“Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale her infinite variety. Other women cloy the appetites they feed: but she makes hungry where most she satisfies.”

– Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare

Meeting on the Kydnos

Cleopatra was not deeply involved in the civil wars that immediately followed the assassination of Caesar, though she stayed in steadfast support of her former lover – whether from loyalty or a shrewd evaluation of the likely winners. Both Cassius, one of Caesar’s assassins, and Dolabella, a leader of the party loyal to Caesar, petitioned Cleopatra for support. Although she committed four legions to Dolabella, they were captured by Cassius and later Serapion, the governor of Cyprus appointed by Cleopatra, defected to the conspirators, leaving Cleopatra’s loyalties in doubt.

Cleopatra Gate in Tarsus. By CeeGee – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

In order to reaffirm her loyalties, Cleopatra set sail for Greece with a large, well-provisioned fleet, intending to aid Octavian and Antony in the war against Brutus and Cassius. Unfortunately, she ran into heavy weather off the coast of Libya that badly damaged her fleet and she was forced to limp back to Alexandria, herself suffering from illness. By the time she had recovered and gotten her fleet refitted, Octavian and Antony had triumphed over the conspirators at the Battle of Philippi and the war was won.

Ancient road in Tarsus. By CeeGee – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Octavian and Antony effectively split administration of the Roman provinces between the two of them, with Octavian controlling the western half and Antony the eastern. Antony set up headquarters in Tarsus, and summoned Cleopatra to pay him audience there. The queen initially refused, but eventually agreed to visit, and sailed from Alexandria and up the Kydnos River on lavishly decorated ships.

First Impressions

Cleopatra had every intention of making an unforgettable impression as she sailed up the river “in a barge with gilded poop, its sails spread purple, its rowers urging it on with silver oars to the sound of the flute blended with pipes and lutes. She herself reclined beneath a canopy spangled with gold, adorned like Venus in a painting, while boys like Loves in paintings stood on either side and fanned her. Likewise also the fairest of her serving-maidens, attired like Nereïds and Graces, were stationed, some at the rudder-sweeps, and others at the reefing-ropes. Wondrous odours from countless incense-offerings diffused themselves along the river-banks.”

The Disembarkation of Cleopatra at Tarsus by Claude Lorrain (1642). Public Domain.

The inhabitants of Tarsus whispered that Venus had arrived to join in revels with Bacchus, and so it proved. Cleopatra and her courtiers entertained Antony with opulent luxury aboard their ships, which were adorned in a myriad of draping lights. The next day, Antony gave a feast in return, but it paled in comparison with Cleopatra’s preparations the night before. Nevertheless, Cleopatra made light of the discrepancy, and charmed Antony with her ready intelligence and easy manner. Plutarch gave perhaps the most complete, yet succinct description of her abilities:

“Her beauty, as we are told, was in itself not altogether incomparable, nor such as to strike those who saw her; but converse with her had an irresistible charm, and her presence, combined with the persuasiveness of her discourse and the character which was somehow diffused about her behaviour towards others, had something stimulating about it. There was sweetness also in the tones of her voice; and her tongue, like an instrument of many strings, she could readily turn to whatever language she pleased.”

A Luxurious Affair

Antony was suitably enthralled by the charismatic queen, and granted her requests to execute both her own sister, Arsinoe IV, and the traitorous governor of Cyprus. She left Tarsus with an invitation to Antony to join her in Egypt, which he swiftly did. There the two enjoyed a luxurious affair, even creating their own association which they called “The Inimitable Livers,” and every day they feasted one another in costly fashion. The affair also produced offspring, a twin brother and sister whom Cleopatra named Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene. Unlike Caesar, Antony openly acknowledged the two as his own.

Mark Antony & Cleopatra. Circa 36-34 BC. AR Tetradrachm. Obv: diademed bust of Cleopatra right, wearing earring, necklace, and embroidered dress. Rev: bare head of Antony right. Used by permission of www.cngcoins.com

Octavian had little difficulty turning Antony’s dalliances in Egypt to his advantage back in Italy, where hostility was rising between the two former allies. Antony’s brother and his wife, Fulvia, even staged a failed coup against Octavian, which came to be known as the Perusine War. Though Fulvia escaped death in the uprising, she died soon after while exiled in Greece. Her death temporarily reconciled Antony and Octavian, and Octavian gave Antony his sister, Octavia, in marriage. Yet Antony soon enough left his new wife with his children by Fulvia and returned to Cleopatra in the east.

