Some travelers who come to Rome think that Trajan’s column was the very first of its kind and that it is unique. In reality, Romans have erected many great columns in Rome and across the Empire. Some of them still stand today, but most of them are unfortunately lost. We know about a dozen of Columns that stood in Rome, but only three of them are still standing today. Fortunately enough, three others “lost” columns were not lost entirely: they can be seen on ancient coins.

Three lost honorific columns on coins

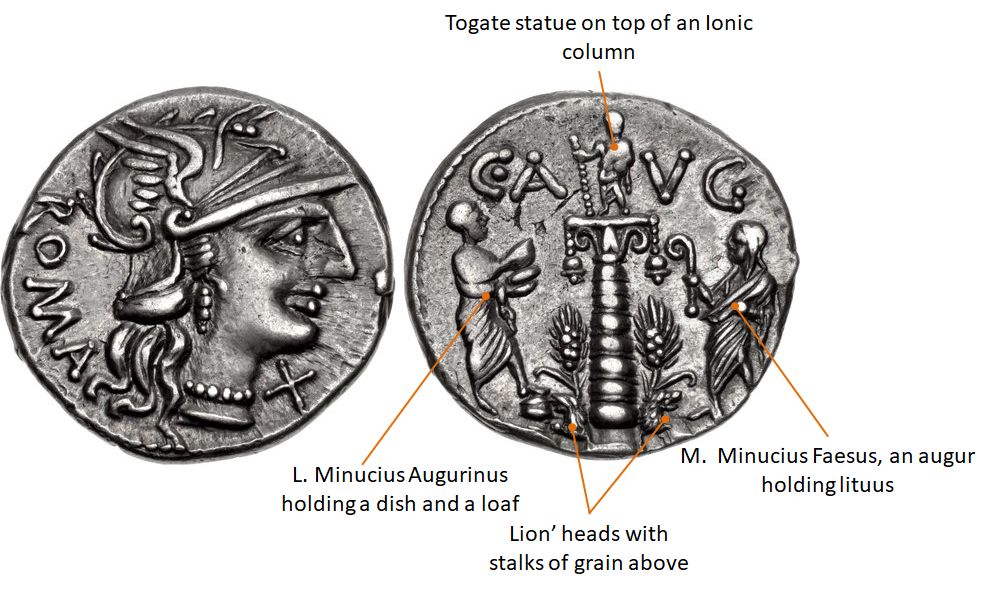

The first of columns that ever appeared on coins is Columna Minucia – it was also the first honorific column of Rome. It was erected in 439 BC on Comitium. Its construction was financed through a popular subscription to commemorate L. Minucius Augurinus, who was consul in 497 and in 491 BC. During his service, he consecrated the temple of Saturn on the Forum and Saturnalia festival took place for the first time. Also, he managed to deal with famine that struck Rome in 490 BC. The theme of salutary grain shipments from Sicily can be seen on the republican denarius struck by C. Augurinus in 135 BC in honor of his famous ancestor.

