was clearly considerable wealthy!

Mosaics at Bignor Roman Villa in Sussex. By mattbuck – Own work by mattbuck., CC BY-SA 4.0.

Link to the official website: https://www.bignorromanvilla.co.uk

7/ Lullingstone Roman Villa – Home of an Emperor?

Found near the village of Eynsford in Kent, in Eastern Britain, Lullingstone Roman Villa dates to the last decades of the 1st century AD (between 80 and 90 AD). The original occupants of the villa are unknown, but the size and wealth of the material recovered would suggest that they were either rich Romans, amongst the first to arrive from the Empire, or perhaps native Britons who keenly adopted Roman cultural practices. It appears to have been sited to enjoy the benefits offered by Watling Street, which connected Verulamium (modern St Albans) with Viroconium (modern Wroxeter, and one of the must-see Roman sites in Britain).

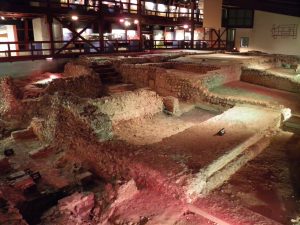

Lullingstone Roman Villa. By Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Some time in the mid-2nd century, the villa at Lullingstone was expanded significantly. A heated bath block, fuelled by a hypocaust system, was added. Two marble busts have been recovered from this period. It has been suggested that these depicted the residents of the villa, which may actually have served as the country retreat of the provincial governors who managed the imperial province on behalf of the emperor. Most intriguingly, there is evidence to suggest that these busts actually depict Publius Helvius Pertinax, who was governor of Britain in 185-86 and his father. These busts would connect the villa of Lullingstone, in the far corners of the Empire, with the very heart of Rome’s imperial history; by 193 AD, Pertinax himself was to become emperor, replaced the depraved Commodus, who was assassinated by his Praetorians. These busts are now kept in the British Museum, and serve to remind of how Emperors could be found at even the furthest edges of the Empire.

Sometime in the 3rd century, the villa was again expanded, so that the grounds now included an expanded bath house, a granary, and a structure that has been identified as a temple-mausoleum. The temple-mausoleum is one aspect of a colourful spiritual history for this villa. One room in the complex was used as a pagan shrine – dedicated to, and decorated by, local water deities. However, come the 4th century, the room above the original pagan shrine was converted into a space for Christian worship. The decorations in this room, including fresco paintings that depict a row of worshippers and a typical Christian chi-rho symbol. Although some of these are now displayed in the British Museum, they nevertheless represent that only known examples of Christian painting from Roman-era Britain. Visitors to the villa and the British Museum cannot help but be reminded of the complex spiritual landscape that was the reality of life in the Roman Empire.

Header picture source: Chedworth Roman Villa, museum and custodian’s house. By Tony Grist – Photographer’s own files, Public Domain.

————————

If you want to learn more about these beautiful villas and nearly 5000 other ancient roman sites and monuments, try our Timetravelrome app: