Michel Gybels for Time Travel Rome

The Costa Brava on the Mediterranean coast in Spanish Catalunia is best known for its seaside resorts and nightlife and attracts crowds of tourists every summer. Less well known, however, is that there are also interesting archaeological sites and museums to visit there. In the region of Girona, this includes the Greco-Roman site and museum of Ampurias, located near l’Escala on the coast.

A Resort rich in History

Ampurias (in Catalan Empúries; from Ancient Greek Ἐμπόριον, meaning “market”, “port of trade”; in Latin Emporiae); was a Greek and Roman city located in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula, in the Girona region of Alt Empordà. It was founded in 575 BC by settlers from Phocis as a trading enclave in the western Mediterranean. The Ampurias outlet to the sea was open to all. The reason was that the Iberians, ignorant of navigation, were happy to trade and wanted to buy foreign goods that the ships carried, and to sell the products of their harvests. The interest in trade made the Iberian city accessible to the Greeks. It was later occupied by the Romans, but the city was abandoned in the High Medieval Ages, except for the nucleus of Sant’Marti d’Ampurias which is still populated today. It was presented in 2002 as a candidate for Unesco Heritage World Status.

The archaeological sites of Ampurias are located on the Gulf of Rosas, in the municipality of l’Escala (Girona) and are some of the most important Greek remains in Spain. The area is made up of a sunken plain through which the rivers Ter and Fluvia flow. It is not a single nucleus but three distinct ones: Palaiápolis, Neapolis and the Roman city.

Palaiapolis (Greek παλαιάπολις, “ancient city”) is mentioned by Strabo as the foundation of the Phocians of Massalia (actual Marseille in France), who worshipped the goddess Artemis of Ephesus. This first colony was established on an island off the coast, which today would be Sant’Marti d’Ampurias.

The term Neapolis (Greek νεάπολις, “new city”) is the term commonly used by the Greeks for the growth area of a city, and was given in this case to designate the settlement located to the south of the Paliapolis, already inland. This settlement was born as a result of the demographic growth that the old city could not support.

View on the Greek part of the ancient city. By Enric – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

The Roman City is an ancient fortress (praesidium), located on a promontory further west of Neapolis. It is a rectangle of 750 x 350 metres enclosed by a wall that contains an urban system developed around several thistles and decumani.

Greek Emporion

In 575 BC, the last wave of colonisation Greek arrived on the peninsula, that of the Phocians, aimed at long-distance trade. The Phocians did not set up settlement colonies, but their aim was primarily commercial. The metropolis itself, Phocis, was built for this purpose.

Palaiapolis, the “ancient city“, was established as a mere island trading port to call at the mouth of the river Fluvia. With the arrival of the Greeks, the natives became producers of consumer goods which they exchanged with the Hellenes for more valuable goods such as wine. At first it depended on Massalia (actual Marseille in France), as can be seen in the large number of Massalian amphorae found from that period.

In 550 BC, according to Strabo, a second foundation was established, this one on the mainland, to the detriment of Palaiapolis, which underwent great urban development. Strabo’s words are recorded in his Geography:

“The Emporitans used to inhabit a small island off the coast which is now called Palaiapolis, but today they live on the mainland. Emporion is a double city, being divided by a wall, having before, as neighbours, some Indiketes (…). But in the course of time they were united into a single state, composed of barbarian and Greek laws, as is also the case in many other cities”.

Strabo, Geographia, III. 4, 8.

After the conquest of Phocaea by Cyrus II, Emperor of Persia in 546 BC, the Phocaeans fled to the new colony of Alalia in Corsica. However, their presence eventually annoyed the Carthaginians, who formed a coalition with the Etruscans to wipe them out. The Battle of Alalia took place in 535. The Phocians fled again, this time taking refuge in Massalia and Emporion. The population of the city was considerably increased by refugees.

The 5th century BC saw a period of great prosperity based mainly on Greek trade, especially with Athenian supplies. Political and commercial agreements were established with the indigenous population (who founded the city of Indika nearby). Due to its location on the trade route between Massalia and Tartessos, the city became a major economic and commercial centre as well as the largest Greek on the Iberian peninsula.