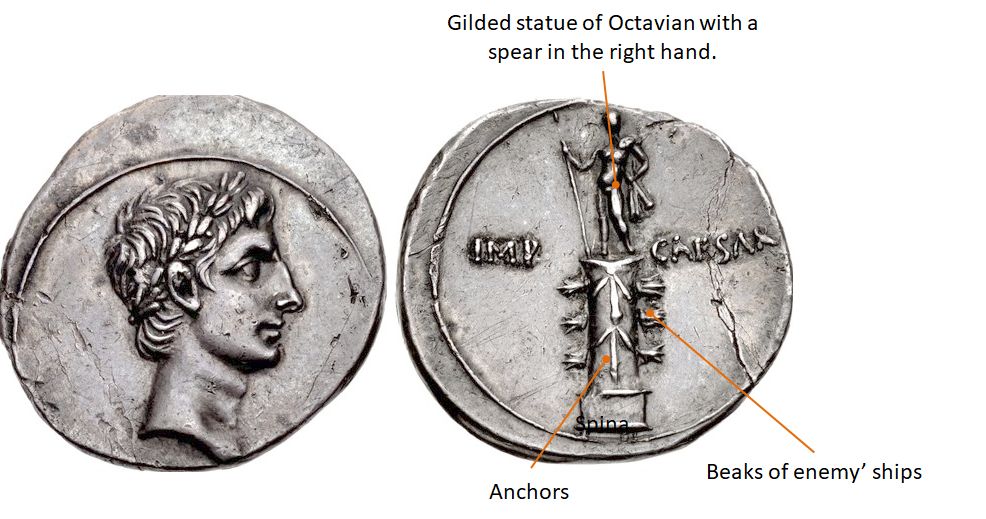

The second famous column of antiquity is Columna Rostrata Augusti. It was erected on the Forum in 36 BC by Octavian to commemorate its victory over Sextus Pompey, who was the last center of opposition to the Second Triumvirate. The victory over Sextus was hard to achieve and Octvian spared to no means to commemorate it. This column stood between the Forum’ Rostra and the spring on the Forum called Lacus Curtius. It is likely that the entire column was built from melted beaks of enemy’s ships. Its was possibly gilded, as well as Octavian’s statue that was placed on top of it.

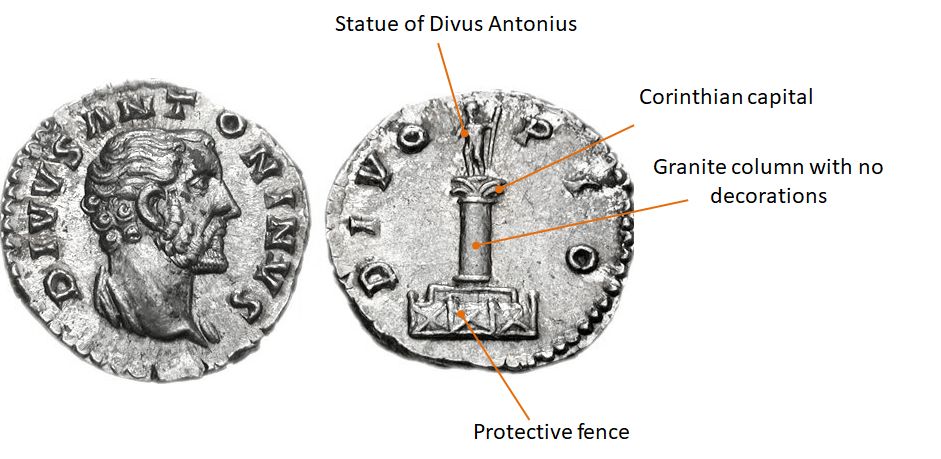

The third column preserved on coins is the Columna Antonini Pii – the column of Antoninus Pius. It was built by emperors Marcus Aurelius and Licius Verus in the memory of Fausina and Antoninus Pius. This column stood on Campus Martius not far from the column of Marcus Aurelius (the latter is still standing today). The column was made of a monolithic slab of red granite and had a decorated base of white marble. The column survived until modern times, but it was damaged by fire in 18th century. Its granite broken pieces were recycled for the restauration of the obelisk of Augustus that stands now on the Piazza Monte Citorio. Only the base of the column was preserved: it has a dedicatory inscription on one side and reliefs on three others. One of three relief of the basement depicts Faustina and Antonius carried by a genius on its wings. Two other reliefs show the Decursio Equitum – a procession that was held before the funeral pyre was lit. The depiction of the base, which was heavily restored, can be seen here.

