“Then ensued a most disgraceful business and one unworthy of Rome. For, just as if it had been in some market or auction-room, both the City and its entire empire were auctioned off. The sellers were the ones who had slain their emperor, and the would‑be buyers vied to outbid each other.”

– Cassius Dio

Successful Career

As the son of a prominent noble family, Didius Julianus enjoyed opportunities that his predecessor, Pertinax, was forced to earn. He was raised in the home of Marcus Aurelius’s mother, Domitia Lucilla, and so received the support both of Domitia and of Marcus himself. He was made quaestor a year before the official legal age, and then later appointed aedile and then praetor. After commanding the Legio XXII Primigenia in Germania, he was given governorship of Gallia Belgica, which he administered well, including holding out against an attack by the Chauci tribe of Germania. He also served several other offices under Marcus Aurelius, and attained the position of consul.

Didius almost lost his life after Commodus succeeded his father as emperor. For while he was serving as superintendent of money grants to the poor of Italy, a soldier named Severus Clarissimus accused him of being in league with Salvius in his plot to kill the emperor. Commodus treated most perceived threats to his reign with brutality, but in this case he had already killed so many prominent noblemen that he feared he would soon cross the line and earn the opposition of the people, so he instead pardoned Didius, executed Severus Clarissimus, and gave Didius governorship of Bithynia. He became consul for the second time, and served it with Pertinax.

An Empire is Auctioned

At the time of Pertinax’s murder, Titus Flavius Claudius Sulpicianus, the father-in-law of Pertinax who was serving as consul, was in the Praetorian camp attempting to keep order. Some Praetorians began to suggest that Sulpicianus be named emperor, but Didius Julianus, hearing of the death of Pertinax, was eager to make his own attempt for the throne. Standing outside the gates of the camp, he started offering the soldiers sums of money if they would make him emperor. As a result, a fierce bidding war began between Sulpicianus and Julianus, as the Praetorians essentially sold Rome to the highest offer.

In the end, it was Didius Julianus who made the winning proposal, raising his bid by 5000 sesterces per soldier all at once, shocking the Praetorians and at the same time insinuating that Sulpicianus would seek to avenge the death of Pertinax. They threw their support behind Julianus at a price of 25,000 sesterces each. Escorted by the Praetorians, Julianus made his way to the Senate house to demand that they appoint him emperor. He gave an excellent speech in his own defense, but his claims of coming humbly before them alone to plead his case were undermined by his escort of Praetorians, who surrounded the Senate chambers and many had even joined him inside. Although the Senators feared and hated him, they were cowed into agreement, and made Julianus emperor.

Uneasy Ascension

Upon receiving imperial power from the Senate, Julianus went up to the palace. Pertinax’s dinner was still on the table. Julianus mocked the simple meal, and then sent out for expensive food for himself and his supporters. With Pertinax’s decapitated body still lying unattended in the building, they feasted and played dice late into the night. The Historia Augusta says that after this incident, Julianus did at least see to a proper burial for Pertinax, but he never spoke of him again and the Senators were too frightened to mention his name.

The people of Rome, however, were not nearly so cautious. They “went about openly with sullen looks, spoke their mind as much as they pleased, and were getting ready to do anything they could.” It all came to a head when Julianus prepared to make a sacrifice to Janus in the forum. The people began to shout at him, accusing him of parricide and stealing the empire. In an attempt to silence them, Julianus offered them money. Rather than calming the crowd, it only enflamed them more that he believed they could be bought, and they cried “We don’t want it! We won’t take it!”

Julianus finally lost his temper and ordered the Praetorians to kill those standing closest to him. Even this did not silence the angry populace, “and it did not cease expressing its regret for Pertinax and abusing Julianus, invoking the gods and cursing the soldiers; but though many were wounded and killed in many parts of the city, they continued to resist.”

Pretense and Preparations

Having taken power through bribery, intimidation, and violence, Julianus now attempted to change his tune. He paid respects to the Senate, gave favors and banquets, and tried to court their support. He even tried to appear humble before them, for when the Senators voted to make a gold statue of him, he refused it, saying “Give me a bronze one, so that it may last; for I observe that the gold and silver statues of the emperors that ruled before me have been destroyed, whereas the bronze ones remain.” Cassius Dio noted that “he was mistaken, for it is virtue that preserves the memory of rulers; and in fact the bronze statue that was granted him was destroyed after his own overthrow.” Yet despite Julianus’s best efforts, the Senate remained sullen and suspicious, considering his actions to be ingenuous flattery.

In the meantime, rebellious elements were stirring in the Legions posted around the Empire. The most competent was Septimius Severus, governor of Pannonia. His soldiers declared him emperor, and he began to plan a march on Rome. Julianus compelled the Senate to name Severus as an enemy of the state, and attempted to send assassins to get rid of his rival, but they were unsuccessful. Concerned over the incoming enemy, Julianus made efforts to prepare a defense, much to the amusement of the still disgruntled Senate and people, for the Praetorians and local navy were soft from lack of action, and even the elephants threw their riders.

