Memphis was established as far back as 3000 B.C., legends say by the pharaoh Menes. It soon became the capital of ancient Egypt, and remained so for centuries. In 332 B.C., Alexander the Great and his Macedonians marched into the city. The Egyptians, subjugated by the Persians for years, welcomed them as liberators, and officially crowned Alexander as their pharaoh. While in Egypt, he took a pilgrimage to Oracle at Siwah, and developed a great affinity for Egypt. His general and friend, Ptolemy, traveled with him, and learned of Egypt’s strategic and economic capabilities. Years later, Ptolemy would face down Perdiccas at a tragic battle across the Nile River at Memphis.

Heist of the Millennium:

Not ten years later, Alexander the Great was dead in Babylon with no heir to take his throne. His many generals vied for control in the power vacuum that followed. They divided the satraps, or provinces, that they had conquered over the years among themselves. Ptolemy, ever a shrewd player, opted to take Egypt. Despite its rich resources, it was far from their ancestral heartland of Macedonia in Greece, and therefore considered unimportant. Ptolemy withdrew to the capital of Memphis and slowly began to build his strength and wealth.Yet in 321 B.C., he made a bold move that propelled Egypt to the center of the struggle.

Alexander’s body had lain embalmed in Babylon for almost two years, waiting for the completion of an ornate golden sarcophagus and massive carriage to carry him back to Macedonia. As the funeral procession, at last underway, moved through Damascus, Ptolemy intercepted it and hijacked the body of Alexander. He brought the king’s body to Memphis, and laid him to rest in the Temple of Ammon. The theft kicked off the First War of the Diadochi. Trouble had already been brewing between Ptolemy and Perdiccas, the regent of Macedonia. After the theft, Perdiccas tried to hold a show trial to condemn Ptolemy to death. Yet the soldiers were deeply fond of Ptolemy, who was “modest and unassuming … superlatively generous and approachable.” They instead voted to acquit.

Attack on Egypt:

Nevertheless, Perdiccas marched on Egypt, with a large army of infantry, cavalry, and even war elephants. He first attempted to cross the Nile at the Ford of Camels, but Ptolemy had fortified the fortress there. The soldiers set up ladders to scale the walls, while the elephants began tearing apart the wooden palisades. Ptolemy had his best men with him in the vanguard of his army. Hoping to encourage his soldier, he rushed to the point where the fighting was thickest. Grabbing a long spear, he blinded the lead elephant, then attacked the men scaling the walls with reckless courage. His men followed his example, and rushed boldly into the chaos. After an exhausting day of fighting, Perdiccas eventually withdrew his men. Rather than resting, however, he led a quick march downstream toward Memphis, where a small island divided the large river.

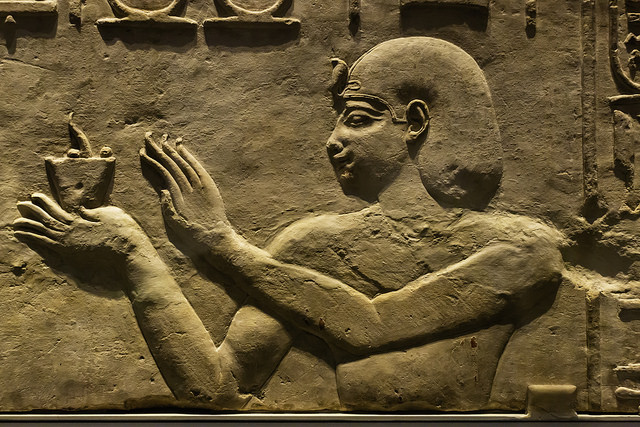

Piece of column of the Merenptah’s palace in Memphis, by Neithsabes is licensed under Public Domain

Hoping for surprise, he dispatched the attack at the first light of dawn. The first soldiers managed to get to the little island, but the water was deep. They were almost swept away by the strong current. Trying to make the crossing easier for his men, Perdiccas sent his elephants upstream in the river, and his horsemen downstream. He hoped the elephants would provide a break in the current, while the horsemen could catch any soldiers who needed it. The animals waded into the river, disturbing the mud and silt of the riverbed, which only deepened the channel between. The soldiers in the river panicked, believing Ptolemy had some kind of sluicegate upstream that he had opened to flood them. Those that could still manage it scrambled to the nearest solid land, and Perdiccas stopped the crossing.