Remains of the Greek Agora. By Enric – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

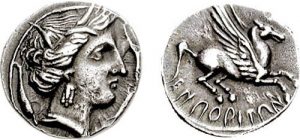

From the 4th century BC onwards the city grew considerably and became known as Emporion, Ἐμπόριον. There was still a lot of Greek trade with the peninsula and the first coins began to be minted, anepigraphic (without inscription) at first, and later with the legend EM. At the end of this century drachmes were issued with the type of the standing horse, according to the Punic model, and later with the characteristic Pegasus on the reverse and the head of Arethusa on the obverse.

Emporion. Circa 241-218 BC. AR Drachm. Head of Arethusa right; three dolphins around / Pegasos flying right. Source: cngcoins.com. Used by permission of CNG.

The period of splendour continues until the arrival of the Barcids. Competition creates a recession in the Emporitan economy. The Emporitans send an embassy to Rome asking for help. Rome conclude the Treaty of the Ebro with Ashdrubalte in 226 BC, according to which the Punics could not cross the river. With the Second Punic War, Ampurias became a loyal ally of Rome. In 218 BC, the Romans sent an army, which landed in Ampurias, with the mission of cutting off the supplies of Hannibal, who was ravaging Italy. This fact is quoted by Titus Livy:

“While these things were going on in Italy, Cn. Cornelius Scipio, sent to Hispania with a squadron and an army, sailed from the mouths of the Rhone and, rounding the Pyrenees mountains, landed at Ampurias. He landed his army there, and starting with the Lacetans, he subdued Rome along the whole coast as far as the Ebro, sometimes renewing alliances, sometimes establishing them.”

Titus Livy, Ab Urbe condita libri, XXI. 60, 1-3.

Ampurias under Roman Rule

The first Roman presence in Ampurias meant the construction of a stable Roman army camp, where the Roman city is today, although the existence of this camp did not mean the submission of the Greek city to the Republic, but rather that both were equal. This happened with the arrival in Hispania of the consul Marcus Portius Cato. After landing at Rosas, his army (estimated at between 52,000 and 70,000 men) headed for Ampurias. Titus Livy refers to this fact in describing the city:

“Ampurias consisted of two cities separated by a wall. One city was inhabited by Greeks from Phocis, like the Massaliotes, and the other by Hispanics. The Greek city, close to the sea, was surrounded by a wall of less than 400 paces. The Hispanic city, further from the coast, had a wall with a perimeter of 3,000 paces (…) The part of the wall facing the land, well fortified, had only one gate guarded by a magistrate in turn. At night a third of the citizens stood guard on the ramparts (…)”.

Titus Livy, Ab urbe condita, XXXIV, 9.

Around 100 BC, a new Roman city was built, which coexisted on an equal footing with the old Phocaean colony. Over time, the presence of Rome so influenced the small Greek nucleus that the Greeks themselves became Romanised, until during the reign of Augustus were granted Roman citizenship, which meant that the Greek and Roman nuclei were physically united.

We also know, thanks to some passages in Strabo and Titus Livy, about an indigenous Indika nucleus being part of the complex. They explain that the Greco-Roman community and the indigenous community lived separated by a wall.

The city maintained its institutions until the civil war between Pompey and Julius Caesar when the Pompeian party won the city, which meant, after Caesar’s victory, the annulment of its independence and the establishment of a colony of veterans alongside it.

Remains of the Roman Baths. Photo by Michel Gybels. Used by the permission of the author.

From the 1st century AD, after the total conquest of Iberia by Rome, Ampurias fell into decline, overshadowed by the power of Tarraco and Barsina (actual Tarragona and Barcelona) which became the capital, caused the ancient Roman cities of Republican origin to enter a process of decadence. At the end of the 1st century AD, Ampurias began to be abandoned.

Ampurias during Late Antiquity

In the 3rd century AD the population moved to the ancient Palaiapolis, which was better fortified. The Greek town became a cemetery, while the Roman town survived as a settlement until the Norman invasion in the 9th century. The continued importance of this small town was demonstrated by the fact that, after the reconquest of northern Catalonia by Charlemagne in 785, Ampurias was the capital of the Carolingian county of the same name, a condition that the old town maintained until the progressive transfer of the counts in the 11th century to the nearby town of Castellón d’Ampuries.This move began as a result of the warning that the destruction to which Ampurias was subjected in the year 935 at the hands of an Arab squadron chartered and sent from Almería by Abderraman III was a threat to its security.

