“He stated that he had undertaken that campaign, not for his own occasions, but for the general liberty; and as they must yield to fortune he offered himself to them for whichever course they pleased — to give satisfaction to the Romans by his death, or to deliver him alive.”

– Julius Caesar, Gallic Wars

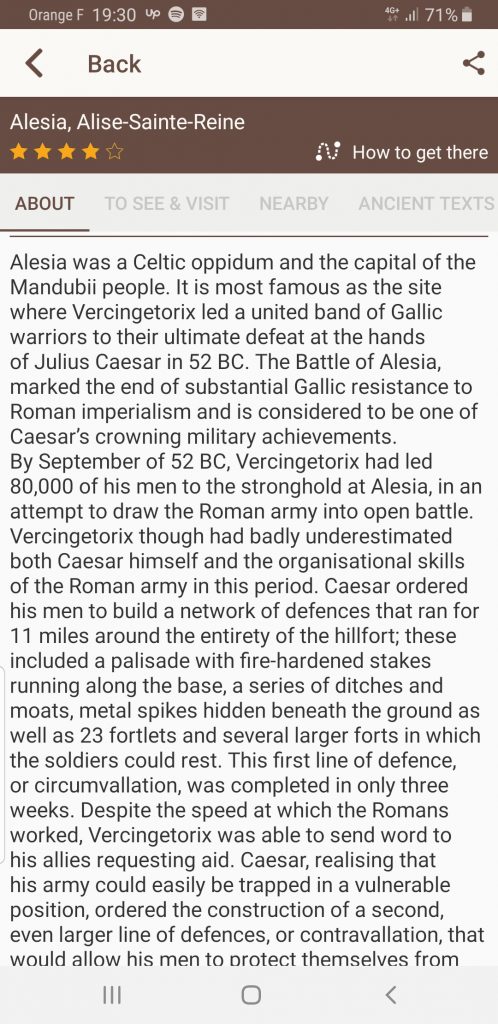

Alesia is little known besides its famous identity as the site of one of Julius Caesar’s greatest sieges. Today, the MuséoParc Alésia offers Gallo-Roman ruins, reconstructions of Caesar’s fortifications, and a beautiful new museum on site. Yet back in the middle of the 1st century B.C., Alesia was a major walled fort city. It served as the capital of the Mandubii tribe. Though Caesar had largely subdued Gaul, the local tribes were still eager to fight for their freedom. A brave warrior named Vercingetorix, Kin g of the Averni, staged the most successful rebellion. In 52 B.C., he faced one of Caesar’s ultimate innovations, the great circumvallation of Alesia.

Retreat to Alesia

Vercingetorix was under no illusions as to Caesar’s skill on the battlefield. For several months, he had been fighting a guerilla war against the Roman general. He even forced Caesar to withdraw from a siege of Gergovia, bolstering the spirits of the Gallic troops. However, their euphoria was short-lived. Soon after, the Gauls met with a heavy defeat in their first direct engagement with the Romans. Vercingetorix led his soldiers in a retreat to Alesia, continuing the scorched earth policy he had already instituted. They burned stored grain and farmland as they went, hoping to starve out the Romans and force their retreat. Arriving in Alesia, Vercingetorix closed the gates and trusted in the city’s natural and man-made fortifications for protection.

Caesar and his Roman legions soon arrived and set up camp around Alesia. Aware of the strong defenses, Caesar turned Vercingetorix’s plan back upon him, deciding to starve out the city. To do this, he set his industrious soldiers to building a new wall around the walls of Alesia. This tactic, called a circumvallation, was entirely new. The wall they built was ten miles long with twenty-four towers. Though the Gauls attempted a sortie to interrupt construction, their cavalry was repulsed. Before being completely walled in, Vercingetorix sent his own cavalry out with a desperate plea for reinforcements from the other Gallic tribes.

Digging in for Siege

To prepare for the arrival of the relief force, Caesar planned further fortifications. Behind their wall, his men dug three trenches of six meters deep, the third one filled with river water. Behind the trenches was a small fortification to protect his defending soldiers, with sharpened stakes facing the attackers. Yet that was still not the end of the defensive works built by the tenacious Romans. They dug eight rows of disguised pits, and sunk fire-hardened stakes as thick as a man’s thigh into the bottom. All around these traps, they scattered iron hooks and cattle trops. Finally, Caesar instructed his men to build yet another wall, called a contravallation, around the entire system of fortifications. Essentially, he was preparing for a siege within a siege.