Catastrophe at the Crossing:

The men who had made it to the island began to worry. If Ptolemy attacked them, they weren’t enough to defend themselves, but the river was still running strong and fast. Reluctantly, they threw away their weapons and armor. It was their own gear that they had carried and protected for more than ten years of campaigning. However, they had no choice. Free of their burdens, they leapt back into the water. Those who could swim managed to navigate the swirling waters, but many did not. Flailing and drowning, they caught the attention of other residents of the water. Hordes of Nile crocodiles arrived, feeding at will on both bodies and those still living and struggling to reach the safety of the shore. Their friends watched helplessly from the banks as their comrades were torn to pieces and the Nile ran red with blood.

The assault was a disaster, the river littered with mangled corpses. Over two thousand men died, whether by drowning or crocodiles. Some ancient historians even claimed that Perdiccas lost more men in the river than Alexander had in his years of campaigning. As Perdiccas’s men sat around their camp that night, they saw Ptolemy and his men on the other bank. They were reverently gathering the dead, despite being their enemies, and burying them will full rights and honors. Infuriated by the loss of life and disillusioned with Perdiccas’s command, three of Perdiccas’s senior officers, Pithon, Antigenes, and Seleucus, snuck into his tent that night and stabbed him to death.

Nile river by Limboko is licensed under Public Domain

Ptolemy’s Legacy:

Ptolemy remained in Egypt for the rest of his life. He moved the capital of Egypt to Alexandria; the port city founded by

Sources: Diodorus, Library of History; Strabo, Geography

This article was written for Time Travel Rome by Marian Vermeulen.T

Photo: Relief of Ptolemy I Making an Offering to Hathor by Thad Zajdowicz

is licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0)

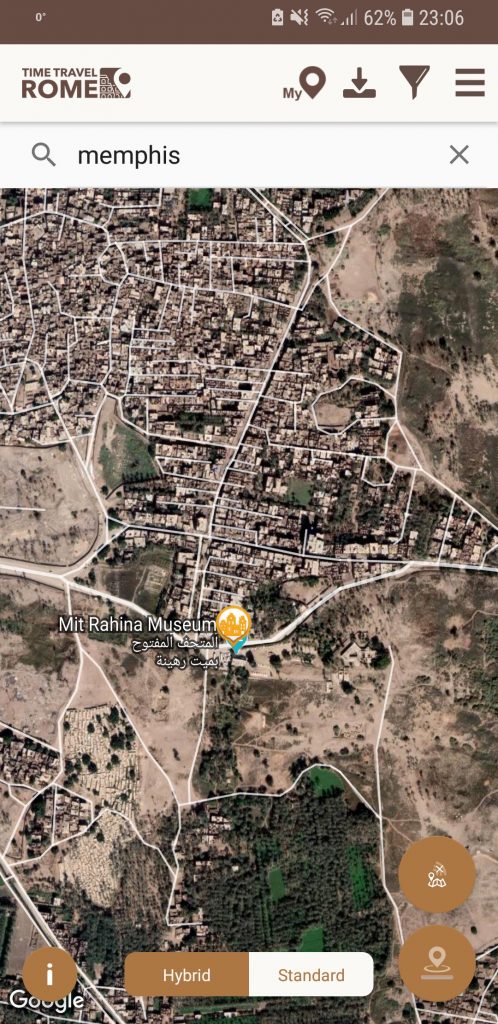

What to see Here:

The ancient city of Memphis has been under conservation as a world heritage site since 1979 and is today an open-air museum. It boasts considerable temple remains, the most important being the Temple of Ptah first mentioned by the ‘father of history’ Herodotus. Many remains from the temple have been shipped off to museum collections around the globe. A decent repository, however, can be found in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum. Within this enormous temple complex, archaeologists have uncovered the remains of what they believe to be the Temple of Apis: the bull manifestation of Ptah. It is described by the geographer Strabo, who accompanied conquering Roman soldiers there after Octavian’s victory over Antony and Cleopatra at Actium (31 BC). The only other significant Roman era site is a temple to Mithras, discovered by accident along with 11 statues in 1837 just north of Memphis.

To find out more: Timetravelrome.