“It is impossible for any good man to be born from me and this woman.”

– Nero’s Father about himself and Agrippina the Younger

The city of Baiae seems to have been one of the younger cities of Italy. A source from 178 B.C makes the earliest known reference to the city. Baiae takes its name from Baius, the Greek helmsman of Odysseus’s ship in Homer’s great epic poem. According to legend, Baius’s grave was near the city. By the end of the Republic, the city had become a popular resort town for Rome’s elite. Marius, Lucullus, Pompey, and Julius Caesar all maintained villas there, as did many of the Roman emperors. Baiae’s reputation was not only for opulence and luxury, but also depravity, promiscuity, and scandal. It was a particular favorite of the Emperor Nero. In 59 A.D., Nero plotted the murder of his mother, Agrippina the Younger, at Baiae.

Five Good Years

Agrippina herself was hardly an innocent martyr, but rather cunning, ambitious, and ruthless. She was willing to do whatever it took for her family to hold power. Her only natural son was Nero, the product of her first marriage. She married the Emperor Claudius, her uncle, even though the people of Rome strongly disapproved of the incestuous match. She quickly began working against Britannicus, Claudius’s young son from a previous marriage. Before long, Claudius supported Nero as the intended heir. Shortly after, when Nero was seventeen, Claudius died suddenly. Suspicion fell immediately on Agrippina, though unproven. The Praetorians hailed Nero as the new emperor. Though some wondered where Britannicus was, they accepted the candidate presented with little dissent.

Nero’s first years of rule went well. He seemed to be everything the Senate and people of Rome could wish. Nero honored his deceased uncle, delivering a eulogy penned by Seneca. He fulfilled his duty by humbly requesting that the Senate deify Claudius. In his speech to the Senate, he paid deference to their importance to government, distanced himself from several unpopular decisions, and praised the structure of the Republic. Flattered and pleased, the Senate ordered the speech inscribed on a silver column and read annually. Perhaps it was partly praise for the speech and partly a reminder to Nero of his promises. Nero did keep them, at least for those five years. He showed mercy to opponents, established strong colonies, and took on many civic projects. When the Senate offered him an official vote of thanks, he refused, saying “wait until I have earned them.”

Tensions Rise

Some of this early success might be the result of his advisors, Seneca, Burrus, and of course his mother. She shared space with Nero on coins minted in his honor, appearing as an equal and almost implying co-emperorship. The Senate forbade women to enter its halls; so Senators and government officials often met Nero at the palace. Agrippina could not directly participate, but stood at a doorway behind a small curtain, specially made for her use. She was so comfortable with her place in Nero’s council that she almost disgraced him badly before foreign envoys. A group of Armenians had come before Nero to make a plea. Agrippina entered the hall and headed for her son’s dais, prepared to preside over the meeting with him. All froze, except for Seneca. Thinking quickly, he whispered to Nero to go down and meet his mother, and kindly re-direct her.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ner%C3%B3n_y_Agripina.jpg

They avoided causing insult, but the incident proved a turning point in the relationship between mother and son. Nero distanced himself from Agrippina, and Seneca and Burrus took over her role as his chief advisors. The resulting coolness created tension between them. It eventually escalated into an open fight, with Agrippina shouting abuse at her son, and declaring that Britannicus, her step-son, was the rightful and worthy heir to the throne. She threatened to use her influence to sway the Roman legions to support of Britannicus. It was an ironic shift of loyalty for Agrippina, who had greatly mistreated Britannicus when he was only a boy of around ten or twelve. She had practically imprisoned him in his own room and kept him from seeing his father. Nero obviously did not take the threat lightly, and arranged the poisoning of Britannicus.

Murder at Baiae Bay

Nero became increasingly paranoid after the murder. Seneca and Burrus still tempered him some, but were most concerned with their own safety. Rightfully so, for eventually they were both implicated in plots. Seneca committed suicide rather than face execution by his former student. Without their steadying influence, Nero became even wilder, ordering many executions, including that of his wife, Octavia, sister of Britannicus. Eventually, he decided it was time to rid himself of the shadow of Agrippina. He went to his seaside villa at Baiae, and invited his mother to join him, feigning a desire for reconciliation. On the way into the bay, a convenient accident resulted in Agrippina’s boat being rammed, causing significant damage. After dinner, Nero offered her one of his vessels for the return journey to her coastal villa.

As the ship headed out into the bay on a tranquil sea, it suddenly collapsed from the top down. Inspired by a theater performance, Nero’s former tutor, Anicetus, had designed the ship for Nero’s plot. Yet Agrippina escaped the disintegrating vessel, swam ashore and made it to her villa. She realized the truth, but pretended not to, sending a messenger to innocently inform Nero of his mother’s safety. Nero framed the messenger, and sent Anicetus to finish the job. When he arrived, Agrippina knew why he had come. She leapt up, tore open the clothes over her stomach, and said “strike me in my womb, Anicetus, because this was what bore Nero.” Nero soon felt the guilt of his deed. He spent many sleepless nights, terrified of any noises coming from the direction of Agrippina’s tomb, and admitted that he felt forever pursued by her ghost.