The end of Julianus

When Severus had reached Italy, and taken Ravenna without a fight, the Praetorians themselves grew frightened of the war hardened veterans marching their way. The men that Julianus sent to disrupt the ranks or murder Severus kept deserting and joining his soldiers, and they were exhausted from drilling and preparation, all of which seemed fruitless. Into this atmosphere, Severus sent a letter promising the Praetorians that if they surrendered the murderers of Pertinax, no further action would be taken against them. The Praetorians resolved to support Severus, and when the Senate learned of their decision, they sentenced Julianus to death as an enemy of Rome and voted to appoint Severus as emperor.

The Praetorians came upon him while he was reclining at the palace and killed him just as they had Pertinax – he had ruled for only two months and five days. His body was delivered to his wife and daughter and laid to rest in the family tomb on the Labican Way, and Septimius Severus became the next emperor of Rome, establishing the Severan Dynasty which ruled for the following four decades.

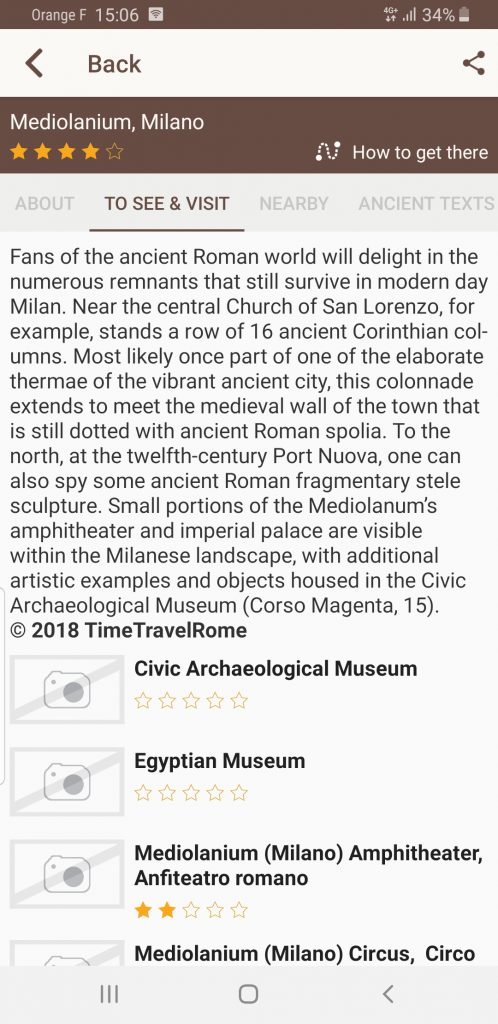

What to See in Roman Milan now ?

Fans of the ancient Roman world will delight in the numerous remnants that still survive in modern day Milan. Near the central Church of San Lorenzo, for example, stands a row of 16 ancient Corinthian columns. Most likely once part of one of the elaborate thermae of the vibrant ancient city, this colonnade extends to meet the medieval wall of the town that is still dotted with ancient Roman spolia. To the north, at the twelfth-century Port Nuova, one can also spy some ancient Roman fragmentary stele sculpture. Small portions of the Mediolanum’s amphitheater and imperial palace are visible within the Milanese landscape, with additional artistic examples and objects housed in the Civic Archaeological Museum.

It is possible for visitors to view the foundations of several small buildings from the civilian settlement, probably the residences of soldier’s families. These were discovered whilst excavating in the Michaelerplatz and have been left on permanent display. Although it is not possible to view much of Vienna’s Roman archaeology in situ, there are several museums with excellent Roman collections. These include the Wien Museum and the Romermuseum, which includes the remnants of two tribunes’s houses amongst its collection.

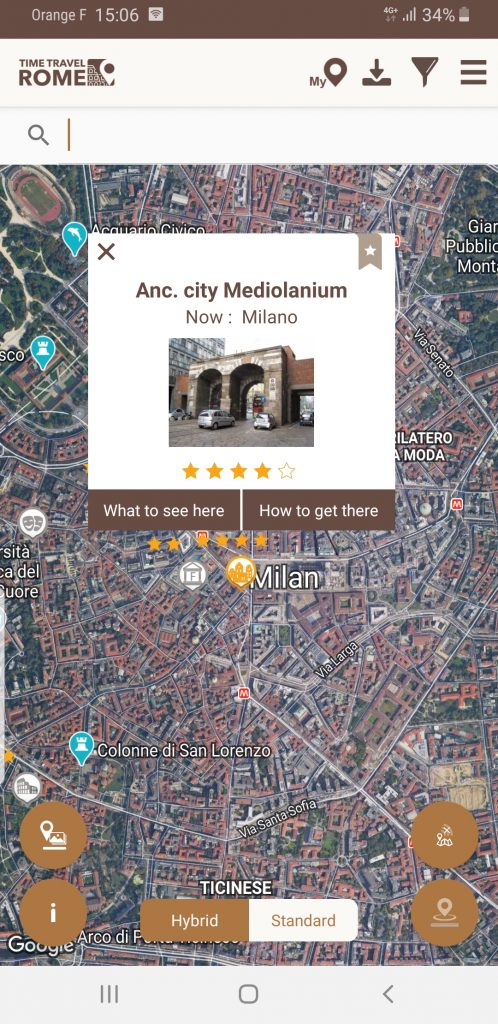

Milan on Timetravelrome App:

Author: Marian Vermeulen for Timetravelrome

Sources: Historia Augusta, Didius Julianus; Cassius Dio, Roman History

Header image: Bust of Didius Julianus in the Antiquarium (Münchner Residenz), photo by Sailko, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.