Written for Timetravelrome by Michel Gybels

The god Mithras originated in Persia but was recovered by the Romans. For more than three centuries the cult was an overwhelming success throughout the Roman Empire, attracting thousands of followers between the first and fourth centuries of our era. More recently, sanctuaries have been discovered at Ostia in Italy, Mariana in Corsica, Kempraten in Switzerland, Alba Iulia in Romania and Inveresk in Scotland. Modern scientific research now throws a whole new light on this ancient cult.

Pictures used in this article were taken by Michel Gybels at the Royal Museum of Mariemont (Belgium), where a very interesting exhibition “The Mithras Mystery…immersion in a Roman cult” will run until 17 April 2022. Afterwards, this exhibition will travel to the Musée Saint-Raymond in Toulouse (France) and to the Archaeological Museum in Frankfurt (Germany).

The Mithras cult: a recent rediscovery ?

From the 15th century, or even earlier, Renaissance humanists rediscovered the texts and material remains of Roman antiquity. Excavations in Rome brought the first Mithraic finds to light, particularly the spectacular reliefs showing Mithras slaying the bull.

Restored Mithras altar. From the Mithras exhibition at the Royal Museum of Mariemont (Belgium). Photo by Michel Gybels.

These finds stirred the imagination and many soon ended up in the antiquities collections of the great aristocratic families of Rome, such as the wealthy Ludovisi or Borghese families. These finds were carefully inventoried and identified, and then included in erudite collections such as Vincenzo Cartari’s Les images des dieux (1571). More than a century later, these reliefs were still depicted in illustrated encyclopaedias, such as L’Antiquité expliquée by Bernard de Montfaucon (1719).

These collections produced the first important theories about the origins of Mithras and the nature of his cult. Sometimes he was considered an agricultural deity, sometimes a sun and creation god from Persia. His cult was already described as a secret mystery cult with communities of men who underwent certain ordeals during initiation rites.

Mithras slaying a bull. From the Mithras exhibition at the Royal Museum of Mariemont (Belgium). Photo by Michel Gybels.

The interest in Mithras gained momentum at the beginning of the 19th century when new archaeological discoveries were made and the first temples were excavated in the Roman provinces. In Germany, two mithraea were discovered in 1826 near Frankfurt in the district of Heddernheim on the site of ancient Nida. Many other remains were excavated on the Limes along the borders of the Empire, along the Rhine and Danube.

The decisive impulse for modern research was given in Belgium by the historian of religion Franz Cumont (1868-1947). Cumont found himself at the heart of a large scientific network that he had built up himself. He travelled extensively and reported extensively on his findings. In his Textes et monuments figurés relatifs aux mystères de Mithra, he collected all written and material sources on Mithras in two volumes (1896 and 1899). The subsequent synthesis work Les mystères de Mithra (1900) became the worldwide reference on this subject.

Mithraeum in Halberg, Germany. Photo by Timetravelrome. Full Flickr album. (CC BY 2.0)

Cumont’s insights remained leading in the scientific world until the 1970s. One of these theories was that the Roman images of the Mithras cult referred to a myth of origin that had its roots in the East, especially in Iran. In 1933-1934 the extraordinary mithraeum of the border town of Doura-Europos in Syria was discovered and excavated on the banks of the Euphrates. This seemed to confirm Cumont’s analysis.

Although these theories have been critically evaluated, refined and sometimes contradicted in recent years, Cumont’s research has definitely paved the way for the modern study of Mithras.

Mithras sculpted group. From the Mithras exhibition at the Royal Museum of Mariemont (Belgium). Photo by Michel Gybels.

Why does Mithras kill a bull ?

The Romans inserted the story of Mithras into a broader mythological framework known to all. This served as a kind of introduction, after which the adventures of the god followed, from his earthly birth to his cosmic apotheosis.

Just when Jupiter has become the victor in the devastating war between the gods of Olympus and the Giants, destruction strikes on earth. Phaëton, the son of the sun god Sol, loses control of the sun chariot entrusted to him by his father. This clumsiness destroys the earth and disrupts the cycles of the stars. Jupiter strikes him down and summons the gods to find a solution to the chaos caused. A hero is appointed to restore order: Mithras.

Terracotta Mithras relief. From the Mithras exhibition at the Royal Museum of Mariemont (Belgium). Photo by Michel Gybels.

Mithras is born on earth naked and only wearing a Phrygian cap by wriggling himself out of a rock (Mithras petrogenes). He is helped by two shepherds, the twins Cautes and Catopates, who become his companions. In his hands he already holds a sword and a torch, attributes for his future heroic deeds.

Mithras begins his heroic deeds by shooting an arrow at a rock, from which a spring of water springs up to irrigate the earth again and thus free it from drought. All that is missing to complete the regeneration of the world is the life force contained in a fabulous bull.

