Author: Marian Vermeulen

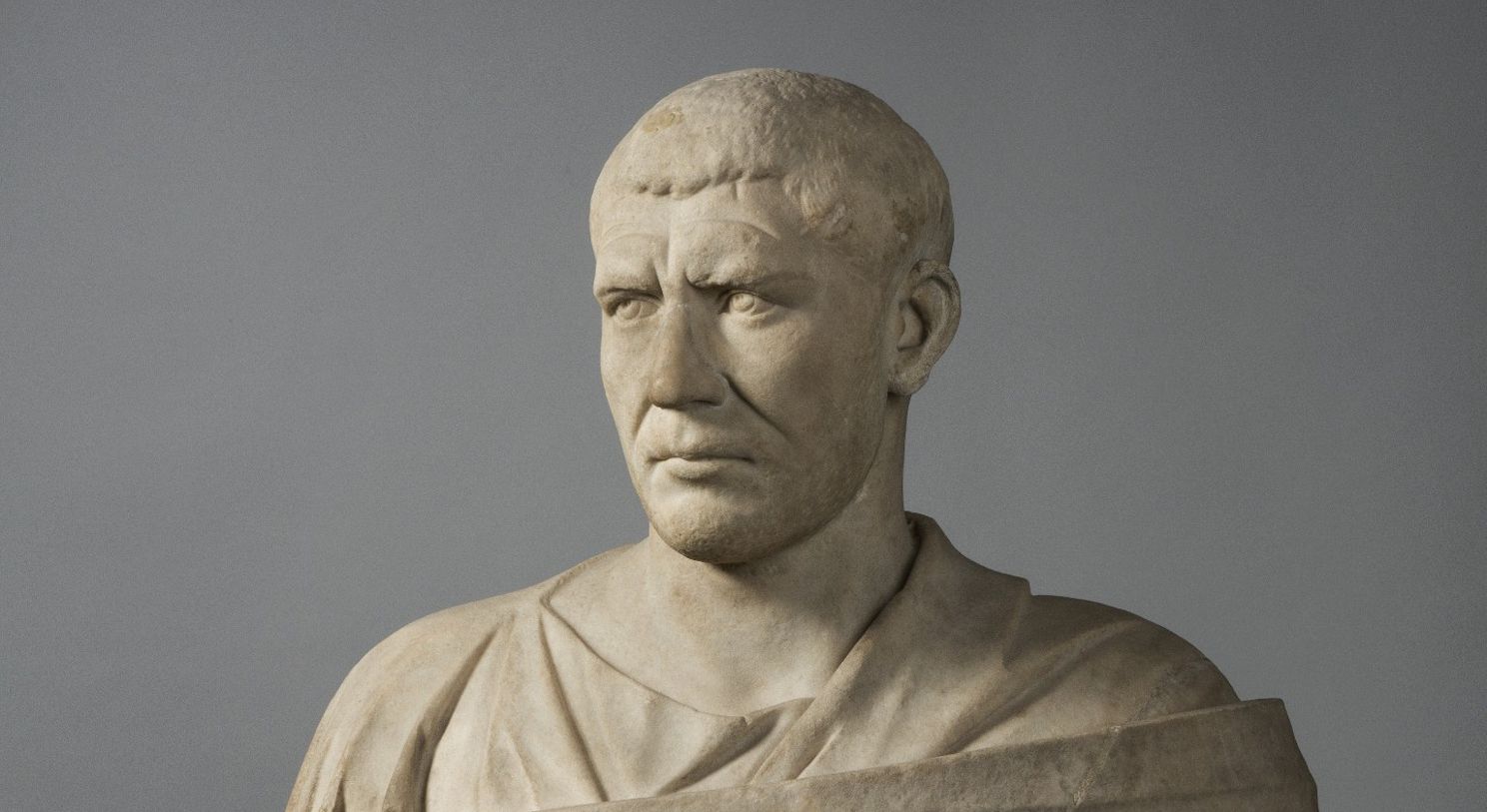

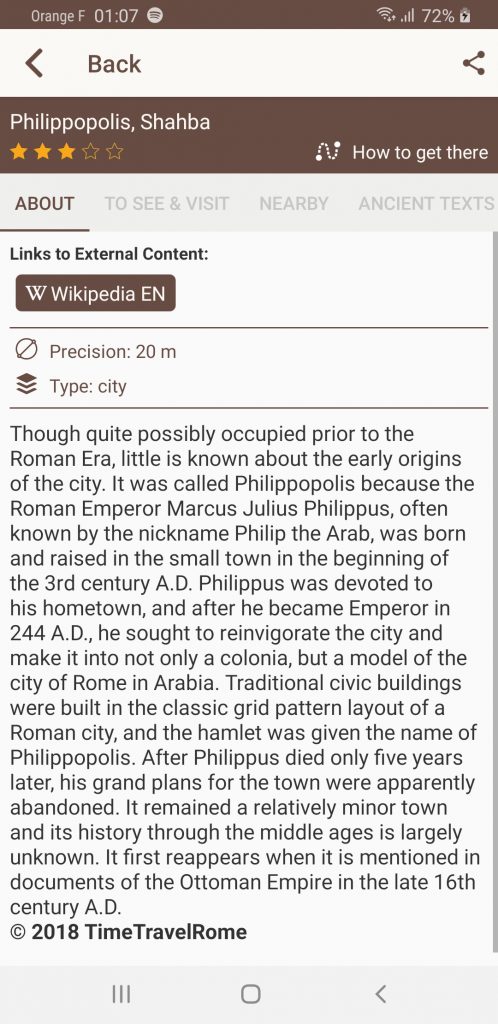

Marcus Julius Philippus, commonly referred to as Philip the Arab, is an enigmatic figure of Roman imperial history. For all the major events of his life there are two different explanations of the motives behind them and various versions claiming to be the true story. His early life remains almost entirely a mystery. His father, Julius Marinus, was a local official of Arab background, possibly important but possibly not. Some later ancient historians even suggest that he came from the most entirely humble of origins, or that his father lead a band of brigands. All that is known for certain is that he was born in what is now modern Shahba, Syria, a town that he would invest no little time and money into expanding and improving, renamed Philippopolis in his honor.

Praetorian Prefect

Coming from less than stellar credentials of nobility, one can assume that Philip and his brother Gaius Julius Priscus were competent individuals, as they advanced militarily and politically despite little in the way of familial advantage. Indeed Priscus became a very high official to the thirteen year old emperor, Gordian III. In 243 A.D., as Gordian campaigned against Shapur I of Persia, his Praetorian prefect, Timesitheus, became ill and eventually died. The Historia Augusta blames the death on Philip, relating that Timesitheus was suffering from an illness that caused diarrhea. The physicians concocted a medicine to help, but Philip intercepted it and switched it with something that caused the diarrhea to worsen instead. Dehydrated and dreadfully ill, Timesitheus eventually died.

Priscus immediately recommended his brother for the vacant position, and Philip became Praetorian prefect. He and Priscus essentially planned to act as regents for the young emperor. Yet Gordian III did not long survive either, and here the sources are again in disagreement. While several historians, including one Persian, claim that Gordian died in battle, others are equally convinced that Philip was involved in arranging for the emperor’s death.

