To modern ears, the name Cleopatra refers to only one woman – the famed last Queen of Egypt who tragically chose the wrong lover and the wrong side in the Roman Civil Wars. However, this famous Cleopatra was actually known as Cleopatra VII, the last in a long line of kings and queens descended from the Macedonian general Ptolemy I Soter. The original Ptolemy had risen to kingship of Egypt during the chaotic wars that followed the death of Alexander the Great. A skilled general, powerful personality, and shrewd politician, he had founded one of the great Hellenistic Empires that directed the course of Mediterranean history between the Macedonian Empire and the rise of Rome.

Yet by the time of Cleopatra, the Ptolemaic Empire was not what it had been. Generations of kings living in luxury had weakened the ambitious of the kings and queens, family infighting and dynastic squabbles frequent, and the empire almost bankrupt. Into this situation stepped Cleopatra, a ruler more reflective of the first Ptolemaic kings – intelligent, quick, opportunistic, and ruthless when necessary – a product of the philosophic haven that was ancient Alexandria. Yet from the beginning of her reign, she was playing with a deck stacked against her.

Portrait coin of Cleopatra VII Thea Neotera. 51-30 BC. Æ Diobol – 80 Drachmai. Alexandreia mint. Used by permisson of CNG. www.cngcoins.com.

Ineffective King in a Failing Kingdom

Cleopatra was the second daughter of Ptolemy XII of Egypt. Her father had become king after a palace coup. As the illegitimate son of Ptolemy IX, he was the closest male heir. Yet by that time Egypt was already practically a weak client kingdom of Rome. Ptolemy XII did nothing to strengthen his kingdom. In fact, he was far more interested in feasting and music than in business or politics. His love of flute playing in festivals earned him the disdainful moniker Auletes, which meant flute player. Fully aware of his lack of clout as a ruler, Auletes sought desperately for the support of Rome to maintain his power.

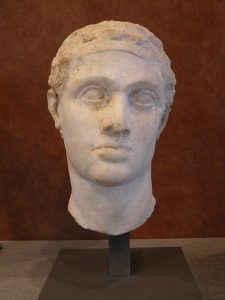

Ptolemy XII, called “Auletes” (the “Flute Player”), 1st century BC, discovered in Egypt, Louvre Museum. By Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0.

In 63 B.C., he sent a large monetary gift along with an invitation to Pompey. Although Pompey accepted the money, he declined to visit, and Auletes followed up by traveling to Rome personally to present large sums to both Pompey and Caesar, and was acknowledged as a formal ally and friend of Rome. However, his massive gifts bankrupted Egypt, and he imposed heavy taxes on the citizens to compensate. Unrest grew until it finally exploded into open rebellion. The Egyptian people deposed Auletes and placed his eldest daughter, Berenice, on the throne.

Auletes fled to Rome along with a teenaged Cleopatra. After some initial struggles with Roman Senators opposing his bid, he finally bribed the Roman general Aulus Gabinus to invade Egypt in 55 B.C. Upon taking the palace, Auletes immediately executed his daughter Berenice and her supporters, and reigned for the next three years under considerable influence from Rome.

Challenging Circumstances for the New Queen

Yet Auletes was slowly weakening, and early in 52 B.C., he became so ill that he named Cleopatra co-regent. Having grown up in the court of her father in Alexandria, Cleopatra had been educated by some of the top philosophers of the age. In her later years, she was said to have frequently gone to the Museum of Alexandria to converse with the scholars there, and her visits likely began even earlier. By the time she became co-regent at sixteen years old she was already an intelligent, polished, and diplomatic stateswoman. She had traveled the world and experienced Rome firsthand. Her first year of co-rule gave her further administrative experience. When her father died in 51 B.C., his will named Cleopatra and her ten year old brother, Ptolemy XIII, as co-rulers. In strong Ptolemaic tradition, Cleopatra promptly married her little brother, but their cooperation was short-lived.

Sphinxes at the Serapeum of Alexandria. By Institute for the Study of the Ancient World – CC BY 2.0.

They inherited a kingdom wracked with problems. Famine devastated the land, and the soldiers left by Gabinius were becoming outlaws. On top of everything, they now owed the Roman Republic the debts incurred by their father, totaling some 17.5 million drachmas. Calculating an exact exchange with modern currency is difficult, but one drachma was about a days’ worth of wages for a skilled laborer. The full debt amounted to something like 210 billion US dollars or 178 billion Euros today. Soon, conflict arose between the two siblings, exacerbated by the court advisors, who rightly expected they could exercise more power over the younger Ptolemy than his smart, headstrong, older sister. Eventually Cleopatra was forced to flee to Syria with her younger sister, Arsinoe. There they planned to raise an army to reclaim the throne for Cleopatra.

