Michel Gybels for Timetravelrome

Tropaeum Traiani: A Testament to Roman Glory in Ancient Dacia

Rising from the windswept plateau of Adamclisi in Romania’s Dobruja region, the reconstructed Tropaeum Traiani stands as one of the most remarkable testimonies to Roman imperial ambition and military might. This magnificent circular monument, commissioned by Emperor Trajan in 109 CE, commemorates not just a victory, but the brutal reality of conquest that shaped the ancient world.

Metopes on the Tropaeum Traiani monument. Photo by Michel Gybels.

The Historical Context: Trajan’s Dacian Wars

The story of Tropaeum Traiani begins with one of the most decisive conflicts in Roman history—the Dacian Wars (101-106 CE). The monument specifically commemorates the victory at the Battle of Adamclisi in the winter of 101-102 CE, where Emperor Trajan faced the Dacian king Decebalus in what would prove to be a pivotal confrontation. The battle was particularly brutal, with heavy casualties on both sides, though it ultimately resulted in a decisive Roman victory.

The battle arose from Decebalus’s strategic gambit to attack Roman-held Moesia south of the Danube, hoping to force Trajan to abandon his positions near the Dacian capital of Sarmizegetusa. The Dacian army, allied with the Roxolani and Bastarnae tribes, attempted to cross the frozen Danube but suffered massive losses when the ice broke under their weight. Trajan moved his army from the mountains, following the Dacians into Moesia, where the decisive engagement unfolded at Adamclisi.

Architectural Marvel: Engineering Roman Glory

The Tropaeum Traiani was likely designed by Apollodorus of Damascus, Trajan’s favored architect who also engineered the famous bridge across the Danube. Standing approximately 40 meters tall with an equal diameter, the structure embodies the Roman mastery of monumental architecture. The monument consists of a massive cylindrical drum built on seven concentric rows of stone steps. The drum itself was constructed of concrete (opus caementicium) faced with local limestone blocks, arranged using the sophisticated opus quadratum technique without mortar—a method showing Greek influence adapted to Roman engineering standards.

Tropaeum Traiani. Photo by Michel Gybels.

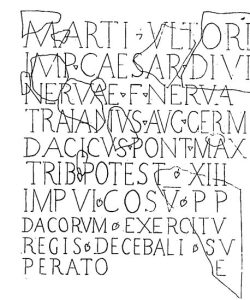

The structure was dedicated to Mars Ultor (“Mars the Avenger”), with a bilingual inscription preserved fragmentarily on the hexagonal base: “MARTI ULTOR[I] IM[P(erator)CAES]AR DIVI NERVA[E] F(ILIUS) N[E]RVA TRA]IANUS [AUG(USTUS) GERM(ANICUS)] DAC]I[CU]S PONT(IFEX) MAX(IMUS) TRIB(UNICIA) POTEST(ATE) XIII IMP(ERATOR) VI CO(N)S(UL) V P(ater) P(atriae),” translating to “To Mars the Avenger, Caesar the emperor, son of divine Nerva, Nerva Trajan Augustus, Germanicus, Dacicus, Pontifex Maximus…”

Reconstruction of the inscription.

The Metopes: Visual Chronicles of Conquest

The monument’s most striking feature was its frieze of 54 rectangular stone panels (metopes) that encircled the drum like a belt, each measuring approximately 1.48-1.49 meters in height.

Metopes on the monument. Photo by Michel Gybels.

These metopes depicted scenes from the Dacian Wars in remarkable detail, from cavalry charges to hand-to-hand combat.

Metopes – a closer view. Photo by Michel Gybels.

Of the original 54 metopes, 48 survive and are housed in the Adamclisi Museum, while one is preserved in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. The remaining few were lost over time, with some reportedly falling into the Danube during attempts to transport them to Bucharest.

Roman Legionary with a mail manica and spear with Dacian falxman. Photo by Michel Gybels.

The metopes narrate the progression of war, beginning with cavalry action and heavy fighting, including five scenes of hand-to-hand engagement between Roman legionaries and their Dacian opponents. The narrative includes depictions of Trajan himself, Roman soldiers on the march, brutal battle scenes, and the final subjugation of the Dacian prisoners.

Vexilliferi (Standard Beareres). Photo by Michel Gybels.

The metopes were created by five different groups of craftsmen, each with varying levels of skill—some carved human sculptures clumsily, while others demonstrated sophisticated knowledge of human proportions. Unlike the refined depictions on Trajan’s Column in Rome, these metopes have been described as displaying “barbarian provincial taste,” carved by “sculptors of provincial training” who “reveal a lack of experience in figurative representation.” However, this rawer, bloodier art carries “more power and authenticity for lacking the filter of a refined disdain for the realities of war.”

