The city of Halicarnassus was almost extinct by the Roman Era, but it had been an extremely influential city in the shaping of the ancient world. As well as being the hometown of the famous historian Herodotus, it was also the site of one of the ancient wonders of the world and the seat of some impressive female rulers of Caria. Dorian settlers founded Halicarnassus, likely originating from either Troezen or Argos. Although women were not first in line for the throne, Caria was among the few ancient kingdoms that included them in the line of succession. At least three cunning queens of Halicarnassus were well-known and recorded in the history books.

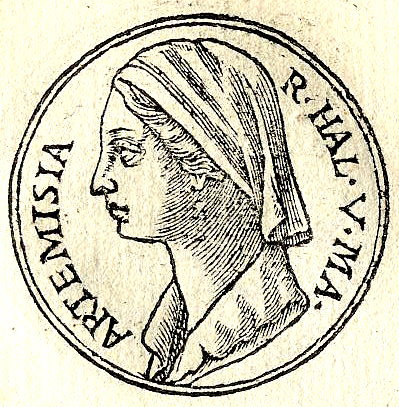

Artemisia I

Artemisia was the daughter of Lygdamis I, satrap of Halicarnassus under the Persians. She had taken the throne upon the death of her husband. Their son was still too young to hold power. In 480 B.C., she joined Xerxes’ invasion, not through coercion, but simply from a desire for valor and honor. Her five ships were among the best in his fleet. When faced with the defending Greek fleet, Xerxes sent round to all of his commanders, asking for their advice. All suggested that he fight, with the exception of Artemisia. She bravely suggested that he be cautious against the skilled Athenian navy.

Unfortunately for Xerxes, he did not listen to her. Although he did not disrespect her or her opinion, he was overly confident in the invincibility of his army. Some feared and others hoped that Xerxes would punish Artemisia, possibly with her life, for daring to speak out. However, he was actually pleased with her honesty and praised her boldness, despite following the advice of the others. The battle began in the straits of Salamis, and the Persians soon began to struggle. In the midst of the fighting, Artemisia was the only one to recognize the body of King Xerxes’ brother, Ariabignes, in the water. She was able to retrieve it from among the bloody debris, later returning it honorably to Xerxes.

Escape from Salamis

In the thick of the battle aboard her flagship, Artemisia realized that defeat was inevitable. She tried to sail out of the narrow passage, but an Athenian ship hotly pursued her, and the line of still incoming Persian ships blocked her escape. In a daring move, she rammed her ship into one of her own allies, sinking the friendly vessel. The Athenian ship subsequently believed she was either a Greek, or a defector, and it broke off the chase. She was able to extricate herself from the pandemonium. Had the Athenian captain known that the ship belonged to Artemisia, he would not have abandoned his attack. Athens had offered a bounty of 10,000 drachmas to any who could capture Artemisia alive.

Die Seeschlacht bei Salamis, 1868, by Wilhelm von Kaulbach, picture in public domain.

From their vantage point on the cliffs overlooking the sea, Xerxes and his advisers could make out Artemisia’s ensign aboard her ship, but could not see which ship she had rammed and sunk. Assuming it to be an enemy trireme, one of Xerxes’ court pointed it out, saying, “See, master, how well Artemisia fights, and how she has just sunk a ship of the enemy?” Also unable to see that she had sunk one of their own, Xerxes praised her and remarked, “My men have behaved like women, my women like men!” After the battle, Xerxes again sought advice. This time he listened to Artemisia, and withdrew the majority of his forces back to Persia.

Artemisia II

In 353 B.C., Mausolus, King of Caria, died after a twenty-four year reign. His widow, and sister, Artemisia II, took over as queen. She was distraught at the loss of her brother and husband, and commissioned the construction of a massive tomb for him. This grave, known now as the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, is one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. The word “mausoleum” in modern English is derived from King Mausolus and the splendid crypt that his wife designed. Artemisia also, apparently, drank a small amount of his ashes, mixed into a drink, each day after his death.