Within Alesia, the Gauls were struggling. Vercingetorix had brought 80,000 soldiers into the city of 10,000 inhabitants, and food was scarce. The king personally rationed the supplies, but as the days passed and no reinforcements appeared, the situation became desperate. In a council, one of the King’s advisors suggested cannibalism. Luckily, the council rejected his idea, but their eventual solution was little better. They sent the women, children, old, and the sick out of the city, hoping that Caesar would take them captive and feed them. Yet Caesar and his forces were just as short on food, and Caesar would not allow the citizens through his wall. Instead, the families of the Gallic soldiers were stuck between the city walls and Caesar’s walls, braving the elements. Those still safely within Alesia could only watch as their families slowly starved to death between the two lines.

End of Gallic Independence

Upon the arrival of the Gallic reinforcements, the fighting began in earnest. Caesar claims to have had around 70,000 men fighting 248,000 Gauls. Other ancient sources claim as many as 400,000 enemy soldiers, but modern scholars are skeptical. However, the Romans were outnumbered significantly, likely fighting close to two Gauls for every one Roman. Caesar’s many fortifications proved successful. Vercingetorix and the encircled Gauls struggled to fill in the ditches and pits in order to join the fight. Meanwhile, the Romans were able to concentrate on fighting only one side at a time. Caesar’s legions were eventually victorious, and the relief force fled. Vercingetorix offered that his men should either kill him or offer him alive to appease Caesar. They surrendered him to the Romans, who held him captive for almost six years. In 46 B.C., he was paraded in Caesar’s first triumph and then executed.

Lionel Royer, in public domain.

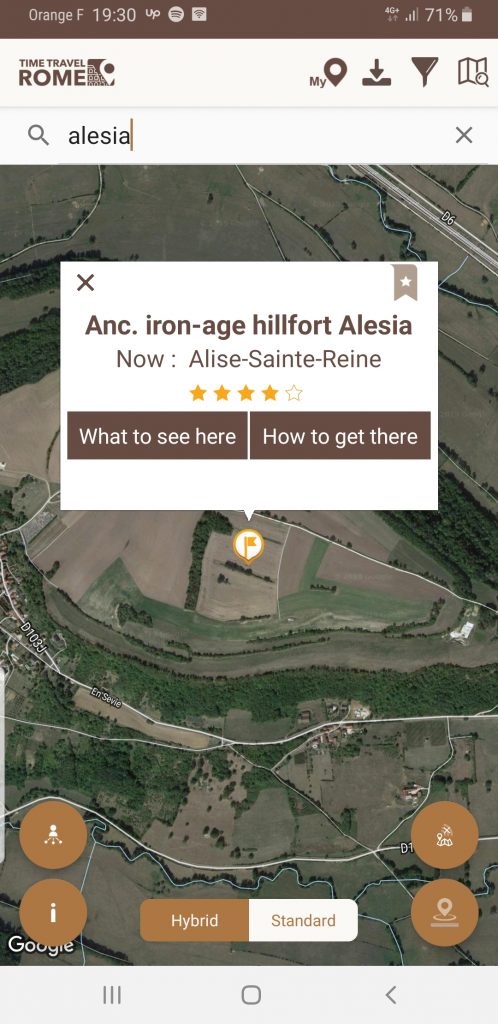

The location of Alesia was long debated, but is believed to be the Roman fort outside Alise-Sainte-Reine in France. Ancient sources long identified this site as Alesia, and a Gallic inscription in Latin characters also named the city. Excavations have revealed Roman fortifications from the Gallic Wars that are consistent with Caesar’s descriptions. Aerial photography reveals evidence of the systems of ditches dug by the Roman soldiers. Perhaps the most exciting discovery was a sling shot inscribed with the name of one of Caesar’s commanders, Labienus. Though some dissenting voices still suggest alternate locations, most historians and archaeologists are now in agreement as to the identity of Alesia.

What to See Here:

The modern town of Alise-Sainte-Reine lies at the foot of the ancient hill fort. Thankfully so, as it has been possible to excavate and preserve much of the Roman town at the top. Roman remains which have survived include paved streets with evidence of the shops that would have lined them. There is also a forum, the lower sections of a theatre and basilica, and several houses with well-preserved basements. The Monument of Ucuetis (a minor Celtic god, archaeologists found his name on an inscription in the building) is associated with the city’s metalworkers. Whilst a reasonable amount of the building survived above ground, its best feature is a beautifully preserved underground chamber.

Not ancient, but also of interest, is a large statue of Vercingetorix. It was built in 1865 as a symbol of French nationalism. In recent years, the entire hill fort and the fields surrounding it have been turned into the Musée Parc Alésia. This consists of a large museum and visitor’s centre. It also holds various Roman reconstructions, including a full-size 100m section of Caesar’s fortifications. The museum offers guided tours of the ancient site throughout the year.

Alesia on Timetravelrome app:

To find out more: Timetravelrome.

Author: written for Timetravelrome by Marian Vermeulen.

Sources: Julius Caesar, Commentaries on the Gallic Wars; Plutarch, Life of Caesar; Strabo, Geography.

Header photo: Alesia Fortifications by Prosopee licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0