Conspiring for the Throne

According to this tale, Philip diverted the supply ships and then instituted heavy rations on the soldiers under his command, under the pretense that the order had come from Gordian. As hunger overtook them, they became more desperate and frustrated. Philip began to spread the idea that Gordian was too young to be able to manage the empire, and that Rome needed a more able ruler. Eventually, weak with famine and enraged at their treatment, they revolted and named Philip emperor.

Gordian appeared before them to negotiate, thinking he could calm them down and regain his position through diplomacy, and it was not an insane belief. Gordian “was a light-hearted lad, handsome, winning, agreeable to everyone, merry in his life, eminent in letters; in nothing, indeed, save in his age was he unqualified for empire. Before Philip’s conspiracy he was loved by the people, the senate, and the soldiers as no prince had ever been before. … all the soldiers spoke of him as their son, he was called son by the entire senate, and all the people said Gordian was their darling.”

Yet in this case, there was nothing he could do to sway them. Despite asking for progressively less, and finally just pleading that Philip would make him a general and allow him to live, Philip ordered his death, and the soldiers carried him away and killed him. Yet despite this violent end, the Historia Augusta claims that Philip always treated the memory of Philip with respect. He may have been subversive, but he was also shrewd, and he was under no delusions regarding the love that Rome had held for Gordian. Therefore he left up all statues and portraits of the young emperor and requested Gordian’s deifications as well.