Egypt, The Egyptian Museum, children of Cleopatra and Marc Antony, Cleopatra Selene, Caesarion, limestone. Source: www.historytoday.com

When the rift between the two men began to grow once again, Octavian easily swayed public opinion against Antony by pointing to the latter’s obsession with Egypt and betrayal of his good, loyal Roman wife. The situation finally exploded in early 32 B.C., when Cleopatra convinced Antony to send Octavia an official declaration of divorce. Octavian used this as a justification to seize Antony’s will and read it aloud, revealing to the fury of the Romans present that Antony intended to make Alexandria the capital of the Roman Republic. Octavian officially declared war on Cleopatra, not on Antony, though he knew that the latter would join Cleopatra in the fight.

Defeat and Death

The war was relatively short-lived. Antony and Cleopatra had lost numerous allies, and though their ships outnumbered Octavian’s, their crews were far less experienced and skilled. They met Octavian’s fleet, under the command of Marcus Agrippa, for battle outside their headquarters at Actium, and eventually suffered a major defeat. Both Antony and Cleopatra escaped from Actium, fleeing back to Egypt where they landed at Paraitonion and drifted apart. Antony vainly hoped to rally allies to his cause, and Cleopatra planned an escape to India by sea, a journey known to the Ptolemaic kings for generations. Her hopes were dashed, however, when Malichus I, King of Nabatea, burned the ships she had staged for the escape.

Relief commemorating the Battle of Actium discovered in Avellino. Carrara marble, Tiberian period. By Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Antony and Cleopatra waited anxiously in Alexandria for the arrival of Octavian, who received the surrender of Antony’s fleet and cavalry in early August of 30 B.C. Cleopatra hid in her tomb and sent a message to Antony that she had committed suicide. In despair and grief, he stabbed himself in the stomach. A stomach wound does not kill quickly, however, and Antony was brought, badly wounded, to the tomb, where Cleopatra lifted him with ropes, smeared with blood and struggling against overwhelming pain, over the great barrier at the entrance of the tomb. He died in her arms.

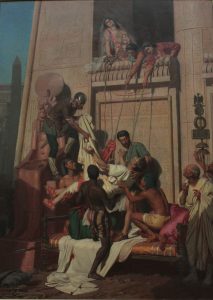

Dying Antony brought to Cleopatra. Eugène-Ernest Hillemacher. Public Domain.

Cleopatra attempted to negotiate with Octavian, first diplomatically and then romantically, but Octavian rejected her advances. Finally, learning that she was to be moved to Rome and refusing to be led in a Roman triumph, Cleopatra took her own life. Famously, she is said to have died by allowing a venomous snake, an asp, to bite her. Octavian allowed Cleopatra and Antony to be buried together, but their tomb has yet to be found.

What to See Here Now?

Tarsus:

There are several significant remains of antiquity to be seen in Tarsus, though the state of preservation varies with most in need of restoration and preservation. One of the most striking survivors from antiquity is the so-called “Cleopatra Gate” in the west of the city; according to legend this great arched gateway is the entrance into the city which was taken by Antony and Cleopatra. There is also an impressive bridge, dating to the Justinianic period (early 6th century), when the city was restored. It spans over the Berdan River and remains in good condition. The museums in Tarsus are rich in archaeological finds.

Tarsus, Cilicia, Turkey. By Carole Raddato. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Paraitonion:

Paraitonion is a large archeological area, but perhaps the most well-known historical attraction is the Temple of Ramesses II. Also of note are the ruins of a Ptolemaic Era anchorage site in the harbor, and an early Coptic chapel of the Roman Period, perhaps from the 1st century, with several inscribed caves.

Abu Simbel Temples of Ramesses II and Nefertari. Taken by Than217, Public Domain.

Sources: Sources: Plutarch, Life of Caesar; Cassius Dio, Roman History; Appian, Civil Wars; Caesar, African Wars; Suetonius, Life of Caesar

Header image: The Meeting of Antony and Cleopatra. By Lawrence Alma-Tadema – Sotheby's New York, 05 Mai 2011, lot 65, Public Domain.