For the first time, the underground tunnels beneath Rome’s extraordinary Baths of Caracalla are open to the public. Following the completion of renovations that began in 2015 and cost €350,000, the secret underground galleries of the baths have been revealed. From June 18 to September 29, 2019, visitors can immerse themselves in a special visual and musical exhibition within the subterranean tunnels. After this date, the subterranean levels will remain accessible, with a new pedestrian route planned to connect the Baths of Caracalla with the Colosseum, the Circus Maximus, and Trajan’s Markets.

Caracalla Baths, photo by Michelle Richards, used by permission of the author

Spectacular Building

The massive bath complex was constructed by the Emperor Caracalla, of the Severan dynasty, between AD 212 and 216. The Baths of Caracalla were the second largest bathing complex in the Roman Empire (only the Baths of Diocletian were larger). The large natatio (a swimming pool the size of a modern Olympic pool) was roofless, and surrounded by overhead bronze mirrors positioned to direct sunlight into the bathing area. The massive columns of the central frigidarium were 12 metres high and weighed almost 100 tonnes. In addition to the series of hot and cold bathing rooms, the baths boasted a sauna, an enormous public library, two palaestrae, an athletic track, gardens, massage rooms, perfumeries, cafes, and shops. Excavations of the underground levels also found a Mithraeum and water mill.

Thirteen thousand prisoners of war from Septimius Severus’s earlier Scottish campaign laboured to construct the baths. Six thousand skilled tradesman and six hundred designated marble workers were also employed. The massive construction project would have required the delivery of 2,000 tonnes of material every day over the six years, in addition to the intricate decorative work, in order to complete it within that time. The Aqua Marcia aqueduct was built by Caracalla at the same time specifically to serve the baths.

The aqueduct supplied a massive 70 litres (18.5 gallons) of water every second to the baths. Water was stored in an enormous cistern divided into 18 compartments with a total capacity of 80,000 cubic metres. Fires were kept burning day and night to heat the water that provided steaming baths for Rome’s citizens. An entire subterranean level complete with storage rooms, wide passageways, and 50 furnace ovens, exists beneath the baths. It is this technological heart of the baths that is now accessible to the public.

Hot Water for 6.000 Daily Visitors

During its peak, some 6,000 Romans visited the baths every day. The baths were large enough to accommodate 1,600 bathers at any one time. To keep the water in the caldarium’s seven hot pools at a constant, sweltering 40°C (104°F), slaves tended the 50 underground ovens 24 hours a day. It required 10 tonnes of wood to be carted into the city every day just to heat the water for the Baths of Caracalla. A 3km (almost 2 mile) network of tunnels connected the 50 ovens. The tunnels were 6 meters (20 ft) wide, with vaulted ceilings, and brick floors. Wheel ruts in the brickwork show the passage of centuries of carts, laden with wood.

The ovens were built as brick platforms mounted on steps with storage space beneath for the wood. The water was heated in massive copper tanks and fed through the baths in a network of lead pipes before draining away. For the slaves working in these subterranean levels, it would be been stiflingly hot. To recreate the experience, light and sound installations animate the underground galleries with fire and water as visitors walk through the underground passageways. Within the tunnels, it is now possible to see, fully restored, one of the massive ovens that once heated the water that flowed through the complex.

Palaestra in the Caracalla Baths, photo by Michelle Richards, used by permission of the author

What to See Here:

The Baths of Caracalla are one of the most majestic archaeological sites in Rome. Its incredible preservation clearly shows the architectural and technological greatness of the ancient Romans. Even though only an incomplete shell of its brick-faced concrete structure survives, this is still enough to give you a unique sense of the scale of Roman monumental architecture; something that’s easily lost in the city, even in sites like the Forum.

Changing Room in the Caracalla Baths, photo by Michelle Richards, used by permission of the author

What the baths don’t give a sense of is the elaborate decorations that would have ornamented its floors, walls, and ceilings. Only traces survive: of naval scenes (reminiscent of those found at Ostia) and, more famously, the large curved floor mosaic that shows all of the famous gladiators and athletes of the time—people once as recognisable as any of today’s A-listers.

Not to miss is the bath complex’s triple groin vaulted frigidarium. As the most important room in the baths, it would have been breathtaking: supported by grey granite columns and white marble capitals. This is to say nothing of its sculptural display, of which, regrettably, nothing remains onsite. Offsite, however, in the Archaeological Museum of Naples, is the famous statue of the Farnese Hercules taken from the baths: a sculptural addition no small part influenced by the fact that Hercules was a god Caracalla tried to cultivate an affiliation with.

You may feel the grandeur of the edifice watching a short 3D video.

