In the late to mid-40s A.D. Sarmizegetusa became the capital of Dacia under King Burebista. Perhaps the word fortress is more apt for the site. It consisted of six citadels, constructed on the top of a 1200 meter high mountain. The main fort lay on five terraces at the peak of the mountain. Civilian lodging spread across further systems of terraces below. It reached its height of success under the Dacian King Decebalus, who engaged in multiple wars with the Romans. In his final conflict with the Emperor Trajan, Decebalus resorted to subterfuge in a last, desperate attempt at victory.

First Dacian Wars

Decebalus was a shrewd general, and he had won success against the Romans in earlier wars. In the First Dacian War, Emperor Domitian claimed victory far too soon. While he was back in Rome celebrating his triumph, Decebalus was defeating the Roman legions left in Dacia. Revolts in other areas of the Empire kept Domitian from being able to return to the war. Instead, he shamefully accepted Dacian terms for peace. He hailed Decebalus as king, and agreed to pay an annual tribute to him to maintain peaceful relations.

Domitian’s successor as emperor was the well-beloved Trajan. A sharp administrator and a skilled general, Trajan did not accept the tribute so mildly. In 101 A.D., he crossed the Danube River and invaded Dacia. Decebalus tried to request to meet with him, but Trajan refused. He pushed back the Dacian forces to the capital at Sarmizegetusa, destroying much of the city’s outer walls. Eventually Decebalus yielded and accepted Roman terms for peace. Yet the Dacian king was not as passive and subdued as he appeared. He re-fortified his cities and then launched an attack on Roman held territory. Trajan came at once to inspect the Roman forts and take personal leadership of the war.

Decebalus’s Subterfuge

Knowing the quality of his enemy, Decebalus struck in guerilla attacks. He also formed a plan to assassinate Trajan, but the plot was discovered. Next, he sent a carefully crafted letter to Trajan’s general Gnaeus Pompeius Longinus, swearing that he wished peace and promising to submit to anything the Romans asked of him. Though the Romans under Trajan had won their first conflict with Dacia, it had not been an easy one. This promised to be another bloody war, one which would cost many more lives. The prospect of peace and the preservation of his men proved too tempting for Longinus.

He agreed to meet, but when he came to Decebalus, the Dacian king took him prisoner, and proceeded to question him publicly, trying to learn of Trajan’s plans. Though interrogated for hours without respite, Longinus refused to give up any information. Decebalus eventually realized it was useless. Instead, he sent an envoy to Trajan, informing him of his prisoner. He demanded that, in exchange for Longinus, Trajan must return all territory and pay all the costs incurred by the Dacians in defending against the Rome. Trajan was distraught at the message. He could not give in to the demands, but also could not bear to sacrifice his dear friend. Desperate, he responded with a carefully ambiguous letter, hoping to protect Longinus while stalling for time.

Ion Popescu-Băjenaru / Institutul de Arte Grafice Carol Göbl, 1914, picture in public domain.

The Scheme Fails

It worked, and Decebalus was still debating his next move when Longinus took matters into his own hands. He could not bear laying the guilt of his death on the head of his friend and Emperor, nor did he wish any dishonorable terms to be named in his release. His freedman, taken captive with him, managed to obtain a small vial of poison. Longinus also wished to secure the safety of his freedman, so he sent for Decebalus and told him that he would convince Trajan to ransom him. He wrote a letter, begging for his freedom, and Decebalus allowed Longinus’s freedman to deliver it to Trajan.

Thus assured that his man was safe, Longinus drank the poison and took his own life. Trajan was devastated when he received the note and heard the truth of Longinus’s plan from the freedman. Shortly thereafter, Decebalus sent over one of the captured Roman centurions, who informed them of Longinus’s death and gave a message from the Dacian king. He demanded the return of the freedman in exchange for Longinus’s body. However, Trajan, who highly valued the lives of his people, would not even send the centurion back and flatly refused to surrender the freedman. He believed the men’s safety to be more important for the dignity of the Empire than the burial of Longinus.

Trajan Conquers

Trajan pushed on to Sarmizegetuza. Though the Dacians repelled the first attack, the Romans lay siege to the city. As their siege engines maintained a constant barrage, the soldiers built a wall to circumvallate the city. Finally they destroyed the pipes bringing drinking water into the city, and threatened to burn the fortress down. The Dacians surrendered. This time, the Romans deported the citizens and destroyed the ancient capital. With the help of a defector, Trajan found Decebalus’s treasure, which the king had concealed under the Sergetia River. Decebalus escaped the siege, but killed himself to avoid capture and humiliation at the hands of the Romans. The events of the Dacian Wars can be seen carved onto Trajan’s column in Rome. Sarmizegetuza was never rebuilt, though the Romans founded their own new capital about 40 km away, and named it after the original.

