Author: Marian Vermeulen /

“He called up informers and incited accusers, invented false offences, killed innocent men, condemned all whoever came to trial, reduced the richest men to utter poverty and never sought money anywhere save in some other’s ruin, put many generals and many men of consular rank to death for no offence, carried others about in waggons without food and drink,and kept others in confinement, in short neglected nothing which he thought might prove effectual for cruelty.”

– Historia Augusta

First Barbarian Emperor of Rome

For centuries in the ancient world, kings were also expected to be front line warriors, leading their men into battle and earning their loyalty through their prowess on the battlefield. Yet the Romans embraced a more measured style of battlefield command, and while several emperors remained active generals, they were also more careful to insure their own safety for tactical reasons. Yet Maximinus Thrax, the first barbarian emperor of Rome and a giant of a man, returned to the warrior roots of the ancient world. An exceptional commander, he unfortunately soon found that an emperor requires political tact in additional to military talents.

Entering the Service

Maximinus was born around 173 A.D. close to the border of Thrace to common, barbarian parents. As a young man, barely even able to speak Latin, he presented himself before the Emperor Septimius Severus, requesting permission to compete in the military games that the emperor was holding to honor his youngest son, Geta. He was an exceptionally large man, the Historia Augusta even records one report that claims he as eight feet and six inches tall, and that his thumb was so large that he wore his wife-‘s bracelet on it instead of a ring. Impressed by Maximinus’s size and presence, Severus offered him several opponents, and after defeating sixteen, he was appointed to serve in the army.

Two days later, Severus again encountered Maximinus, and when the Thracian approached him, Severus began to circle with his horse, challenging Maximinus to race the animal. The emperor tired of riding before the Thracian tired of running, and then inquired if Maximinus now wished to wrestle. At his assent, Severus ordered the toughest men of the army to spar with Maximinus. He defeated seven at once, and was rewarded with silver pieces and a golden collar, as well as a permanent position in the emperor’s personal bodyguard. “In this fashion, then, he was made prominent and became famous among the soldiers, well-liked by the tribunes, and admired by his comrades. He could obtain from the Emperor whatever he wanted, and indeed Severus helped him to advancement in the service when he was still very young.”

General Becomes Emperor

Maximinus grew deeply loyal to Severus and to his family. After the death of the Emperor, Maximinus continued to serve honorably under Caracalla in command of commanding centuries, but was enraged by the assassination of his emperor. He hated Macrinus and refused to serve under him, instead withdrawing to a villa in Thrace. After the death of Macrinus, the teenaged cousin of Caracalla, Elagabalus, claimed the throne, aligning himself with the Severan Dynasty. Maximinus presented himself before Elagabalus, but the young emperor displayed his lack of character, and Maximinus resolved to retire again in disgust. However, some of Elagabalus’s friends convinced him to stay on, “lest this also be added to Elagabalus’s ill-fame, that the bravest man of his time — whom some called Hercules, others Achilles, and others Ajax — had been driven from his army.”

He therefore remained as a commander in the army, but he assiduously avoided the emperor. He was overjoyed at the death of Elagabalus and the succession of Alexander, another Severan cousin. He hurried to Rome to present himself to the new emperor and was warmly welcomed. He became Tribune of the Fourth Legion, and was given soldiers to train as he pleased. Eventually Alexander made Maximinus the commander of the entire Roman army, to his own destruction. While in Gaul, the army rose against the young emperor, possibly by instigation of Maximinus though the truth of his involvement is unknown, and executed him. Maximinus was declared emperor by the soldiers, the first non-Senator to receive the position, and the Senate had no option but to begrudgingly accept their decision.

Unpopular Rule

Maximinus began his reign with work on roads and infrastructures and a largely successful campaign into Germania. However, knowing he lacked the support of the Senate, he was utterly paranoid, and set about executing all of Alexander’s closest advisors and any that he feared might oppose him. Unsurprisingly, he quickly made enemies, and faced multiple attempts at a coup. An attempt on Maximinus’s life by one Magnus was quickly discovered and all those involved put to death. Another popular soldier by the name of Titus headed up a rebellion of Osroënian bowmen who had been devoted to Alexander and blamed Maximinus for his death. They had some success, but Titus was betrayed and killed by one of his own men.

Early in 238 A.D., a revolt broke out in Africa that declared the provincial governor and his son Gordian I and Gordian II, emperors of Rome. By this time, the Senate “could bear his barbarities no longer,” and they eagerly supported the claim of the Gordians and even declared Maximinus an enemy of the state, only to fall into despair when the governor of Numidia, who had a personal grudge against the Gordians, marched on Carthage and easily put down the rebellion. Gordian II was killed in the battle, and his father hanged himself in grief. Desperate now, the Senate doubled down against Maximinus, and threw their support behind Pupienus and Balbinus, two of their own members, as co-emperors. However, the Roman people favored the Gordians, and to settle any unrest, the Senate declared the former governor’s young grandson Gordian III, Caesar and heir.