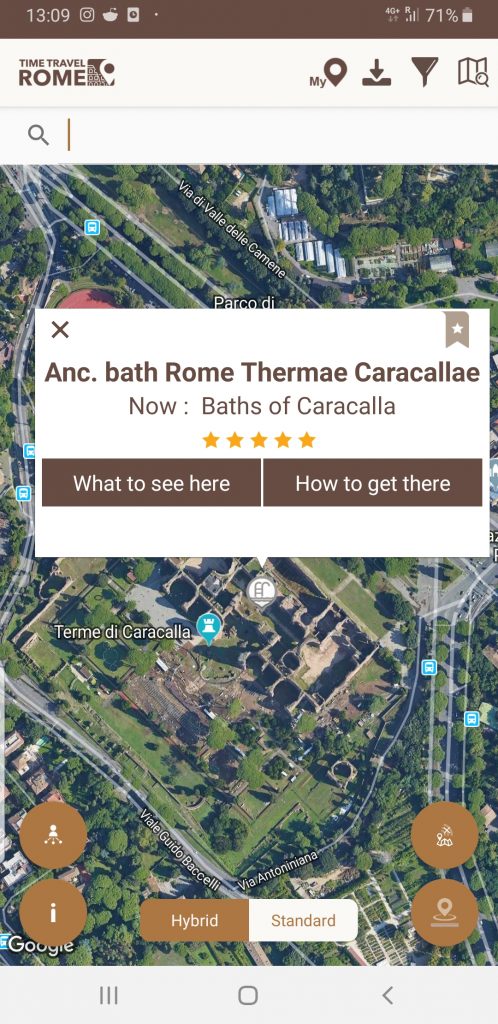

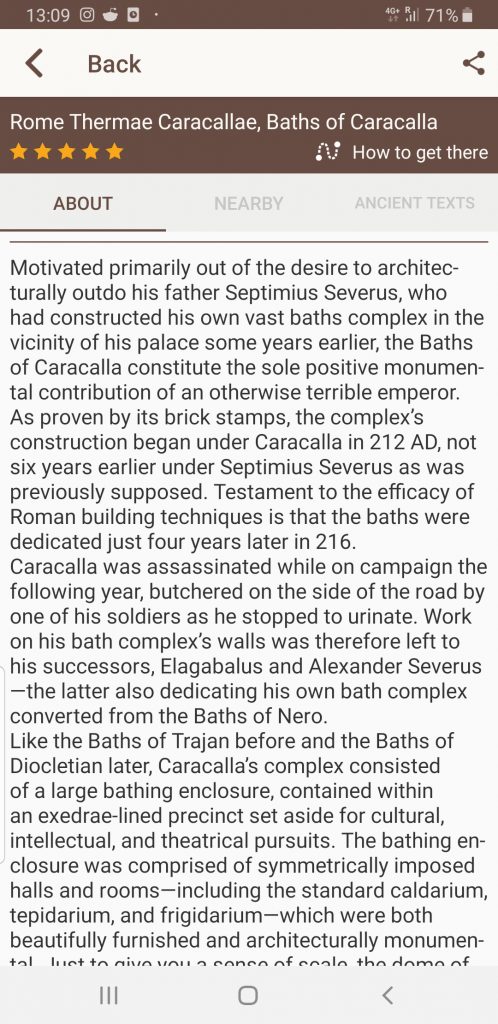

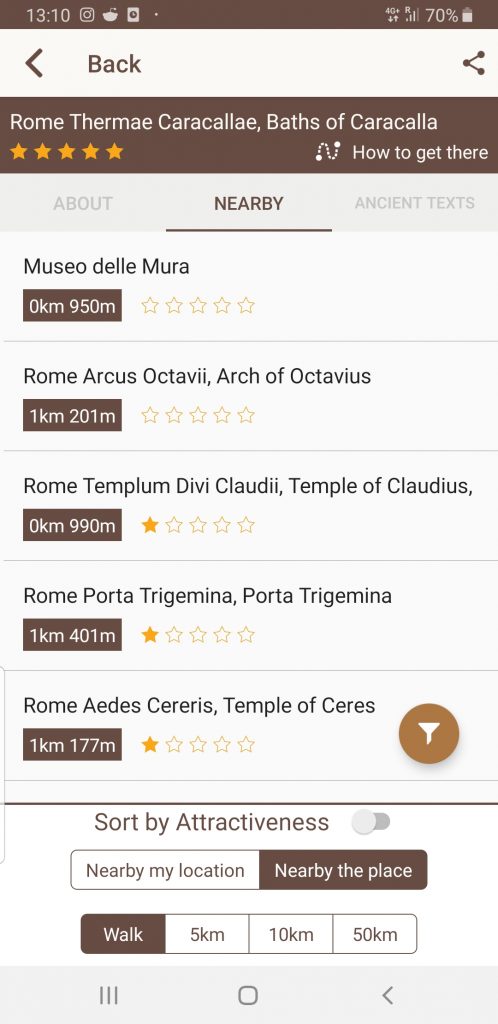

Caracalla Bath on Timetravelrome app:

To find out more: Timetravelrome.

Author: written for Timetravelrome by Michelle Richards. “What to see” text was written by Alexander Meddings.

Header photo: Panorama of the Baths of Caracalla, by Ethan Doyle White, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 .