Legionary and Dacian Warrior. Photo by Michel Gybels.

The simplified nature of the reliefs may have been deliberately designed to clarify imperial iconography for a provincial or foreign audience. As scholar Jas Elsner noted, the reliefs present all the “vitality, vigour and non-classicism of barbarian art,” giving the conquered Dacians a “visual voice” in the narrative that was “familiar, even natural” to them.

Barbarian family in a four-wheel cart. Photo by Michel Gybels.

Destruction and Rediscovery

The monument’s fate mirrored the empire’s own decline. By the second and third centuries CE, it suffered degradation from earthquakes and human activity. In 170 CE, the citadel of Tropaeum Traiani faced attacks from the Goths, and the monument may have been destroyed in an earthquake by 316 CE. A great earthquake in 477 CE further damaged the structure, causing it to lean, as discovered by later topographic surveys.

With the rise of Christianity, the monument faced deliberate destruction as local inhabitants, who “still shared the pagan philosophy,” attacked “the ancient cults represented by sculptures and images.” The process was similar to that experienced by the Tropaeum Augusti in France, where Saint Honoratus initiated the demolition of statues considered pagan idols. The scattering of fragments occurred between the fifth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century. During this time, after the Ottoman empire established its capital in Constantinople in 1453, a Turkish general visited the site and extracted a sculpted metope to send to Constantinople.

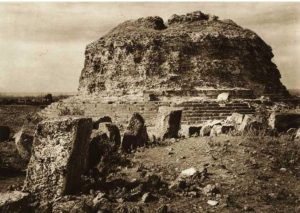

Tropaeum by H. Jacobi in 1896, Public Domain

By the 19th century, the monument appeared as “a huge dome-shaped masonry surrounded by massive deposits of earth and debris, where shrubs had grown, among which were carved stones scattered about.” The first modern archaeological investigations began in 1882 under Grigore Tocilescu, the first Romanian archaeologist, who conducted campaigns in 1883, 1884, and 1890.

Tropaeum Traiani at Adamclisi, before its reconstruction in 1977. Source: Remembering victories, remembering losses: Trajan’s Trophy and Altar at Adamclisi.

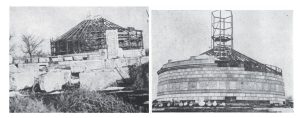

After extensive debates in the 1960s, Romanian authorities chose to rebuild the monument using new materials while preserving the original pieces in museums. Two solutions were proposed: restore the original pieces to Adamclisi and reconstruct the missing ones, or keep the originals in Bucharest’s History Museum and create copies. The second option was approved, and reconstruction began in 1973, completed in 1977 to coincide with the centenary of Dobrogea’s union with the Romanian state.

Reconstruction works. Source: Tropaeum Augusti (France) and Tropaeum Traiani (Romania): A Comparative Study

The new monument uses a metal structure clad with stone pieces from the same ancient quarries exploited 2,000 years ago, located in the Enigea valley about 4 kilometers from Adamclisi. This approach maintained the monument’s visual impact while preserving the authentic artifacts for posterity. The reconstruction follows the same architectural principles as the original, including the cylindrical base, conical roof with scale-like stone plates arranged in 25 concentric rows, and the hexagonal superstructure supporting the trophy.

Military and Strategic Importance

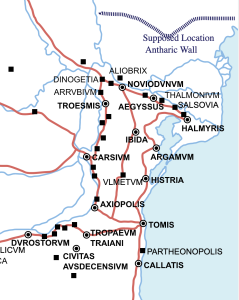

Tropaeum Traiani was positioned at a crucial strategic location, controlling the ancient road from Tomis (modern Constănţa) to Durostorum (modern Silistra in Bulgaria). This positioning made it not merely a commemorative monument but a statement of Roman territorial control and a warning to potentially rebellious tribes. Trajan settled veterans from his Dacian campaigns in the area, establishing both a fortress and a civil town. The inhabitants, known as the “Traianenses Tropaeenses,” dedicated a statue to their patron emperor between 115-116 CE.

Cities and roads in eastern Moesia, by CristianChirita, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Under Antoninus Pius, the site became home to a detachment of the XI Claudia legion, and its importance grew when it was promoted to the rank of municipium around 180 CE during Marcus Aurelius’s reign. However, the settlement’s exposed position meant it did not prosper during the 3rd century and had to be rebuilt almost from scratch during the time of Constantine the Great and Licinius. A dedication survives to the two emperors, with Constantine tellingly taking precedence. The settlement continued until it was destroyed by the Avars at the end of the 6th century, marking the end of nearly five centuries of Roman presence in the region.