The rulers of the city of Rhodes highly disapproved of a woman ruler in Halicarnassus. They sent a fleet to attack her. Artemisia concealed her ships and soldiers in a secret harbor built by her husband. When the Rhodians arrived, she invited them to enter the main harbor and come up into the city. She and her infantry then massacred them. Meanwhile, her ships came out and captured the empty Rhodian vessels. She filled them with her own men, and sent them back to Rhodes. The Rhodians welcomed their ships home, utterly surprised when the Carian men disembarked and took control of Rhodes.

Another strategic deception allowed Artemisia to take the city of Latmus. She concealed her soldiers near the city. She herself led a large group of women, eunuchs, and musicians in a noisy procession out to sacrifice at the grove of the Mother of the Gods. The citizens of Latmus came out to watch the glorious procession, and the soldiers slipped in and took the city with ease.

Ada of Caria

Artemisia II’s sister was Ada, who was also married to another of their brothers, Idrieus. After Artemisia II died in 351 B.C., wasting away out of grief according to the ancient histories, Idrieus became king of Caria. He ruled from Halicarnassus until his death only seven years later. Ada succeeded him, but was usurped in 340 B.C. by their youngest brother, Pixodarus. She fled to the fortress Alinda, and was still taking refuge there when Alexander the Great invaded the region. Ada went out to meet him and surrendered Alinda to him freely, seeking an alliance through familial ties. She said she was too old to be his wife, but would gladly take a role as his mother.

Alexander kindly accepted, and after successfully taking the city of Halicarnassus in a great siege, he presented the city to Ada and returned to her control of the kingdom of Caria. Plutarch tells that they remained in contact throughout his ongoing campaigns, always on terms of greatest affection. Alexander always referred to her as “mother,” and Ada used to send Alexander pastries and sweetmeats, made by her best bakers.

Purported skeleton of Ada, Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology

Purported skeleton of Ada, Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology, photo by

Livius.org licensed under CC0

What to See Here:

Unfortunately, modern Bodrum has largely covered the remains of ancient Halicarnassus. However, one is able to trace almost the entirety of the ancient defensive perimeter. Similarly, the location of several temples and the city’s theatre are identifiable, even if little material remains standing. For an account of the ancient city, there are few better sources than the description provided by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius.

Although was an earthquake destroyed the great Mausoleum in the Middle Ages, enough has been recovered to allow historians to piece together a reasonable understanding of what the structure may once have looked. Remains of the Mausoleum’s statuary decoration are displayed in the British Museum.