Tradition and Construction

Whether gained through devious murder or popular support following the death of an emperor with no heir, Philip was now the first citizen of Rome. He had learned the lessons of previous failed emperors, and was determined to placate the various powerful factions of the empire. Determined to return as quickly as possible to Rome to present himself before the Senate, he negotiated peace terms to end the conflict with Shapur of Persia. His decision was unpopular, however, for he gave up significant portions of previously conquered land and agreed to pay a large indemnity to Persia, 500,000 denarii. Still, he was able to declare himself victor in Persia, issue special coins in commemoration, and return speedily to Rome.

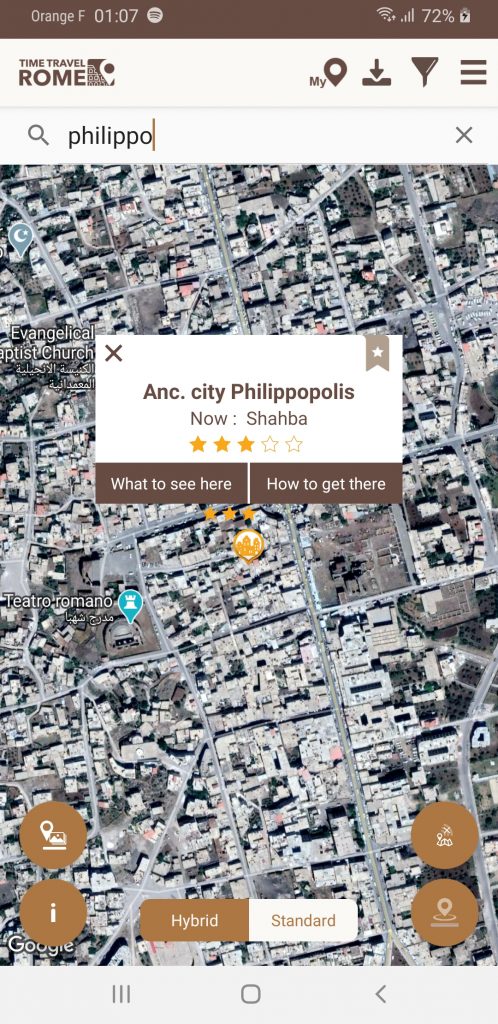

Philip successfully won the esteem of the Senate, after presenting himself humbly before the legislative body and promising to uphold traditional Roman laws, traditions, and virtues. One of his first endeavors was indeed very traditionally Roman: a public building project. Renaming his hometown Philippopolis, he poured money into a massive civic improvement program, at the same time commissioning statues of himself and his family to be displayed around the city. This largess, combined with the indemnity owed to the Persians and the massive monetary gift he had given to secure the loyalty of the army and the Praetorians left him hopelessly in debt.

The 1000th Anniversary of Rome

Philip’s only recourse to address his financial issues was to institute exorbitant taxes, losing the support of the people, and stop subsidies to the border units which helped insure peace on the furthest reaches of the empire. This mitigated his debts for a time, but left him to deal with several barbarian incursions along the Danube. Just when he might have achieved stability, he was once again forced to pay out huge sums of money that he didn’t have to celebrate a momentous occasion: the 1000 year anniversary of Rome itself.

The Roman Secular games corresponded with this event, and no expense was spared to hold a magnificent and extravagant festival. Philip issued commemorative coins, organized theatre productions, showcased literary works, and offered lavish games. Over 1,000 gladiators died in the days of the festival, as did huge numbers of animals, such as hippos, leopards, lions, giraffes, and even one very special victim, a rhinoceros. Unfortunately for Philip, the party was short-lived, more barbarian invasions coincided with rebellions by several Roman legions.

Farewell to Philip

Overwrought, Philip came before the Senate and offered to resign, but Gaius Messius Quintus Decius led the Senators in insisting that he maintain the position. Gratified, Philip appointed Decius as commander of the legions to quell the uprisings, but instantly upon Decius entering camp, the soldiers declared him emperor. Some of the histories suggest that Decius suspected this would be the case, and warned Philip not to give him the command, but Philip insisted. When Decius tried to refuse the acclamation, his soldiers forced him at sword point to accept, and he then sent a message to Philip begging him not to take action against him and promising that he would hand power back to Philip the second he entered Rome. Whether this was true or not, Philip distrusted the army that marched toward Rome, and he brought his own forces out to meet them near Verona.