What to See Here?

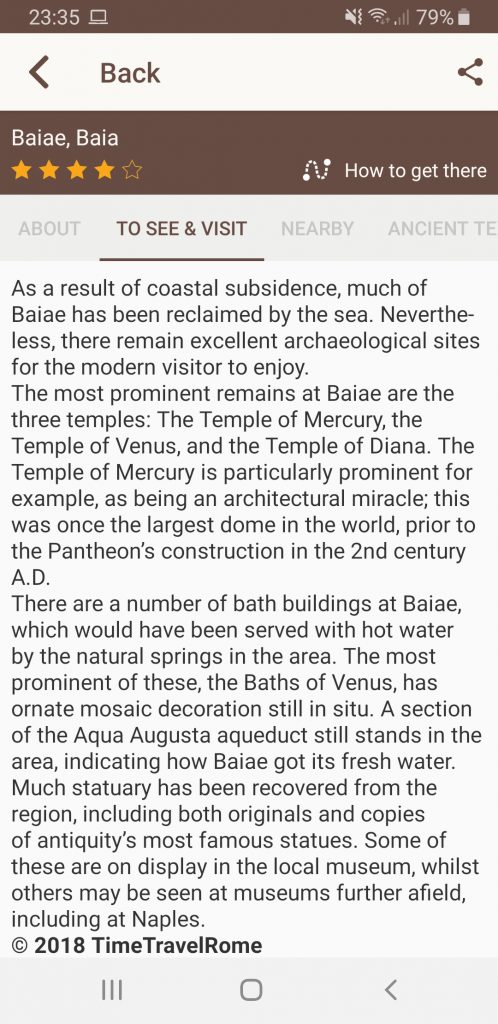

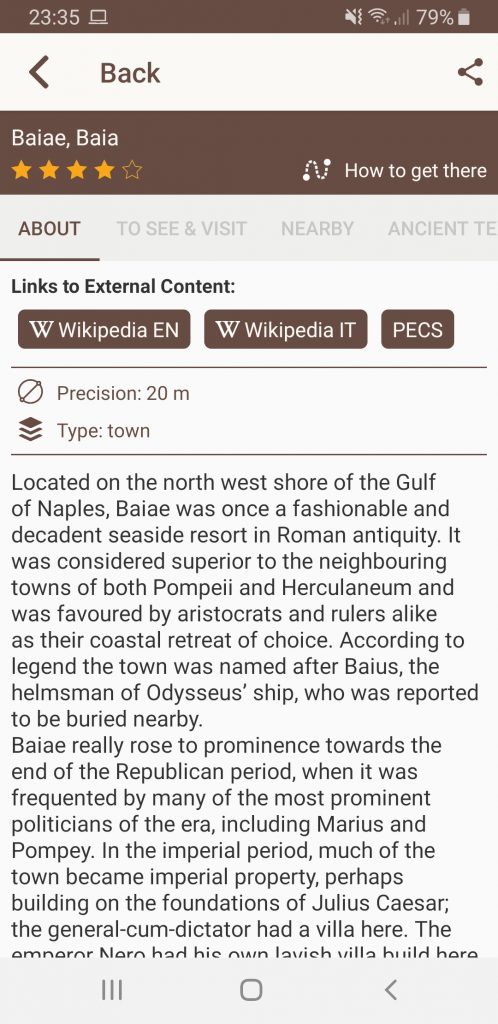

As a result of coastal subsidence, the sea has reclaimed much of Baiae. Nevertheless, there remain excellent sites for the modern visitor to enjoy. The most prominent remains at Baiae are the three temples: The Temple of Mercury, the Temple of Venus, and the Temple of Diana. The Temple of Mercury is particularly prominent for example, as being an architectural miracle. This was once the largest dome in the world, prior to the Pantheon’s construction in the 2nd century A.D.

There are a number of bath buildings at Baiae, which would have been served with hot water by the natural springs in the area. The most prominent of these, the Baths of Venus, has ornate mosaic decoration still in situ. A section of the Aqua Augusta aqueduct still stands in the area, indicating how Baiae got its fresh water. Archaeologists have recovered much statuary from the region, including both originals and copies of antiquity’s most famous statues. Some of these are on display in the local museum, whilst others are at museums further afield, including Naples.

To find out more: Timetravelrome.

This article was written for Time Travel Rome by Marian Vermeulen.

Sources: Cassius Dio, Roman History; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews; Seneca, De Clementia; Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars; Tacitus, The Annals

Header Photo: Jan Styka – Nero at Baiae by Jan Stykais licensed under CC0