Paleochristian Basilica. By Enric – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Archaeological Research

- Ripoll’s leadership (1965-1981)

From 1965 onwards, prehistorian Eduardo Ripoll (between 1965 and 1981), a student of Almagro’s, took over the direction of the site. From 1961-1981, he carried out stratigraphic excavations in the area of the forum and surrounding areas. Excavations were carried out outside the walls in order to find the indigenous indiketa settlement. The Greek city was not touched and, as for the Roman city, only a Roman military installation from the second quarter of the 2nd century BC was found.

- Reinterpretation of the sanctuaries and excavation in the forum (1990-2018)

From 1981 until recently, the director of the excavation has been Enric Sanmartí. Over the last two decades, thanks to the increase in human and economic resources, the information on the Roman city and the Neapolis has increased considerably, and in the latter case we have been able to learn much of the evolution of the site since the 5th century BC. Archaeological research at the site, which is one of the sites of the Archaeological Museum of Catalunya, is currently being carried out by a team made up of Pere Castanyer, Marta Santos, Quim Tremoleda and Xavier Aquilué.

Ancient water filtration pipes at Ampurias. Photo by Michel Gybels. Used by the permission of the author.

- The Palaiápolis

The island where Palaiápolis was located is nowadays joined to the mainland. On this island is the medieval village of Sant Marti d’Ampuries, while the part that was formerly the port and was buried by sediment is covered with vegetable gardens. This area has hardly been excavated because it has been inhabited since ancient times. It seems that after the foundation of Neapolis, the Palaiapolis was used as an acropolis (fortress and temple). Strabo spoke of a temple dedicated to Artemis located on this island.

- The Neapolis

In this section we will comment on the most representative buildings of the Neapolis, which was apparently founded in 550 B.C. It should be noted that almost everything that can be seen with the naked eye corresponds to the Republican and Imperial periods, and even to the beginning of the early Middle Ages. Therefore, what is strictly Greek, both from the Archaic and Classical periods and from the Hellenistic period, is found in the subsoil and is only visible in certain excavations carried out before 1939, and in the areas excavated from the 1980s onwards, especially in the southern part of the city.

- Walls and defensive constructions

The Neapolis consisted of a walled enclosure forming a highly irregular rectangle measuring 200 m by 130 m, with the port to the north. The south of the Neapolis is enclosed by a cyclopean wall built in the second half of the 2nd century BC. A large part of the limestone blocks that make up the wall come from an earlier Greek wall dating from the 4th century BC, the remains of which have been found. The remains of this wall have been found some 25 metres inland from the city. When the wall was moved, its stones were used, as mentioned above, to build the outer wall, while what was left was buried under a large amount of earth that raised the level of the city considerably.

Ampurias Walls and entrance into the Greek part of the city. Photo by Michel Gybels. Used by the permission of the author.

The wall was moved in the 2nd century BC, probably to make room for a new temple complex because of the need to gain space to build a complex of new temples. The new wall, dating from the 2nd century BC, is flanked by two quadrangular towers. The new 2nd-century BC wall is flanked by two quadrangular towers and the southwestern corner was protected by an important bastion. Although the existence of a wall dating from the 4th century BC and another from the 2nd century BC have been mentioned, it is not known whether the wall was built in the 4th century BC or in the 2nd century BC. Several archaeological excavations have revealed the existence of a parapet or Proteichism from the second half of the 3rd century BC, which is now located in the south-west corner of the city, below the Serapis enclosure, which would have prevented the war machine from coming closer to the wall than was desirable.

As for the wall that enclosed the Neapolis to the west, the existence of a large watchtower has been documented, which has been dated to the 5th century BC; this fortification and a tower from the same century found in the southern part of the city must have formed part of a defensive complex prior to the construction of the wall in the 4th century BC. This fortification and the tower from the same century found in the southern part of the city must have formed part of a defensive complex prior to the construction of the city wall in the 4th century BC. Finally, the western wall separated Neapolis from the Iberian city of Indika.