Siege and Betrayal

238 A.D. became known as the year of the six emperors, another step in the steady decline of Roman power. Maximinus marched on Italy to reclaim his rule, but when he came to Aquileia, he found the city gates closed against him. The siege that followed was long and brutal. The townspeople defended with Sulphur and fire, destroying the siege engines, burning and blinding many of the soldiers. With the siege dragging on, the army began to run out of provisions, and Maximinus decided that the siege had remained unsuccessful due to cowardice. He executed his generals, enraging all of his soldiers. Finally, suffering the hardships of war and deprivation, they united in their hatred of him, killed him and his son while they slept in their tent, and mounted the heads on poles and displayed them to Aquileia before sending them on to be presented to the Senate.

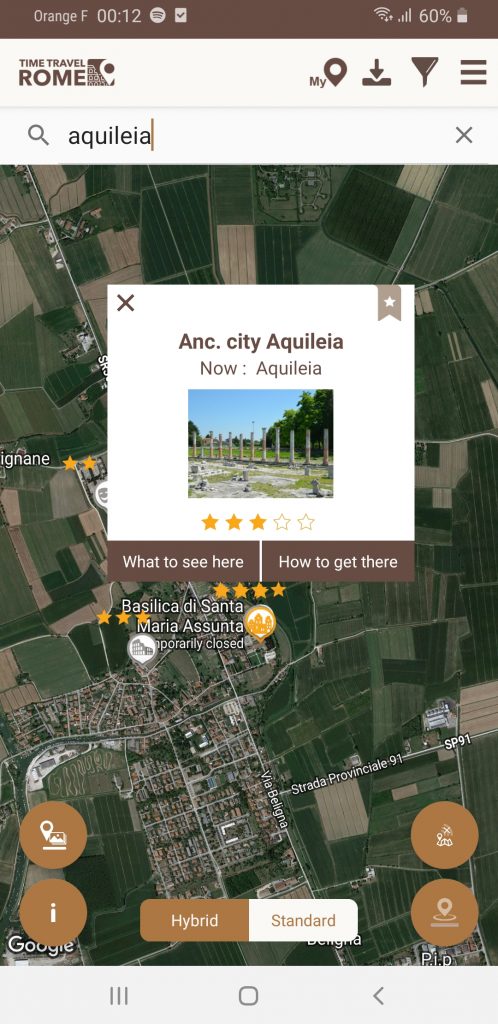

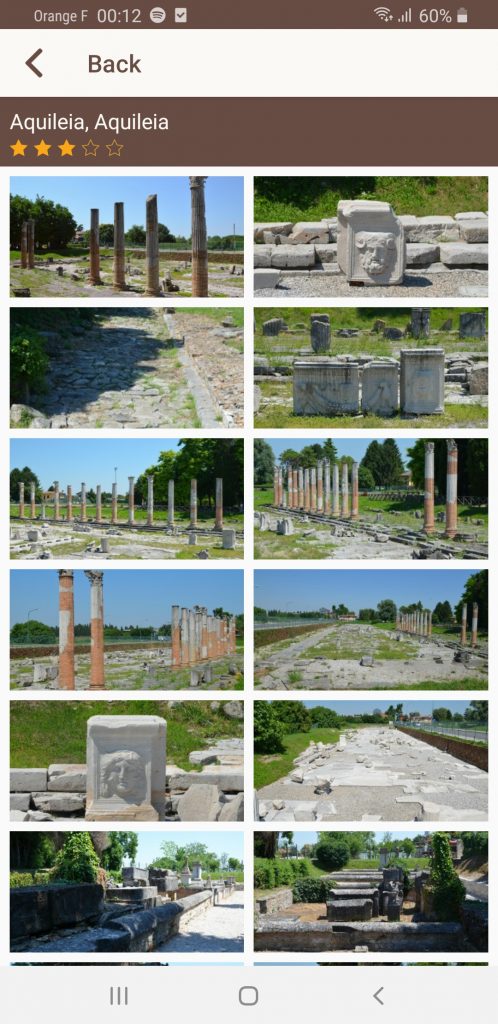

What to See in Aquileia now ?

Aquileia is rich with artifacts both found and in situ – indeed, some consider Aquileia as one of the best preserved examples of a Roman city. Archaeological digs have uncovered large portions of the original footprint, revealing respective parts of the ancient port, a bath complex, and the street grid. Complementing these fragments is the massive collection of antiquities in the National Archaeological Museum (Via Roma 1).

Aquileia on Timetravelrome App:

Author: Marian Vermeulen for Timetravelrome

Header image: Maximinus I, Sestertius. Minted 236-237. Obverse: Laureate, draped and cuirassed bust r. Reverse: Pax standing facing, head l., holding branch and sceptre. Source: Numismatica Ars Classica. Auction 98, lot 1332. Used by Permission of NAC.