Comparison with Tropaeum Augusti: Two Monuments, One Empire

The Tropaeum Traiani shares striking similarities with its French counterpart, the Tropaeum Augusti at La Turbie. Both monuments celebrate imperial victories over frontier peoples—Augustus over 45 Alpine tribes in 6 BCE, and Trajan over the Dacians in 102 CE. Both use circular architecture with metopes and pilasters, were built according to Vitruvian principles, and served as symbols of Roman territorial control in conquered regions.

La Turbie – reconstruction. Photo by Von Matthias Holländer.

Key differences exist in their current states: Tropaeum Augusti preserves original ancient construction consolidated but incomplete, while Tropaeum Traiani presents a complete reconstruction using new materials. The La Turbie monument stands 35 meters high and retains much of its original stonework, while partial reconstruction allowed only the western facade to be completely restored. In contrast, the Adamclisi monument was entirely rebuilt with copies to preserve the originals in museums.

La Turbie – photo by Von I, Gugerell, CC BY 2.5.

The Adamclisi Museum: Preserving Ancient Testimony

The modern museum, designed as a lapidarium to shelter and promote the original sculptural pieces, houses the authentic metopes carefully arranged and numbered according to their presumed placement on the monument. Beyond the 48 preserved metopes, the museum displays the lower and upper friezes, pilasters, crenelations, parapet blocks from the figured attic, and the colossal statue of the trophy with preserved elements of the statuary group—Geto-Dacian women and captives with hands bound.

Museum. Photo by Michel Gybels.

The museum also contains fragments of the dedicatory inscription and remains from the altar bearing the names of approximately 3,800 fallen Roman soldiers. Archaeological artifacts from the nearby city of Tropaeum Traiani and surrounding areas illustrate both the early habitation of the Geto-Dacians in southern Dobrogea and the continuity of Romanian settlement in this region where Romanization occurred most profoundly.

Museum. Photo by Michel Gybels.

The Site of the Ancient Town

The remains of the ancient town lies just a couple of kilometers away from the actual village, on a low rise from which a fantastic view can be had of the trophy itself and on to the high plateau up to the east.

Civitas Tropaensium – by Rotaru Florin – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

It is protected on three sides by a natural slope, which was reinforced in the 4th century by a defensive wall studded with horseshoe-shaped towers. Here and there the ground is scarred with the trenches from various archaeological campaigns.

Remains of the ancient walls. Photo by Michel Gybels.

On the town’s main street, around 200 metres from the principal gate, lies the basilica forensis, the civilian basilica, marked out by two rows of column bases that formed the portico of the building.

Columns of the Basilica. Photo by Michel Gybels.

The forum, alongside which the basilica must have lain, is obscured by a jumble of ruins. Nearby, four Christian basilicas from the 4th to 6th centuries are evidence of the Christian life of the city. One, the ‘Cistern Basilica’, was adapted in late-Roman times from a pre-excisting water cistern, which provided a convenient and well-built rectangular structure without the need for extensive new building. Across the main street again are the ruins of the ‘Marble Basilica’, clear only from the shape of its apse, the rest being just an undifferentiated mass of stones.

View on the archaeological site. Photo by Michel Gybels.

The east gate of the city and the adjacent wall have been reconstructed and one tower stands incongruously whole. Leaving the site from the south side, a single jagged arch of a gateway survives, divorced from any surviving stones of the walls, from where a slight scramble leads down to the modern roadway.

Reconstructed tower. Photo by Michel Gybels.

Legacy and Significance

The Tropaeum Traiani stands as more than a monument to military victory; it represents the complex relationship between conqueror and conquered, between imperial ambition and human cost. Its brutal imagery depicts not just Roman triumph but “the subjugation of a nation and the ugliness of war, made all the more unsavoury for its triumphalist tone.” Yet from the Roman perspective, they had merely punished treaty-breakers and brought “peace” to a new province.

The monument exemplifies how Rome used architecture as political propaganda, creating permanent reminders of imperial power that would outlast the battles themselves. The choice to erect such a massive structure in conquered territory, rather than in Rome itself, demonstrates the importance of projecting strength to both subjected populations and potential enemies. The inclusion of local artistic traditions in the metopes suggests a nuanced approach to cultural integration, allowing the conquered some representation in their own subjugation.

*The Tropaeum Traiani can be visited freely, while the Victory Monument and archaeological museum in Adamclisi require admission tickets. The site offers a profound glimpse into the ambitions, achievements, and ultimate limitations of one of history’s greatest empir

Sources:

“Tropaeum Augusti (France) and Tropaeum Traiani (Romania): A Comparative Study” by Alexandru Ș. Bologa and Ana-Maria Grămescu.

“La propagande impériale aux frontières de l’empire romain: Tropaeum Traiani” by Maria Alexandresca Vianu.

“Inscriptii de la Tropaeum Traiani“. Heidelberg University.

Header photo: By Andrei Lucian Vaida – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.