An Opportunity Seized

Yet at the same time, civil strife in Rome was soon to provide Cleopatra with the opportunity that she needed. Tensions between Pompey and Caesar had erupted into civil war, and eventually Pompey’s forces suffered a crushing defeat at Pharsalus. Pompey himself fled to Egypt, expecting a warm welcome on the strength of his former allegiance with Auletes. Yet the young Ptolemy thought it better to play to the winning side. He instructed his men to meet Pompey’s ships and welcome him, inviting him to come to shore in a small skiff to meet with the king. While still halfway between the ships and the shore, the men in the skiff turned on Pompey and stabbed him to death.

Portrait coin (denarius) of Pompey the Great. Struck by Sextus Pompey. 37/6 BC, Sicily. Used by permisson of CNG. www.cngcoins.com.

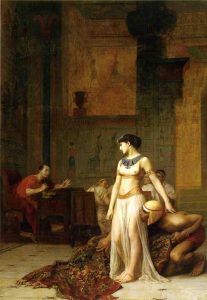

When Caesar arrived in Egypt in pursuit and came to the court of Ptolemy, the officials proudly offered him Pompey’s head, eagerly expecting high honors and rewards – but they fundamentally misunderstood Caesar. He turned in horror from the head and refused to even look at it. He did accept the signet ring of Pompey, also presented to him, but far from reveling in his triumph, he wept bitterly over it, and ordered his soldiers to execute the murderers. With her brother thus already on shaky ground with Caesar, Cleopatra saw her chance. Determined to meet with him, she had her friend Apollodorus carry her, concealed within a sack, into Caesar’s quarters, where she presented herself to the famous Roman to plead for his support.

Cleopatra and Caesar by Jean-Léon Gérôme – Public Domain.

Sources: Plutarch, Life of Caesar; Cassius Dio, Roman History; Appian, Civil Wars; Strabo, Geography

Alexandria: What to See Here Now ?

Though the capital of Hellenistic Egypt and equally crucial to Rome’s history, modern Alexandria offers relatively little in the way of ancient Roman artifacts compared to its importance. However, there are specific sites around the modern city with ruins worth visiting.

The Chatby (or Shatby) Necropolis in Alexandria is said to be the oldest Hellenistic necropolis in the city, with Egyptian, Hellenistic Greek and Roman influences. Much of the necropolis is visible at ground level, and many artefacts from the site are preserved at the Alexandria National Museum nearby.

Chatby necropolis in Alexandria. By Nikola Smolenski – Own work. CC BY-SA 3.0.

The necropolis in Alexandria now referred to as the Kom El Shoqafa Catacombs included a mixture of Roman, Greek and Egyptian features as well as the bones of Christians martyred during the reign of the emperor Caracalla. Much of the necropolis remains intact underground, including decorations and a circular staircase that was used to carry the deceased below the surface.

Exhibition area, Kom el-Shuqafa, Alexandria, Egypt. By Roland Unger, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Entrance of the principal tomb chamber. By Clemens Schmillen – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Kom el-Dikka, a suburb of Alexandria, is the site of a number of structures dating back to the Roman period including a small theatre, a substantial villa, and a modest bath complex. The theatre is fairly intact, with a number of columns and much of the stone seating still in place.

Roman Amphitheater of Alexandria. By ASaber91 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

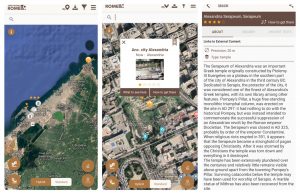

The Serapeum of Alexandria was an important Greek temple originally constructed in the third century B.C. Relatively little remains visible above ground, but surviving catacombs below the temple may have been used for worship of Serapis. A marble statue of Mithras was also recovered from the site. Pompey’s Pillar, a huge free-standing monolithic triumphal column nearby, was erected on the site in AD 297 by the Emperor to commemorate the successful suppression of an Alexandrian revolt.

The remains of the ancient site of the Temple complex of Sarapis at Alexandria. By Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. CC BY 2.0.

Serapeum of Alexandria. So called “Pompey’s Pillar”. By Hatem Moushir – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

Alexandria on TimeTravelRome App:

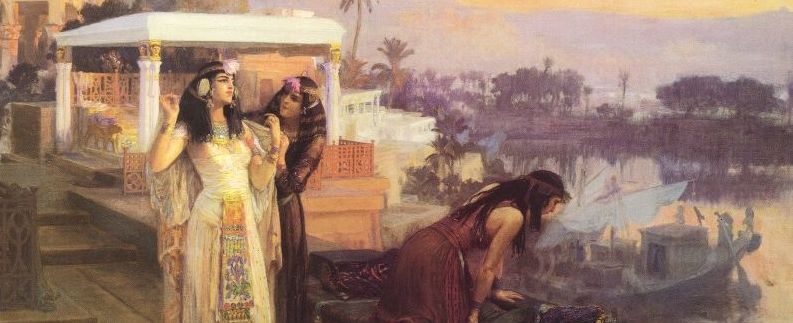

Source of the features image: “Cleopatra on the Terraces of Philae” by Frederick Arthur Bridgman – Public Domain.