- The Asclepius enclosure

In the space gained by the extension of the city wall to the south of the city in the 2nd century BC, various religious buildings were built. With the extension of the wall, the original Asclepius enclosure, dating from the 4th century BC, was completely altered and was now built within the city walls. The Asklepieion was completely modified and now stands within the city walls. It was a therapeutic and religious centre dedicated to the god of medicine, Asclepius.

Statue of Asclepius at Ampurias. Photo by Michel Gybels. Used by the permission of the author.

The enclosure seems to have consisted of the three temples to the west of the complex, together with some cisterns, a well, and finally a porticoed building or αβατον (abaton), a building where the sick experienced the sacred sleep from which the priests established the therapeutic treatment to be followed. As for the cisterns, they were the place where the water necessary to carry out the purification rites to which the sick person had to submit was stored, and the open well perhaps housed the snakes consecrated to the god.

- The Serapis enclosure

In the middle of the 2nd century BC the Serapis enclosure was built, at the same time as the outer city wall was being built and the Greek wall of the 4th century was demolished. It was decided to build a porticoed square in Ampurias in the space gained by moving the wall. Later, probably in the first half of the 1st century BC, it underwent major alterations, the square underwent a major transformation when a Doric tetrastyle temple with lateral stairways was built in the western part of the square, probably dedicated to the divinity of Serapis. The existence of this enclosure to Serapis presupposes the importance that the cults from the eastern Mediterranean had in Ampurias in the Hellenistic and Republican periods, probably due to the effect that the arrival of merchants and traders from the East had on the city, who took advantage of the existence of a port city, open to the outside world, to establish themselves there and transform it in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC into a commercial and cultural emporium of great influence.

Serapeion at Empurias. By LeZibou – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Civic buildings

Excavations have brought to light a Hellenistic urban centre consisting of an agora, a stoa and a market, buildings located in the central area of the Neapolis, where the two main roads of the city meet. These buildings were constructed in the mid-2nd century BC. To do so, part of the existing neighbourhood in that area had to be destroyed. The buildings together occupy half a hectare and are situated around an arcaded square measuring 52 x 40 metres.

The Roman City

The Roman city has not yet been fully studied (only 20 % of the excavations have been completed). The construction of the Roman city took place around 100 BC, with the construction of a new city with an orthogonal urban layout, which during the 1st century and until the time of Augustus, remained independent of the Greek city, until during the reign of Augustus, after first the natives and then the Greeks obtained Roman citizenship, they merged into a single municipality known from then on as emporiae, and made up of people of Italic, Iberian and Greek lineage. It should be noted that the Roman city roughly occupies a rectangle measuring approximately 700 x 300 metres.

- Domestic architecture

Our knowledge of the Roman houses in the Roman city is limited to three large domus, located on the eastern side of the city, above the port. They are large mansions following the Italic pattern of the atrium house complete with peristyle and hortus. Like the city itself, they date back to the Republican period and were built when the first inhabitants received their plots of land on which to build their dwellings, which, especially in the Imperial period, underwent major extensions. The houses have numerous outbuildings, gardens and are decorated with black-and-white mosaics and wall paintings. A mosaic depicting the sacrifice of Iphigenia is preserved in good condition in one of them.

Roman residential area – remains of the mosaic floors. Photo by Michel Gybels. Used by the permission of the author.

- City wall

Of the Roman wall, built at the end of the 2nd century BC, the best-preserved section is that of the southern enclosure, where we find a straight wall, without towers, consisting of two sections: the inner section, made of polygonal limestone ashlars, and the upper section of opus caementicium, a concrete made of lime, sand and stone. The gate located in this section of the wall, whose lintel still shows the ruts of the wagons, is particularly noteworthy. The function of this wall was not defensive, but to delimit the city enclosure and differentiate it from the surrounding agricultural territory, the ager. The reasons for this are its low height, about 3 metres, the absence of towers, and unfortified entrances.

Roman Wall. Link: wikimedia.commons. CC BY 2.0.

