No, not the desperate Spartan defense of the pass against the Persians, made famous by big muscles and lots of slow motion in the movie 300. In fact, over the centuries, many Battles of Thermopylae have taken place in that mountain pass. However, today the terrain has changed. Visitors no longer see the narrow passage of ancient times, but an open plain. The Romans took part in the Battle of Thermopylae of 191 B.C., in their first engagement with King Antiochus of the Seleucid Empire. Like the Spartans, the Seleucids found that Thermopylae did not provide them as strong of a tactical advantage as they had hoped.

Move to Thermopylae

Antiochus III was the sixth ruler of the Seleucid Empire. While his predecessors had shown no great flair for conquest, Antiochus was a reflection of the first great ruler of the empire, Seleucus I Nicator. After successfully retaking Coele-Syria from the Ptolemies, Antiochus turned his attention to Greece. Philip V of Macedonia had recently lost the Second Macedonian War with Rome. Frustrated and forced to pay indemnities to Rome, Philip was a prospective ally. Although the Roman Senate made a great show of declaring Greece free, they had left several garrisons in key cities. So when the Aetolian League invited Antiochus to invade and deliver Greece, the Seleucid King was eager to accept. Despite the advice of the exiled Carthaginian general Hannibal, taking refuge at the Seleucid court, Antiochus moved quickly into Greece. He expected that the Grecian city-states would flock to his cause.

Antiochos III ‘the Great’. 223-187 BC. Very rare gold Oktadrachm (34.00 g). Seleukeia on the Tigris mint. Struck circa 211/0 BC. One such coin is also held in Altes Museum Berlin. As per CNG notice: “The powerful portrait, quite distinct from the established manner at Seleucia, must represent a special commission and should therefore reflect the king’s appearance c. 210”. Source: Classical Numismatic Group, www.cngcoins.com, used by permission of CNG.

Antiochus enjoyed some early success. He took the city of Chalcis from the Roman garrison, marrying a young girl that he fell in love with and spending the winter there feasting and resting. Yet as he moved out of the city in the spring, he found himself outnumbered. Rome had sent 20,000 infantry, 2,000 cavalry, and 15 war elephants under the command of Manius Acilius Glabrio. Additionally, all besides the Aetolian League either remained neutral or joined the Romans, even Philip. Antiochus decided to position his army defensively in the gap at Thermopylae. Following in the footsteps of the Spartans, he hoped that the bottleneck of the pass would decrease the advantage of the enemy’s superior numbers.

New Battle Tactics

However, he also knew his history. For when the three hundred Spartans and their Greek allies had defended the pass, they were overcome after the Persians learned of a small footpath that allowed them to flank the Greek forces. Aware of this, Antiochus ordered the small detachment of Aetolian soldiers, currently stationed in Heraclea, to guard the footpath. Unfortunately, only about 2,000 of them followed his commands. The rest decided to remain safely in Heraclea and await the outcome of the battle.

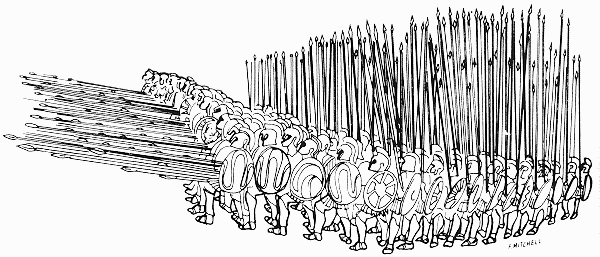

Manius brought his forces up, and the two sides clashed in pitched battle. Initially, Antiochus and his army fared well, but the Roman army was a dangerous opponent. The Seleucid Empire was one of the kingdoms formed by a former general of Alexander the Great. The army subsequently fought in the deadly sarissa phalanx that had made the Macedonians the conquerors of the world. The phalanx was a formidable barrier, but only in a solid formation and in a single direction. In close, hand-to-hand combat, it was far less effective.

In contrast to this, the Roman army enabled both styles. Polybius explained how “the order of battle used by the Roman Army is very difficult to break through, since it allows every man to fight both individually and collectively; the effect is to offer a formation that can present a front in any direction, since the maniples that are nearest to the point where danger threatens wheel in order to meet it.” Additionally, the Roman generals remained out of direct action in the battle, allowing them to direct their several ranks and keep a flow of fresh soldiers entering the fray against their fatigued enemies.