Mithras goes in search of the animal grazing in the mountains, drives it from its hiding place by setting it on fire, overpowers the bull and finally carries it on his shoulders to a cave. There Mithras is met by a raven sent by Sol. The raven conveys to him the command of the gods to kill the bull. Mithras grabs the animal and pierces its chest with his sword. The life force of the bull spreads and regenerates the earth. The zodiac and the planets regain their usual place in the universe.

Sol, however, is jealous of Mithras’ success and a conflict arises between the two gods. In battle, Mithras soon gains the upper hand and the defeated sun god pledges his allegiance by laying his halo at his feet, but Mithras returns it. The two gods shake hands over a burning altar and thus the pact between the former rivals is sealed.

Bust of Sol. From the Mithras exhibition at the Royal Museum of Mariemont (Belgium). Photo by Michel Gybels.

Sol and Mithras, who now bears the title Sol Invictus (the invincible Sol), celebrate their new alliance with a banquet at which they eat the flesh of the bull and drink its blood. Then they ascend to heaven in the quadriga of the sun god.

Sol and Mithras banquet. From the Mithras exhibition at the Royal Museum of Mariemont (Belgium). Photo by Michel Gybels.

These successive episodes tell a chronological story of the world in which Mithras eventually becomes the one responsible for the cosmic and worldly order: he is the one who restored the cycle of the stars over time. The myth had different versions and explanations, depending on the place, time and community of followers.

Restored relief representing the banquet of Sol and Mithras. From the Mithras exhibition at the Royal Museum of Mariemont (Belgium). Photo by Michel Gybels.

Was Mithras Defeated by Christ ?

For a long time, the disappearance of the Mithras communities has been attributed mainly to the triumph of Christianity over pagan cults. This view is based on the polemical writings of some Christian authors who brand the Mithras cult as the work of the devil because of its alleged similarities to Christianity. These literary exploits have fed the idea that the Mithras sanctuaries were deliberately destroyed by the Christians in order to build their churches on them.

Mithras temple – reconstruction. From the Mithras exhibition at the Royal Museum of Mariemont (Belgium). Photo by Michel Gybels.

However, recent archaeological research shows that the situation is more complex and presents a more nuanced picture. The imperial edicts prohibiting the practice of pagan cults at the end of the fourth century certainly played a role, but the disappearance of the Mithras cult was not solely due to the Christians.

The Mithras cult was not officially recognised by the Roman authorities and received no public subsidies. From the second century onwards, some sanctuaries were abandoned due to the death of the community leader, relocations, financial difficulties, military conflicts and even natural disasters.

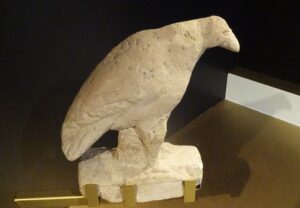

Raven – messenger sent to Mithras by Sol. From the Mithras exhibition at the Royal Museum of Mariemont (Belgium). Photo by Michel Gybels.

However, some Mithras communities continued to exist until the end of the fourth century or even the beginning of the fifth in an empire that was now officially Christian. In the cities, all kinds of abandoned or decommissioned buildings were eventually reused as Christian places of worship. When excavations were carried out under Roman churches to determine their origin, the existence of original mithraea came to light. The best known example is that of San Clemente in Rome. There, on top of a Mithra temple from the end of the second century, an early Christian basilica was built in the fourth century and a church on top of it in the twelfth century. But it seems that no Mithras sanctuary was ever directly converted into a church.

The images of the pagan gods were also removed. In the Mithras Cave in Dülük, Turkey, the reliefs were chiselled away and even a cross was placed on top of Mithras’ face. From the fifth century onwards, the god and his cult gradually disappeared from the collective memory until Renaissance scholars rediscovered him.

Mithras relief in the Musée de La Cour d’Or of Metz. Picture by Timetravelrome. Full Flickr album. (CC BY NY).

In 1882, the French Orientalist Ernest Renan wrote: “If Christianity had been stopped in its growth by some deadly disease, the world would have been Mithraic”. Mithras is often depicted as Christ’s chief rival and is also often given very Christian traits in the collective imagination. For example, it is often assumed that the date of Christmas on 25 December was taken from a Mithraic festival celebrated on the winter solstice. But this is a misconception because the Mithras cult was never an official cult in Rome. The festival of the winter solstice is that of Sol Invictus, the sun god who was elevated to statehood by Emperor Aurelian in 274. It was this public, official and popular festival that the Church Fathers recycled by replacing it with the festival of Christmas. Mithras has nothing to do with it.

Source: Catalogue “The Mithras Mystery – immersion in a Roman cult”, Royal Museum of Mariemont (Belgium) – 2021