- The forum

It consisted of a public square around which were distributed the main buildings of the city, whose functions were religious, administrative and commercial. One of the most important buildings was a large temple, built in the Republican period, with a south-facing façade. The temple was prostyle and tetrastyle, and stood on a podium which has now practically disappeared, and was dedicated to the Roman triad: Jupiter, Juno and Minerva.

The temple was surrounded by a large portico with three naves, in the shape of an inverted U, raised on a cryptoportico. This complex was accompanied by thirteen tabernae open to the north. Also to the east was a civil basilica and a curia, buildings constructed during the reign of EmperorAugustus. Finally, it should be noted that with the construction of the forum, the importance of the agora square in the Greek city began to decline, as religious and administrative functions were transferred to this area.

- The amphitheatre and the palaestra

An amphitheatre and a palaestra were built outside the city enclosure at the end of the 1st century AD. The amphitheatre is a building constructed of low-quality materials, and its stands were almost certainly made of wood. As for the dimensions of the building, its axes measure 93 x 44 metres, and it is surrounded by a portico. To this day it is the only public building used for performances, as it has not yet been possible to document the existence of a theatre.

Remains of the ancient amphitheater. By Enric – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

- Necropolis

The necropolis of Ampurias lasted more than a thousand years, from the 7th century BC to the Middle Ages. Many of its tombs were plundered in antiquity. The historian Almagro produced two volumes that contain all the data on most of the cemeteries in the area. There are four types: Greco-Indigenous, Late Republican, High-Imperial and Low-Imperial.

Late Republican (2nd century BC – 1st century BC)

We find an ancient group that will continue to use the ancient inhuming/incinerating necropolises, possibly the Greeks and indigenous people of the Neapolis. Another group will be predominantly incinerators and will have their necropolis on a hill where an ancient indigenous settlement, Paralli, was previously located. The oldest documented necropolis is the one on the northern slope of the neighbouring Les Corts hill, located to the southwest of the city. This necropolis functioned mainly during the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, where we find small square-shaped tumuli built with ashlars in the centre of which are the remains of cremation.

High-Imperial (1st c. BC – 2nd c. AD)

There is no clear record of burials from the second quarter of the 1st century BC until the time of Augustus, some 35 years. From then onwards, burials (only cremations, no inhumations) are found on the hillside on which the Roman city is built. Burial began to be imposed in the 2nd century.

Low-Imperial (3rd c. AD – 6th c. AD)

It is not easy to talk about this period, nor is it easy to give precise chronologies due to the lack of grave goods in the tombs. The whole area of the ancient Greek city was full of burials, perhaps related to the cult of the early Christian basilica (or Cella Memoria, a chapel with relics of a martyr) located there. Burials also continue in many of the ancient necropolises from earlier times (such as Bonjoan, in use for a thousand years since the first Greek colonisation) and some completely new ones. Perhaps these were related to the Roman villae or country houses located near them. The funerary monument of El Castellet and the tombs around it are particularly noteworthy.

Remains of Necropolis at Ampurias. Photo by Michel Gybels. Used by the permission of the author.

The museum

The headquarters of the Archaeology Museum of Catalonia in Empúries (MAC-Empúries) aims to offer visitors an exciting and enriching experience, in direct contact with the archaeological remains. The visit to the Greek city and the Roman city is complemented by a visit to the museum, where you can see objects representative of the history of the site, discovered during the more than 100 years of excavations in Empúries.

Ancient ceramics found in the area of the Greek necropolis. Photo by Michel Gybels. Used by the permission of the author.

Statue of Asclepius in the museum of Ampurias. Photo by Michel Gybels. Used by the permission of the author.

Ampurias on TimeTravelRome

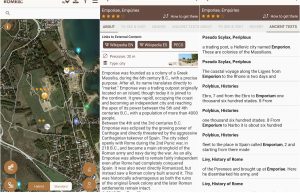

The site of Ampurias is well featured in the TimeTravelRome mobile App: a description of the site is provided, as well as the description of main monuments. The museum and monuments are located on the map. Screenshots from the App:

Source: Xavier Aquilué e.a., Empúries (2000)