Antiochus Defeated

In that infamous pass at Thermopylae, the Roman Army slowly wore down the main body of the Seleucids. Meanwhile Manius, who was equally familiar with the battlefield’s history, sent his two two senior legates, Lucius Valerius Flaccus and Marcus Porcius Cato, to the old footpath. Though Flaccus’s forces fell back, Cato’s dislodged the token force of Aetolians defending the secret route. Like the Persians before them, they circled around the Seleucid lines and attacked from the rear. As a result, the phalanx shattered, and the men fled in a panic. According to the ancient sources, 10,000 Seleucids died in the battle, with a loss of only 200 Romans. Antiochus withdrew from Greece with what remained of his men.

The following year, a Seleucid fleet commanded by Hannibal suffered a crushing defeat. Following some skirmishes in Asia Minor, the land armies met for a final, definitive battle at Magnesia. There, Antiochus and the Seleucids faced off against a coalition force of Romans and their allies from Pergamon. The Roman commander was Lucius Cornelius Scipio, the younger brother of the famous Scipio Africanus, who was himself serving as his brother’s second-in-command. The battle was a decisive victory for Rome. Antiochus was subsequently forced to withdraw from much of Asia Minor and negotiate a peace that left him heavily in debt. Rome gained further control of Greece, and her allies received the former Seleucid territories in Asia Minor.

What to see in Thermopylae now :

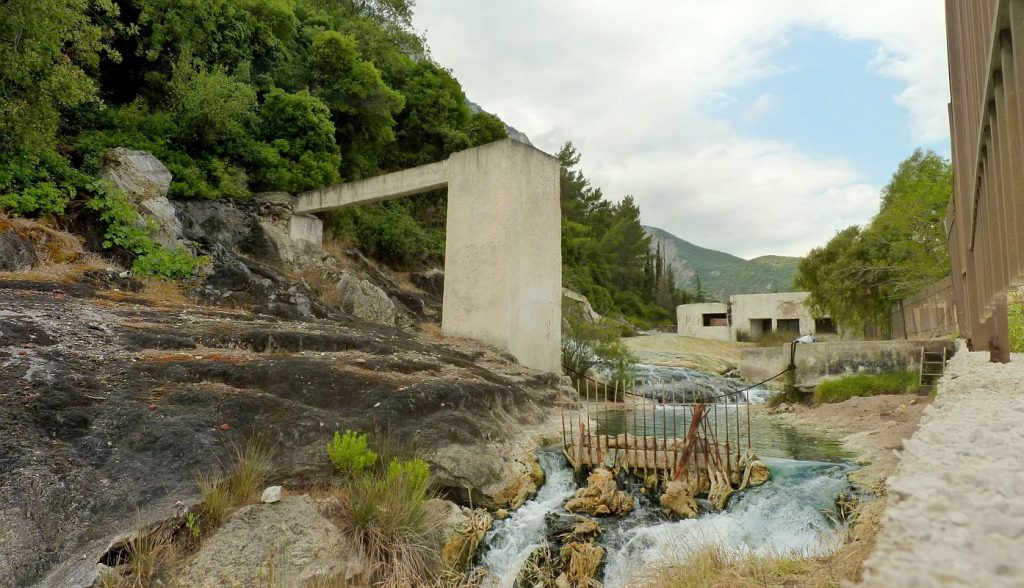

Extensive silting has dramatically altered the layout of the area, so much so that the once formidable “Hot Gates” would now make for fairly easy passage for an invading army. Archaeologists have uncovered some burials, along with a number of Persian artefacts such as bronze arrowheads. Of the sanctuary, only the traces of a few monuments have been uncovered, including of a stoa and a stadium. Of interest in the stadium there is the unusual construction at the western end of the stadium, which is believed to have been designed to keep the winter rains from washing out the floor.

Thermopylae on Timetravelrome app:

To find out more: Timetravelrome.

Author: written for Timetravelrome by Marian Vermeulen.

Sources: Appian, The Syrian Wars; Livy, History of Rome.

Header Photo: Antiochos III ‘the Great’. 222-187 BC. AR Tetradrachm (29mm, 16.96 g, 12h). Antioch on the Orontes mint. Struck circa 204-197 BC.

Source: Classical Numismatic Group, www.cngcoins.com, used by permission of CNG.