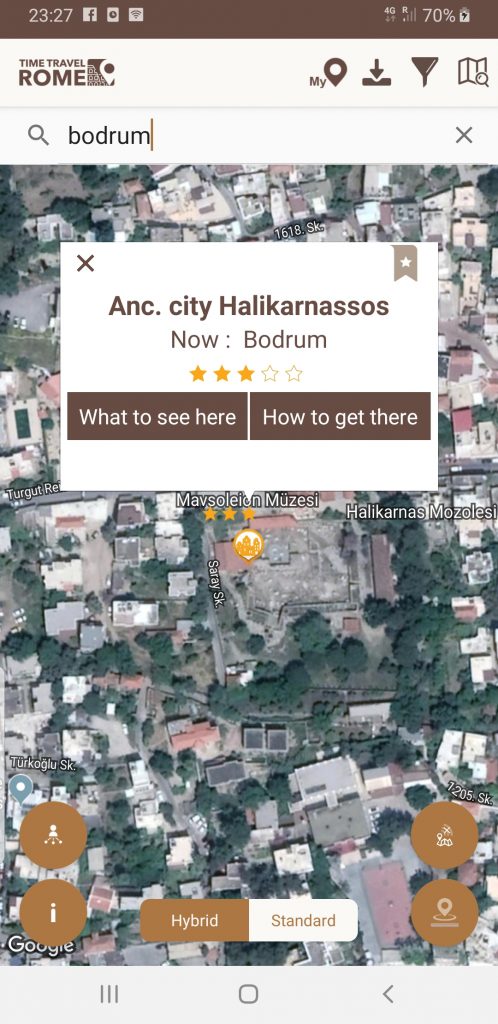

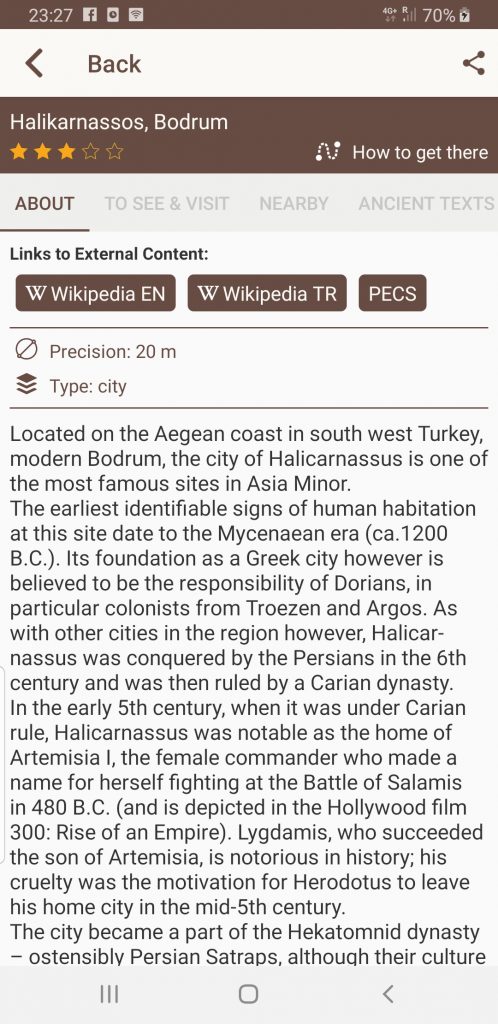

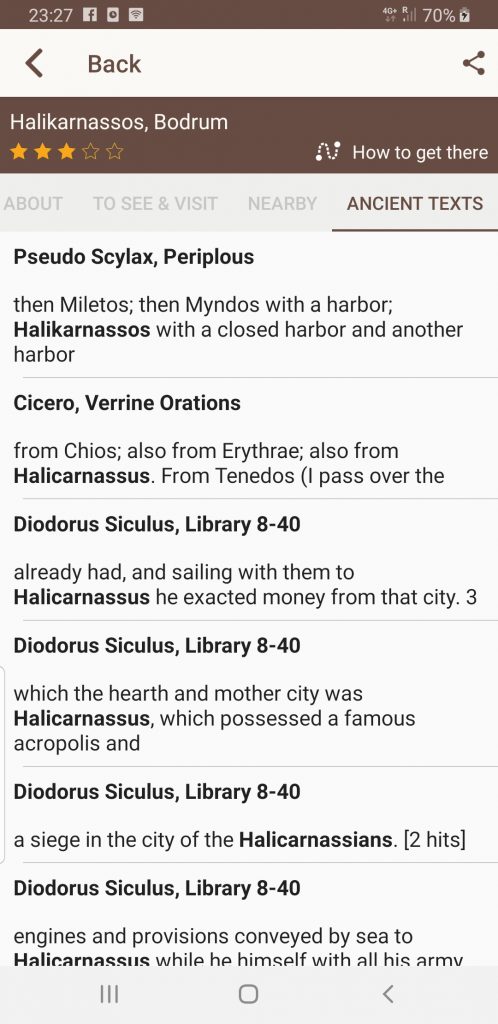

Halicarnassus on Timetravelrome app:

To find out more: Timetravelrome.

Author: written for Timetravelrome by Marian Vermeulen.

Sources: Herodotus, Histories; Plutarch, Life of Alexander; Polyaenus, Stratagems; Arrian, Anabasis; Justinus, Epitome of the Philippic History.

Header photo: The theatre of ancient Halicarnassus, by Carole Raddato licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0