Columna Traiana: The most spectacular one

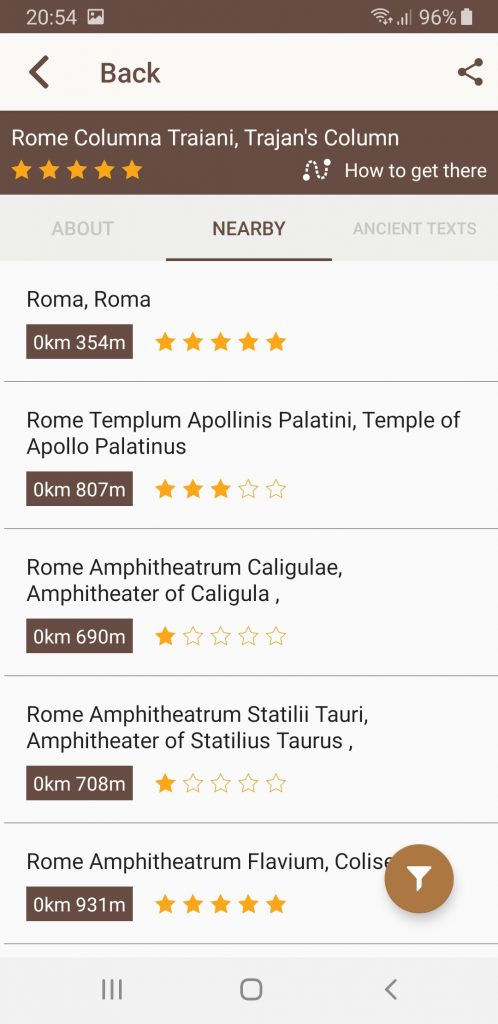

Three ancient columns still stand today in Rome: the column of Trajan (called Columna Traiana), the Column of Marcus Aurelius (its whole name is “Columna Centenaria Divorum Marci et Faustinae”) and the column of Phocas. The latter is also called the Columna Focae – it was erected in 608 AD by Smaragdus, exarch of Italy. But the most spectacular of the three columns of Rome is certainly the Column of Trajan.

The Column of Trajan was dedicated to Trajan war in Dacia. Between 101 – 102 and 105 – 107 AD, the Emperor Trajan waged a war in the territory that is now Romania and Transylvania, partly to contain the Dacian threat, partly to incorporate their natural resources, and partly to avenge an earlier humiliating defeat that Rome had suffered under Domitian. Rome inevitably triumphed. And doing what a Roman emperor did best, Trajan decided to monumentalise Rome’s victory by literally setting it in stone (or rather marble) on a 30 metre-tall victory column.

As well as a commemorative monument gloating over a barbarian defeat, Trajan’s Column also doubled up as the emperor’s sepulchre. This was pretty controversial. Burial within the city limits was a rare privilege, and with him being the modest man that he was, we can assume that Trajan wouldn’t have presumed this privilege for himself—even if the Senate did vote him Optimus Princeps (or “best ruler”). But he hedged his bets by having a tomb built within his column’s base. And he guessed right, his ashes deposited sub column in a golden urn late in the sweltering summer of 117 AD.

First we advanced to Berzobim…

Trajan’s Column is most famous for portraying scenes from the emperor’s Dacian campaigns on its spiralling frieze. It shows a staggering 155 stages of the war (Trajan appearing in 58 of them) and would have stood between two libraries containing his dispatches from the frontline. Indeed, Trajan actually wrote a commentary about the war—probably in the style of Caesar’s Bellum Gallicum—in a work known as the Dacica. Only five words of it have survived, however—the deeply moving lines inde Berzobim, deinde Aizi processimus roughly translating as, “first we advanced to Berzobim, then we moved on to Aizi.”

Curiously enough, few of the column’s scenes are violent. Depictions of battle feature far less than those of travel, sacrifice, adlocutio (divine summoning) and submissio (the enemy’s submission). So why, on a monument commemorating military victory, would its designers have decided to tone down the bloodshed? The answer probably lies with the fact that around the time of the column’s completion in 113 Trajan was already planning another campaign in Parthia.

The Pathian campaign would prove far more costly than the campaigns in Dacia and reap far fewer rewards: undertaken principally to enhance Trajan’s prestige as a good old-fashioned military imperator. The decision to represent the Romans as being so militarily superior that their enemies would readily submit was therefore a propagandistic one intended to get the populace on board. Understandably, it was a far better alternative to depicting the harsh realities of attritional warfare which in reality they would have to fight.

A story that was impossible to read?

As impressive as the column is, scholars have long scratched their heads trying to work out how contemporaries would have been able to piece together its narrative without walking round and round in circles and severely cricking their necks. And that’s when its frieze was still polychrome! You could certainly once get an elevated view of the column from the Basilica Ulpia’s first-floor terrace. But given that this terrace didn’t spiral around the monument, it could quite literally only give you one side of the story.

Ultimately we don’t know. It could simply be that the architect’s blind vision got in the way of the monument’s practicalities. What’s beyond doubt is the magnificence of the column itself: within the monument is a spiralling staircase, at the base of the column is a dedicatory inscription from the Senate and the People of Rome, and once standing atop the column was a bronze statue of the emperor. But it has long since been lost; stolen along with the earthly remains of the emperor which were looted in the Middle Ages.

Author: Alexander Meddings with additions and edits by TTR.

Source of header pic – please see sources of coins mentioned in the article above.

To find out more: Timetravelrome.