Decius’s army easily crushed Philip’s, and Philip either died in the battle or was assassinated by his own soldiers shortly after, who hoped to gain favor with the emerging leader of Rome. Philip’s legacy is as confused as his life. Though many histories claim he took the throne through subterfuge and murder, there is no reference to the kind of widespread executions that often followed a planned coup. He enjoyed mutual respect with the Senate and even displayed an unusual tolerance towards Christians. Some later Christian authors even claim that Philip was actually the first Christian emperor, but no solid evidence supports this. He may have been a successful emperor had he not inherited an already unstable empire. As it was, his reign lasted only five years, and rule passed immediately out of his family line.

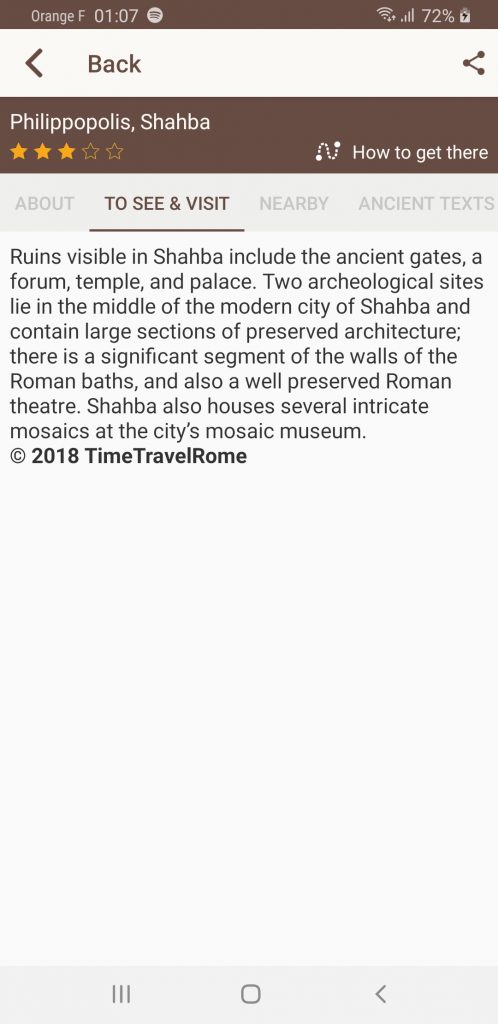

What to See in Philippopolis now ?

Ruins visible in Shahba include the ancient gates, a forum, temple, and palace. Two archeological sites lie in the middle of the modern city of Shahba and contain large sections of preserved architecture; there is a significant segment of the walls of the Roman baths, and also a well preserved Roman theatre. Shahba also houses several intricate mosaics at the city’s mosaic museum.

Philippopolis on Timetravelrome App:

Author: Marian Vermeulen for Timetravelrome

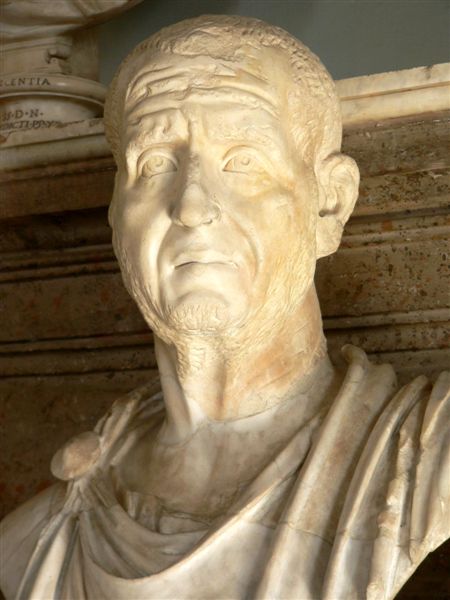

Header image: Portrait of the Emperor Philip the Arab, Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg.

Sources: Historia Augusta, The Three Gordians; Zosimus, New History; Zonarus, Alexander Severus to Diocletian; Sextus Aurelius Victor, Epitome De Caesaribus.