Decebalus, king of the Dacians, dying by his own hand during his retreat after the Battle of Sarmizegetusa; A plaster-cast copy of the Trajan’s Column, as shown at the Museum of Romanian History in Bucharest, Romania. Picture by Halibutt , licensed under CC BY 3.0

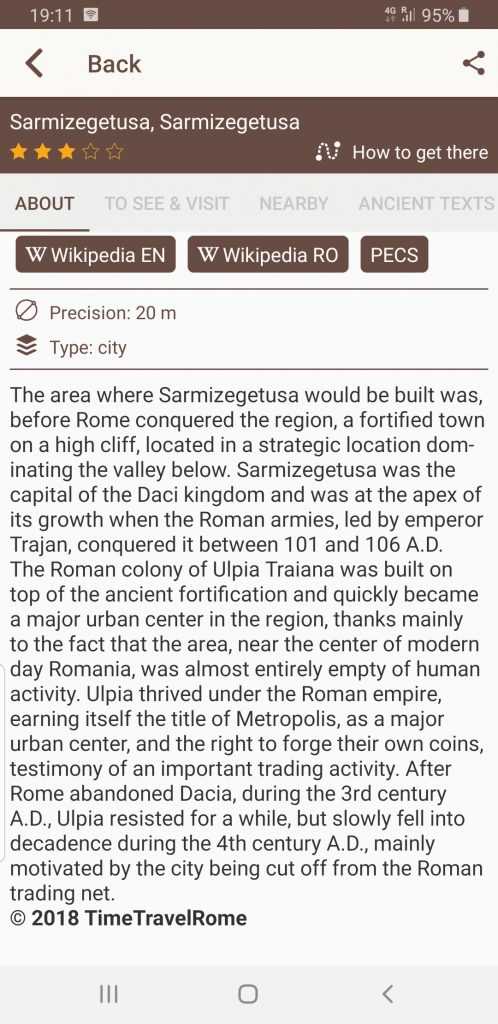

What to see in Sarmizegetusa today:

Ruins of both the Dacian fortress and the Roman city are in the area. However, recent nationalistic reasons have brought the first to receive far more attention than the other. The Dacian fortress has its own archeological park, open for visit and equipped with guided tours.

The Roman ruins are mainly pieces of damaged structures, but two areas of the ancient Forum remain on the outskirts of the modern town. Most classic civil structures are also still present. These include the foundations of an amphitheater, a granary and a number of temples.

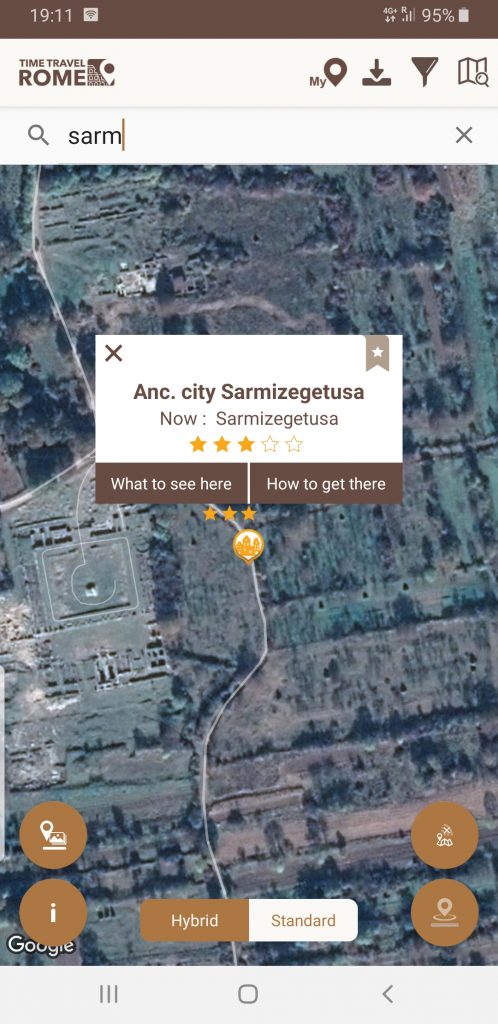

Sarmizegetuza on Timetravelrome app:

To find out more: Timetravelrome.

Author: written for Timetravelrome by Marian Vermeulen.

Sources: Cassius Dio, Roman History; Sextus Aurelius Victor, Epitome De Caesaribus; details recorded from Trajan’s Column

Header Photo: Aerial photographs of Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa by Raimond Spekking & Elke Wetzig licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0